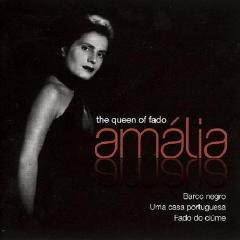

Amalia Rodrigues - The queen of fado (2011)

Amalia Rodrigues - The queen of fado (2011)

01. Barco Negro 02. Nao Digas Mal Dele 03. Uma Casa Portuguesa 04. Novo fado da Severa 05. Perseguicao 06. Duas luzes 07. Faz hoje um ano 08. Passei Por Vocк 09. Fado do ciume 10. Sei finalmente 11. As penas 12. A tendinha 13. Fado Amalia

When Amalia Rodrigues died October 6th, 1999 (aged 79) the government of Portugal declared three days of national morning. Political activity in the country's general election campaign came to a halt. The president was the chief mourner at the singer's state funeral. It was a singular expression of national grief and in some ways a peculiar one.

Entertainers, however famous, rarely, if ever, depart in such ceremony. It did not happen to Maria Callas, perhaps the most celebrated opera singer of recent times, when she died in 1977; or to Frank Sinatra, who died in 1998. There was some sadness, certainly; a lot of reminiscences, of course; but life went on largely uninterrupted in Greece and America. The sanctifying of Amalia Rodrigues may say something about the nature of the Portuguese as well as about what the prime minister called “the voice of the country's soul”.

She was known simply as Amalia. The diminution of her name was itself a reflection of her fame (as was Britain's Diana, or Di, whose death in 1997 also briefly interrupted the life of her country). Her style of singing is called fado, the Portuguese word for fate. “I have so much sadness in me,” Amalia said. “I am a pessimist, a nihilist. Everything that fado demands in a singer I have in me.” Amalia's message of fatalism seems to have echoed a mood among her admirers. Portugal is still among the least modern of European countries, though it has been modernising rapidly of late. It expects its economy to grow by about 3% this year, compared with an average of only 1.9% growth for the rest of the euro area. But GDP does not change a country's sentiment overnight. Portugal was the first European country in modern times to carve out a great trading empire. Go almost anywhere in the world and you find traces of Portuguese architecture, language and genes. Generation by generation, the once-rich Portuguese have seen their empire slowly vanish, and not very gracefully. East Timor is still formally Portuguese. “I sing of tragedy,” Amalia said, “of things past.”

Amalia Rodrigues was never sure of her exact birthday. Her grandmother said it was in the cherry season, so she assumed she was born in early summer. Other details of her childhood were also obscure. Some accounts said her father was a shoemaker; others that he was a musician. The story that as a teenager she sold fruit on the docks of Lisbon, capturing the hearts of her customers with her singing, was willingly believed by those who adored her. The adoration was put to the test in 1974 when Portugal emerged from half a century of dictatorship. Amalia's critics said she had benefited from the patronage of the most enduring of Europe's fascist regimes.

“I always sang fado without thinking of politics,” Amalia responded angrily. It was a claim impossible to contradict. Yet fado, with its melancholy fatalism, was an appropriate accompaniment to the thinking of the Portuguese leader, António de Oliveira Salazar. Not for him the ruthless urgency of Hitler. Rather, in his corporate state he wanted to preserve Portugal as a rural and religious society where industrialisation and other modernising influences would be excluded. He kept Portugal out of the second world war. It was too wearisome.

Fado was the music of Portuguese tradition. If it had any foreign ingredients they were from Africa, but these were acceptable: huge areas of Africa had been Portuguese. And here was Amalia, the queen of fado, clad all in black, her throbbing voice accompanied by two guitarists, her head thrown back, her eyes closed. She was the essence of sadness, bearing the memories of two marriages; both unhappy. When Salazar heard “O Grito” (“The Cry”) he allowed himself a tear.

Unsurprisingly, the Portugal that followed the dictatorship wanted cheering up, as well as modernising. The question of whether Amalia had been a supporter of the old regime became irrelevant. Fado itself fell out of fashion. Rock was the music of democracy.

Amalia, however, had built up other audiences abroad. The Brazilians, whose language is Portuguese, flocked to see her dozen or so films. A six-week tour to Rio and other cities had to be expanded to three months. In the United States record collectors said that her songs, with their four-line stanzas, were like the blues, and she did indeed make some recordings with a jazz saxophonist, Don Byas. Italians claimed to see links between fado and opera. The French said Amalia reminded them of Edith Piaf, who sang nostalgically of the tragedies in her life. A fado song given the English title “April in Portugal” became a hit in several countries.

In Portugal fado and Amalia gradually made a comeback. Amalia showed that she was really a democrat at heart by recording “Grandola Vila Morena”, the song that had swept the country when the dictatorship ended. The socialist government presented her with the country's highest decoration, the Order of Santiago. She was giving concerts up to a year ago, and every one was sold out. “The sadder the song, the more the Portuguese like it,” she said. In this new time of change, pessimism was back in fashion. For Amalia, it was the happiest of endings. --- economist.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega zalivalka cloudmailru oboom

Zmieniony (Czwartek, 02 Lipiec 2015 08:53)