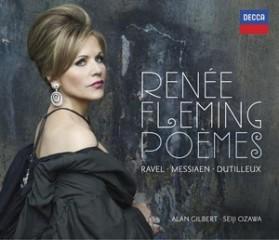

Renée Fleming – Poèmes (2012)

Renée Fleming – Poèmes (2012)

MAURICE RAVEL (1875–1937) Shéhérazade 01 I Asie 11:02 02 II La Flûte enchantée 03:32 03 III L’Indifférent 04:14 OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908–1992) Poèmes pour Mi (with orchestra) Premier Livre 04 I Action de grâces 05:58 05 II Paysage 02:00 06 III La Maison 01:55 07 IV Epouvante 02:53 Deuxième Livre 08 V L’Épouse 03:00 09 VI Ta voix 03:15 10 VII Les Deux Guerriers 01:40 11 VIII Le Collier 04:21 12 IX Prière exaucée 03:11 HENRI DUTILLEUX b.1916 Deux Sonnets de Jean Cassou 13 I II n’y avait que des troncs déchirés 02:19 14 II J’ai rêvé que je vous portais entre mes bras 05:30 Le Temps l’horloge* 15 Le Temps l’horloge 01:43 16 Le Masque 04:25 17 Le Dernier Poème 02:06 18 Interlude 01:20 19 Enivrez-vous 04:39 Renée Fleming - soprano Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France Alan Gilbert - conductor Orchestre National de France Seiji Ozawa – conductor

All singing is a kind of story telling, and René́e Fleming, whose vast repertoire includes many works demonstrating the breadth and richness of the French tradition, is no stranger to the particular skills required of the art. Scheherazade, as she is usually spelt in English, was the teller of the Tales of the Arabian Nights, whose prowess at inventing stories enabled her to survive a Sultan’s cruel decree for 1001 nights— and thereafter, presumably, live happily ever after. In 1888, the Russian composer Rimsky-Korsakov wrote a colourful orchestral suite celebrating her and some of her stories, which Maurice Ravel would certainly have known when, in 1898, he began an opera about her. Nothing seems to survive of that unfinished work apart from the overture, which is entirely separate from the group of three orchestral songs the composer wrote five years later.

Ravel’s Shéhérazade dates from his early maturity and its lush yet subtle harmony and refined if occasionally overwhelming orchestration are typical of the magic this delicate human being could create with his powerful art. They are settings of a poet whose real name was Léon Leclère (1874–1966), but whose pen name, which combined the hero of one of Wagner’s operas with the villain of another, was Tristan Klingsor.

The cycle was first performed in Paris in May 1904. The first song conjures up a vision of Asia, an Asia of the imagination drawn from picture books and fairy tales and including mystery, violence, beauty, eroticism, and a variety of perfumed scenes from Syria, Persia, India and China as if visited on a flying carpet. The second, La Flûte enchantée, begins with the tones of the instrument. The singer is listening to it from inside a house where her master is asleep. She is a servant, and her lover, outside, plays the flute. In the final song, L’Indiffé́rent, a young man of ambivalent sexuality strolls attractively by a house from where the singer watches and invites him in. But he merely passes on, with a graceful gesture.

Olivier Messiaen composed Poèmes pour Mi for his first wife, the violinist and composer Claire Delbos. They had met at the Paris Conservatoire, where both were students, and soon they were giving recitals together. They married on St Cecilia’s Day (22 November) 1932. “Mi” was the composer’s pet name for his wife. Messiaen went on to compose, in 1936, this cycle of nine songs to his own texts — both intimately personal and religious — celebrating their happiness. They were originally for voice and piano; he created an orchestral version the following year. With its immediacy and blend of simplicity with voluptuousness, the cycle has become one of his most performed works.

Tragically, towards the end of the Second World War, Mme Messiaen’s health declined. Following an operation she lost her memory and was hospitalised, remaining in institutions until her death in 1959. Together with the Chants de terre et de ciel (1938), which also celebrates the Messiaens’ son Pascal, the Poèmes remain as a moving testimony to the short-lived happiness of the composer’s first marriage.

Messiaen himself died in 1992 at the age of eighty-three. His colleague Henri Dutilleux, eight years his junior, is fortunately still with us. His relatively small output is of consistent quality and imagination, as audiences both in France and elsewhere are increasingly appreciating. The recipient, especially in recent years, of several major awards — notably the Ernst Siemens Prize (2005), the Prix Midem (2007), an honorary fellowship from Cardiff University and the Gold Medal of London’s Royal Philharmonic Society (both 2008) — Dutilleux is now attracting the widespread attention he has so long merited.

He too studied at the Paris Conservatoire and later taught there, also enjoying an important professional relationship as Head of Music Production for French Radio from the end of the war until 1963. A member of no school, and not tied to any particular system of composition, Dutilleux has created a highly individual and distinguished œuvre, indebted to a degree to his forebears Debussy and Ravel, but also occasionally lightly shaded by the experience of jazz. A master of the orchestra, he has composed two symphonies as well as two major concertos — one for cello (written for Rostropovich) and one for violin (for Isaac Stern) — in addition to piano music and chamber works. Vocal music has figured infrequently in his output, but the small selection of his works for voice clearly demonstrates the high quality of his musical thought.

His first extant songs (Dutilleux has withdrawn some earlier examples) are the Deux Sonnets de Jean Cassou, composed in 1954 for voice and piano but later orchestrated. Cassou (1897–1986) was a museum curator who joined the French Resistance in 1940 when dismissed from his post by the Vichy government. His Thirty-Three Sonnets Composed in Secret (from which Dutilleux selects two) were created during his subsequent imprisonment, though not then written down as he was denied the means to do so; they were clandestinely published under the pseudonym Jean Noir in 1944 and their writer later received the Croix de Guerre.

Dutilleux returned to vocal composition for the important orchestral cycle Correspondances, premiered by Dawn Upshaw and the Berlin Philharmonic under Simon Rattle in 2003, and has more recently been inspired by the voice and artistic personality of Francophone soprano René́e Fleming to compose Le Temps l’horloge — four songs plus an interlude positioned between the last two (2006–09). The first performance of the complete cycle was given by Fleming at the Théâtre des Champs-É́lysées, Paris, with the Orchestre National de France under Seiji Ozawa, on 7 May 2009. The work employs a large orchestra with a couple of unusual additions — harpsichord and accordion — used with Dutilleux’s regular selectivity and subtlety.

His choice of poets is again characteristic. The first two songs — Le Temps l’horloge and Le Masque — set words by Jean Tardieu, a poet and musician alongside whom Dutilleux worked for many years at Radio France. Unusually, the interlude is also associated with a text — Tardieu’s prose poem Le Futur antérieur — though it does not set it. The text of Le Dernier Poème is by the Surrealist Robert Desnos, another member of the French Resistance, who died in the Nazi concentration camp at Terezín (Theresienstadt) in 1945. Finally, Dutilleux turns to his beloved Baudelaire, whom he cites as a major influence on his creativity and whose work also provided the title for his cello concerto, Tout un monde lointain. Enivrez-vous is one of Baudelaire’s posthumously published Petits Poèmes en prose, urging the necessity for a drunken (presumably meaning thoroughly uninhibited) approach to life in all its aspects. ---George Hall, deccaclassics.com

download: uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire solidfiles mega filecloudio nornar ziddu

Zmieniony (Poniedziałek, 07 Kwiecień 2014 08:47)