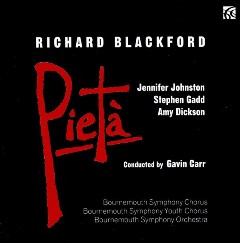

Richard Blackford - Pietà (2020)

Richard Blackford - Pietà (2020)

Pietà 1 I. Stabat Mater Dolorosa 4:43 2 II. Quis Es Homo 3:58 3 III. Pro Peccatis Suae Gentis 2:33 4 IV. Eia Mater, Fons Amoris 4:02 5 V. Sancta Mater, Istud Agas 3:49 6 VI. Weeks Fly Swiftly By 3:41 7 VII. A Chorus Of Angels Sang 3:58 8 VIII. Face Me Tecum Pie Flere 7:32 9 IX. Flammis Ne Urar Succensus 6:38 10 Canticle Of Winter (For Soprano Saxophone And String Orchestra) 6:27 Soprano Saxophone – Amy Dickson Mezzo-soprano Vocals – Jennifer Johnston Baritone Vocals - Stephen Gadd Bournemouth Symphony Chorus, Bournemouth Symphony Youth Chorus Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Conductor – Gavin Carr

Richard Blackford’s Pietà is a Stabat Mater, not with all of the 13th-century Latin text, but including a couple of settings of the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. The 40-minute piece is scored for mezzo and baritone soloists – both Jennifer Johnston and Stephen Gadd are powerfully expressive – plus the equally fine soprano saxophonist Amy Dickson, the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus and the strings of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, all capably led by Gavin Carr. Though Blackford’s musical ideas may possess little originality or individuality, everything he writes is skilful and effective, often with an emotional charge, as in the opening section. The uncertain, halting progress to the fifth movement, with its use of children’s chorus, is curiously touching; the saxophone obbligato, which throughout acts as a kind of counterpoint to the vocal soloists or to the chorus, gives the music heightened potency.

Even more successful is the atmospheric, six-minute Canticle of Winter, inspired by a Robert Frost poem, scored for saxophone and strings, which perfectly represents ‘the sense of restlessness, of something unresolved’ described by the composer in his programme note. ---classical-music.com

Five years ago, when reviewing Blackford’s Voices of Exile, I commented that in his socially committed choral works, while following in the model of such works as Britten’s War Requiem, the composer avoided the combination of religious texts with modern poetry which can lend such poignant irony to new compositions. Here, on the other hand, the situation is reversed, with two poems by Anna Akhmatova inserted into a predominantly liturgical setting of the Stabat mater – not with any ironic intention, but designed to highlight the meaning of the original text and render it more relevant to the modern listener. In his illuminating booklet note the composer says that he “wanted to grab the listener by the throat, to not let up on the intensity and drama of this incredible, timeless poem” - and to a very considerable extent he succeeds.

The opening section, consisting of four movements, is a comparatively conventional setting of the first ten verses of the sequence attributed to Jacopo da Todi (1230-1326), where Blackford allocates parts of the text to the various assembled forces: chorus, mezzo-soprano, baritone and soprano saxophone, which assumes an almost dramatic role as the consoling voice of angelic innocence. The third movement, for baritone solo, describes in harrowing terms the scourging of Jesus, and is fast and furious; the other movements are more contemplative, but nevertheless rise to impassioned climaxes and culminate in a sustained lament for the saxophone which brings this section to an end.

The three movements which make up Part Two are even more widely contrasted. Two verses are allocated to a children’s chorus which sings a deceptively innocent modal carol-like melody, and this is succeeded by the first of the Akhmatova settings, a real moment of anger for the mezzo-soprano experiencing the loss of her family and rising to a storming moment of fury on the words “threatening, swift and fatal, an enormous star.” This is succeeded by a four-minute movement scored for baritone and unaccompanied chorus, setting Akhmatova’s own contemplation of the Virgin at the Cross. Although this, too, rises to moments of emotion, the predominant impression is of extreme beauty and consolation. One could imagine this movement being performed as an anthem in church services or at funerals, and moving its audiences to tears.

The final section sets the remaining eight verses of the Stabat mater sequence, uniting all the forces employed into two substantial and extended movements totalling nearly a quarter of an hour. In the first of these movements a new consolatory saxophone melody emerges, and it is this that will eventually come to dominate the closing pages of the work after a brief but effective evocation of the Last Judgement. It is in this echo of the Dies irae, however, that the music does, I feel, fall short of its subject. Since the orchestra, apart from the saxophone soloist, is restricted to strings, the tremolando writing cannot help sounding rather dated – a sort of combination of the Mozart and Cherubini Requiems – and does not really conjure up the sense of sheer terror that we have come to expect in the aftermath of Berlioz and Verdi. Maybe Fauré and Duruflé were wise when they minimised their settings of these words. The engineers have done their best to add impact, with the forces of the string orchestra well in the picture, but this in turn has its own drawbacks, especially in the opening movements where the singers can sound comparatively distant. The texts and full translations are provided in the booklet, but there were occasions when words were repeated and where I had some difficulty in deciding precisely what the chorus were actually singing. On the other hand, in movements such as the unaccompanied A chorus of angels sang (track 7) the balances were absolutely right. Perhaps the work as a whole would benefit from different acoustics or microphone placements in different movements. Here, the resonant reverberation of The Lighthouse in Poole, where the work was first premièred to a standing ovation in June 2019, may not have been an ideal recording location, any more than was Coventry Cathedral for the première of Britten’s War Requiem.

The solo singing of Jennifer Johnston and Stephen Gadd, who also sang at the first performance, is superbly clear, and the playing of Amy Dickson on the soprano saxophone is absolutely superlative quite eschewing any inappropriate hints of jazz style. She is provided with a very substantial encore in the form of Canticle of winter, effectively a miniature tone poem for saxophone and string orchestra first performed four months after the choral work and inspired by Robert Frost’s famous lines “The woods are lovely, dark and deep, but I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep…”. The music begins with gently pastoral meanderings, reminding me of such beautiful antecedents as Moeran’s Silent waters or one of Delius’s North Country Sketches. In due course this material gives way to more elaborate textures, but in a rondo theme with variations it returns to the opening in a delicate conclusion. I would have loved the piece to be longer. As it is, the playing on the time of the CD is not generous, but the quality of the music compensates for that. The composer’s biography in the booklet informs us that Pietà is scheduled for “multiple performances” in 2019/20. Quite rightly, too. ---Paul Corfield Godfrey, musicweb-international.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex mediafire ulozto solidfiles global-files