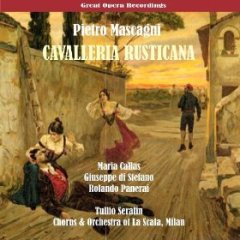

Pietro Mascagni - Cavalleria Rusticana (Callas) [1953]

Pietro Mascagni - Cavalleria Rusticana (Callas) [1953]

1. Cavalleria Rusticana: Preludio 1 2:37 2. Cavalleria Rusticana: "O Lola ch'hai di latti la cammisa" 2:36 3. Cavalleria Rusticana: Preludio 2 3:30 4. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Gli aranci olezzano" 8:35 5. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Dite, Mamma Lucia" 5:06 6. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Il cavallo scalpita" 2:40 7. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Beato voi, compar Alfio" 0:58 8. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Regina Coeli, laetare; Alleluja!" 2:34 9. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Inneggiamo, il Signor non è morto" 4:26 10. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Voi lo sapete, o mamma" 6:13 11. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Tu qui, Santuzza?" 3:48 12. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Fior di giaggiolo" 3:12 13. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Ah! Lo vedi, che hai tu detto?" 0:39 14. Cavalleria Rusticana: "No, no, Turiddu, rimani, rimani" 5:29 15. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Oh! Il Signore vi manda, compar Alfio" 5:31 16. Cavalleria Rusticana: Intermezzo 4:04 17. Cavalleria Rusticana: "A casa, a casa, amici" 2:58 18. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Viva il vino spumeggiante" 2:47 19. Cavalleria Rusticana: "A voi tutti, salute!" 5:10 20. Cavalleria Rusticana: "Mamma, quel vino è generoso" 5:46 Santuzza - Maria Callas Turiddu - Giuseppe di Stefano Alfio - Rolando Panerai Lola - Anna Maria Canali Mamma Lucia - Ebe Ticozzi Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano Tullio Serafin – conductor

Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana was the third complete opera recording for EMI [Columbia/Angel] that Callas took part in, and the second under the aegis of La Scala, Milan. Sessions took place at the beginning of August 1953 at the Basilica of Santa Euphemia, the theatre being shut in the summer. The recording was first published in April 1954. Like others she had already made, La Gioconda [Cetra], Lucia di Lammermoor [EMI] and Elvira in I Puritani [EMI], Santuzza she sang in the theatre, although she had not done so since her Athens days before World War II, when she made her first appearance on stage in the rôle at the age of fourteen in 1938. In the 1954/5 La Scala Season it was announced that she would do so again, under Leonard Bernstein, but in fact she did not, nor would she ever undertake it again.

Although Boito’s Mefistofele [1868] and Ponchielli’s La Gioconda [1876] (with libretto by Boito), contain some ingredients of verismo, Cavalleria rusticana, a one act work first given at the Costanzi, Rome in 1890, was archetypal of the new style. A swift moving passionate tale of betrayal and revenge it remained for the next century, with its twin, Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci [1892], one of the most popular operas. Santuzza was created by Gemma Bellincioni [1864-1950], whose repertory in her youth included Lucia and Elvira in I Puritani and later Giordano’s Fedora and even Strauss’s Salome, the variety of which suggests she had something in common with Callas. Although photographs of her in the Dance of the Seven Veils testify to her terpsichorean skill, her voice, records leave little doubt, was nothing remarkable. She was a noted dramatic soprano, but the term did not then refer, as it does today, to the size of a voice, rather to her histrionic prowess.

In the course of time, as the verismo style became more popular, reputable Santuzzas, with the increasingly intemperate playing of the orchestra, became increasingly concerned with the production of more powerful voices and more telling chest registers. Noted exponents included sopranos like Giannina Arangi-Lombardi [1891-1951], Giuseppina Cobelli [1898-1948], Iva Pacetti [1898-1981] and Lina Bruna Rasa [1907-1995], and mezzos like Ebe Stignani [1903- 1974], Giulietta Simionato [born 1910] and Fiorenza Cossotto [born 1935]. Although there is in Callas’s deployment of her registers something of their style; at the beginning, for example, as Santuzza laments to Mamma Lucia her being excommunicated, ‘sono scomunicata’, the first six of the seven syllables are all set on middle E; in these she uses chest voice, then gradually, as she lightens the tone, and the tessitura rises to top A, she is able to shift almost imperceptibly into middle voice, and does not have to indulge in crashing gears and those obtrusive register breaks so beloved of many Santuzzas.

She sings the aria Voi lo sapete, in which Santuzza tells her tearful tale of how Turiddu has deserted her for Lola, Alfio’s wife, in verismo style imbuing it with a characteristic vocal plangency; but she does not forget it is the singer’s business to indulge her listeners, and not herself. In so doing she renders the aria with such exactitude and precision that she makes it, one could say, almost classical. Towards the end of the first part there is an impeccably attacked fortissimo high A, and then the same perfection in her delivery of the piano F sharp at the beginning of the phrase ‘Priva dell’onor mio’. Her effects are never at the expense of the music. On the G, on the word ‘piango’ [I weep], she contrives a lachrymose effect not by gasping or by an uneasy selfindulgent lurch in the line, but by making an almost acciacatura from the register break an octave below. On all her records there is her musical accuracy to admire.

The only surviving films of Callas, as Tosca in Act II (at the Met, New York [1956], the Paris Opéra [1958] and Covent Garden, London [1964], show through the years, notwithstanding declining vocal resources, how her Tosca became increasingly more assured, an assumption – nevertheless were these the only souvenirs of her we possessed, how little of her art would have survived! There have been many great Toscas, too many to list here, but only one Callas. Like Caruso and Chaliapin, whose recordings testify to their greatness, her art had no precedent; she was not the consummation of tradition, but something new and different that suddenly appeared, breaking all the rules. Now she has been dead more than a quarter of a century and her stage career over more than forty years, yet there are more of her records available today than there have ever been.

Giuseppe Di Stefano, born in 1921 near Catania, Sicily, had a brilliant but short career. His was one of the most beautiful lyric tenor voices of the last century. He began singing light music then, following a brief period of study with the baritone Luigi Montesanto, made his opera début in 1946 as Des Grieux in Massenet’s Manon at Reggio Emilia, after which his rise to fame was rapid. In 1947 he appeared at La Scala, Milan, also as Des Grieux, and in 1948 at the Metropolitan, New York, as the Duke in Rigoletto. At first his repertory included Fenton in Falstaff, Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Rinuccio in Gianni Schicchi, Alfredo in La traviata and Faust, but it did not take long before he began undertaking heavier rôles, such as Cavaradossi, Don José in Carmen, Radames in Aida, Canio in Pagliacci and even Alvaro in La forza del destino. Sadly the great years of his career were soon over, and by 1961, trying to make more out of his voice than nature had put in, he made his last appearance at La Scala. From 1944 for HMV he recorded songs and arias, and from 1953 for Angel/Columbia, with Callas, Edgardo, Arturo, Cavaradossi, Turiddu in Cavalleria rusticana, Canio, the Duke, Manrico in Il trovatore, Rodolfo, Riccardo in Un ballo in maschera and Des Grieux in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut.

The baritone Rolando Panerai [b.1924], born at Campi Bisenzio near Florence, had a long and distinguished career. After completing his studies in Florence and Milan, with Armani and Tess, he made his debut at the Comunale, Florence in 1946 as Enrico in Lucia di Lammermoor. Thereafter his progress was rapid and extensive: in 1947 he appeared at the San Carlo, Naples; 1952 at La Scala, Milan; 1957 at the Salzburg Festival; 1958 at San Francisco and 1960 at Covent Garden, London. He sang elsewhere throughout Italy, and in Austria, Germany and France. His substantial repertory included Apollo in Gluck’s Alceste, the High Priest in Samson e Dalila, Mozart’s and Rossini’s Figaro, Masetto in Don Giovanni, Guglielmo in Così fan tutte, Paolo in Simon Boccanegra, Marcello in La Bohème, di Luna in Il Trovatore, Silvio, Germont in La Traviata and in 1962 at La Scala he created the title rôle in Turchi’s Il buon soldato Svejk. Later in his career, in traditional fashion, he graduated from Ford to Falstaff and undertook Don Pasquale and Dulcamara in L’elisir d’amore. In a 1950 RAI broadcast he is Amfortas in Parsifal with Callas’s Kundry and, nearly half a century later, Germont in a telecast of Traviata conducted by Mehta. His voice was an attractive sounding but lyric instrument. For EMI [Columbia/Angel] with Callas, as well as Alfio, he recorded Silvio, di Luna and Marcello.

Tullio Serafin (1878-1968), born at Rottanova di Cavarzere, near Venice, was one of the great conductors of Italian opera. After studying at the Milan Conservatory at first he was a violinist in the orchestra at La Scala, Milan, then in 1900 at Ferrara began a career as conductor. Engagements followed in Turin and Rome. Through more than half a century he appeared at Covent Garden, London (1907, 1931, 1959- 60), La Scala, Milan (1910-1914, 1917, 1918, 1940, 1946-7), Colón, Buenos Aires (1914, 1919, 1920, 1928, 1937, 1938, 1949, 1951), San Carlo, Naples (1922-3, 1940-1, 1949-58), Metropolitan, New York (1924-34), the Rome Opera (1934-43, 1962), Lyric Opera, Chicago (1955, 1957-58), and numerous other opera houses in Italy and abroad. His repertory was vast. He conducted conventional and unconventional operas as well as introducing a variety of new works and worked with numerous famous singers, including Battistini, Chaliapin, Ponselle, Gigli, Callas and Sutherland. His recording career was exhaustive and embraced the HMV (1939) Verdi Requiem as well as both EMI [Columbia/Angel] Normas [1954 and 1960] with Callas. ---Michael Scott, naxos.com

download: uploaded mega 4shared mixturecloud yandex zalivalka mediafie ziddu