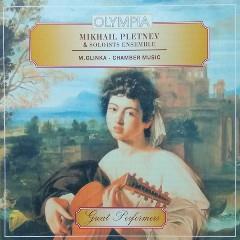

Mikhail Glinka - Glinka Chamber Music (2003)

Mikhail Glinka - Glinka Chamber Music (2003)

Septet In E Flat Major For Oboe, Bassoon, Horn, Two Violins, Cello And Double Bass (1823) (20:11) 1 I. Adagio Maestoso - Allegro Moderato 8:19 2 II. Adagio Non Tanto 4:58 3 III. Menuetto 3:31 4 IV. Rondo. Allegro 3:19 Serenade On Themes From Donizetti's Opera 'Anna Bolena' For Piano, Harp, Bassoon, Horn, Viola, Cello And Double Bass (1832) (20:05) 5 Largo (Introduction) - Cantabile Assai - Moderato - Larghetto - Presto - Andante Cantabile - Finale. Allegro Moderato Divertimento Brilliante On Themes From Bellini's Opera 'La Sonnambula' For Piano, String Quartet And Double Bass (1832) (13:17) 6 Larghetto - Allegretto - Vivace Grand Sextet In E Flat Major For Piano, String Orchestra And Double Bass (1832) (25:00) 7 I. Allegro 11:59 8 II. Andante - (Attacca) III. Finale. Allegro Con Spirito 12:59 Bassoon – Alexander Petrov (tracks: 1-5) Cello – Erik Pozdeev Double Bass – Nikolai Gorbunov (tracks: 7-9), Rustem Gabdulin (tracks: 1-6) Harp – Natalia Tsekhovskaya (tracks: 5) Horn – Igor Makarov (tracks: 1-5) Oboe – Alexander Koreshkov (tracks: 1-4) Piano – Leonid Ogrinchuk (tracks: 5,6), Mikhail Pletnev (tracks: 7,8,9) Viola – Andrei Kevorkov (tracks: 5,6-9) Violin – Alexei Bruni, Mikhail Moshkunov (tracks: 1,3,4,6-9)

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka: Grand Sextet in E flat major (1832). Born near Smolensk into the landowning class, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka was in St Petersburg from 1817 to 1830, save for a visit to the Caucasus. He became a skilled singer and pianist, taking three lessons from John Field and impressing Hummel, whose piano-writing clearly influenced the Grand Sextet. With little formal grounding he wrote several songs and imitated Classical forms in a number of chamber works. In 1830 he travelled to Italy where he met Mendelssohn and Berlioz, Bellini and Donizetti. The last two influenced him strongly and he wrote a number of pot-pourris on themes from their operas to please the numerous ladies with whom he fell in love. He himself describes the circumstances surrounding the composition of the Grand Sextet in his Memoirs of 1854 – he was living near Lake Maggiore (for his continually troublesome health) when he became infatuated with his doctor’s married daughter, a highly cultured and beautiful woman who had entertained Chopin the year before:

I naturally visited de Filippi’s daughter frequently – the similarity of our upbringing and our passion for the same art could not but bring us together. Because of her interest in the piano I began for her a Sestetto Originale, but later on, having finished it in the autumn, I was compelled to dedicate it, not to her, but to a female friend of hers.

You see, I had to cease my frequent visits because they were exciting suspicion and gossip. De Filippi was not a little concerned at this, and in order to put a stop to the unhappy business a bit more smoothly, he purposely took me to see his daughter the last time; we rowed about Lake Maggiore for almost the entire day in rather unpleasant weather, which indeed more or less matched our low spirits.

This was to be one of his last ‘Italian’ works: ‘Longing for home led me, step by step, to think of composing like a Russian.’ The next year he headed north, to Vienna and Berlin, where he pursued his only systematic course of study, before returning to Russia in 1834. Two years later, A Life for the Tsar was performed to a rapturous reception, followed by Ruslan and Lyudmila; together they established a completely new Russian school.

The first movement of the Grand Sextet, Allegro, opens with a bold motto-theme in the piano, setting the tone for its dominant solo role throughout the work. A conventional structure in sonata form follows, with an elegant first subject and a suave second theme which first appears on the cello. The development is simple, but the recapitulation is unusual in that it brings the second theme back in the submediant (C major), a device which recurs in the finale.

The Andante is a delightful serenade in G major with a gypsy interlude on the violin for the middle section. It leads directly into the finale, Allegro con spirito, a vivacious movement, again in sonata form, with three main themes: the first is full of cross-accents and unexpected barring; the second has an unashamedly operatic accompaniment; and the third contains the only true ‘Russian’ touch in the work – an extended melody whose modal basis prevents it from settling in any one key. ---hyperion-records.co.uk

The manuscript to Mikhail Glinka's Septet composed in 1823 lay moldering away in the dusty archives of the Russian State Library until the centenary of the composer's death, when the well-known Russian composer Vissarion Shebalin produced a score from which a set of parts were created and published some years later. Like much of his early music, the Septet was written for a specific occasion of home music making on his parents country estate in the autumn of 1823. In later life, Glinka, like many other composers, attached little importance to the works of his youth, including this Septet, which no doubt explains why he did not take the trouble to publish it. However, the fact remains that it is one of the few works for septet in which the oboe takes a part, rather than the clarinet. And it is perhaps the only Russian septet from the first part of the 19th century. The work opens with a solemn Andante maestoso introduction. It immediately conjures up the era of the Vienna classics. The music of Haydn and Mozart and their contemporaries was just becoming known in Russian chamber music circles at that time and perhaps Glinka was familiar with the septets of Friedrich Witt or Conradin Kreutzer or Beethoven’s Op.20 Septet in the same key. The main part of the first movement, Allegro moderato, could well have been written by one of those Viennese composers although it has some chromaticism that one does not find in their works. The second movement, Adagio non tanto, is a set of variations based on a Russian folk melody. Next comes an elegant Mozartean Menuetto with telling use of pizzicato in the strings as an accompaniment. The toe tapping finale, Rondo, allegro, is a lively affair full of appealing melodies. ---editionsilvertrust.com

Deeply under the spell of Donizetti’s operas, Glinka was a frequent guest at the home of the Branca family. Judge Branca had two musically gifted daughters, playing piano and harp, respectively. To show his appreciation, Glinka put together a Serenade on operatic themes from Anna Bolena. Making sure that both daughters musically participated, he cast the work in 7 movements, and scored it for piano, harp, viola, cello, bassoon, and horn. Once printed by Ricordi, it became a huge commercial success, and the publishing house asked Glinka for another composition like it. Eventually, Glinka also added a set of solo piano “Variations brillantes on a Theme from Anna Bolena” to Ricordi’s catalogue. ---interlude.hk

yandex mediafire ulozto cloudmailru gett