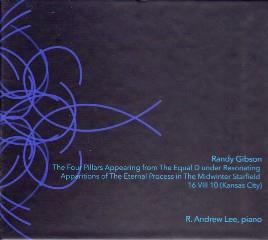

Randy Gibson - The Four Pillars Appearing ... [2017]

Randy Gibson - The Four Pillars Appearing From The Equal D Under Resonating Apparitions Of

The Eternal Process In The Midwinter Starfield 16 VIII 10 (Kansas City) [2017]

1 Opening 29:20 2 Establishing 24:30 3 Processing 16:02 4 Rising 51:37 5 Falling 15:06 6 Roaring 1:02:42 7 Resolving 11:39 R. Andrew Lee - amplified piano

Composer Randy Gibson is best known for his compelling experiments with intonation. R. Andrew Lee is the go-to pianist for Wandelweiser and minimalist-oriented music. On Gibson’s The Four Pillars Appearing from The Equal D under Resonating Apparitions of The Eternal Process in The Midwinter Starfield 16 VIII 10 (Kansas City), he meets Lee in the middle, creating a mammoth work out of very restricted means. The pitch material of the piece consists of just seven notes: D in all the octaves on a concert grand piano in equal temperament. Added to this are amplification and a small amount of electronic manipulation, designed to add resonance to the overtone vibrations taking place.

Irritable Hedgehog’s recording is a single unedited live performance from 2016 at University of Kansas City Missouri, with electronics realized alongside the piano part. Clocking in at some three-and-a-half hours, Lee deserves credit for a tour de force of stamina, focus and, perhaps above all, musicality in shaping the repeating pitches into countless varied phrases. Gibson is a master of deploying overtones. He has figured out how to exploit the various spaces between D’s to gradate the appearances of the harmonic series’ upper notes, or partials, and to maximize their potential. Shimmering conglomerations of overtones abound in The Four Pillars … it is certainly not a piece just about D! And while pitch serves as a focal point, it is worth mentioning that the piece’s overall shape, labyrinthine in scope, and its localized rhythmic gestures are equally well conceived. Four Pillars is one of the most compelling pieces yet from Gibson, and is Sequenza 21’s Best Drone Recording of 2017. ---Christian Carey, sequenza21.com

Minimalism is all the rage these days, or maybe, it’s best to call it minimalism light. The peril-fraught descriptor is used here with a mixture of reverence and trepidation. Watching over the past 30 years or so as it moved from outsider to insider status has been an enlightening and maddening experience. As with all musical genres that took the trip through the Maxian Idea and Idiology Camera Obscura, Minimalism’s garb has changed to the point where this softened and often saccharine version is being called Neoclassicism. How refreshing to dive headlong into something deep and long, a healthy dose of “authenticity” amidst the dross, and Randy Gibson’s recent long form and uncompromising masterpiece, performed with consummate skill and nuance by R. Andrew Lee, is just that.

I claim very little understanding of the Four Pillars, a tuning system Gibson has been developing since 2010. The impetus for such a study is Gibson’s immersion in the music and philosophies of his teacher, La Monte Young. If there is a predecessor to Gibson’s four-hour journey, it is most likely Youngs six-hour Well-Tuned Piano, a marvel of tuning and temporal flow which, like Gibson’s piece, is divided into seven sections with descriptive titles. In brief, Young’s magnum opus consists of long and unfolding improvisations based on a chord which comprises overtones related to a fundamental E-flat low enough to be inaudible, sitting well below even a Bosendorfer’s lowest pitch. Gibson’s explorations use D as the fundamental, and for him, it’s an entirely audible point of departure. For reasons that would render such micro-tonal tuning intricacies in diverse environments impractical, Gibson and Lee worked together to create an electronic realization through which the harmonic implications of that fundamental D emerge with no chords being played.

Franz Liszt’s sole piano sonata begins with a single G, but it is preceeded and followed by silence; Liszt notates the silence with a rest preceding the pitch. This recording of Gibson’s piece begins with a similarly proportional silence, an extraordinary invocation, or invitation to partake in the D’s that follow. Right out of the gate, Irritable Hedgehog’s commitment to making superb piano recordings is evident as Lee’s silky-strong touch on middle D shapes each attack. Each corresponding and glacially slow decay is captured with warmth and accuracy by feats of expert engineering. As the D moves through pitch space, the recording environment, its miniscule ambient sounds and the piano’s place in it come into focus, but just as it does, a subtle change begins to occur. The piano attacks begin to take on additional weight, a superhuman clarity. They subdivide, the plumby click of hammer hitting string becoming an immediate and enhanced reflection of itself, taking on definite but somehow elusive shades of color and pitch. The tones themselves bloom, or rather, they become seeds, sprouting leaves and branches of tintinnabulating harmonics; to call them overtones would be accurate but would fail to describe their subtle and increasingly pervasive impact. Some take on sibilant qualities, some ghost pitches of a harmonic structure (to use the conventional term chord would border on impertinence) whose implications are paramount to this music as it takes flight. Despite near staticity, half an hour flies by.

What is the writer to do when confronted by an experience of such power and immensity? Just a glance at the section titles, like “Rising,” “Falling” and “Resolving” give the impression of motion caught in tableau, and though they are accurate to the music they seek to encapsulate, they say nothing of the monumental forces at work as the music travels its recursive path. Any linear development is in micro-details; the plumby hammer clicks subdivide further and create their own percussive melodies, the piano enters into dialogue with itself via electronic processing, and registral interplay becomes more inclusive. Unity comes from the realization, often difficult to fathom, that all stems from those recurrent D’s, that the D gives rise to any sense of harmony throughout the work’s development, and harmony is actually quite palpable at certain moments. If there is a progression to the music itself, it might be heard as a series of slow arcs determined by dynamics, but even this attempt at some sort of visual or metaphorical representation fails utterly to capture the multilayered recurrences in which performer, composer and their attendant processes engage. At its loudest moments, in “Roaring,” the closest point of comparison might be to a waterfall at close range, so vast and visceral is the sound world evoked by low-register repetitions and their amplified harmonics. The piano does not become orchestral, because, again, such a conventional word does not do justice to the layers of metallic sheen over a single tone or to the way that tone and its trails of implication travel through a space filled with varying harmonic densities whose existence is so poignantly fragile.

After it’s all over, after the rising, falling and roaring regroup around the keyboard’s center, those single pitches can’t quite be heard as they were at the outset. The piece’s implications are as large as the music is diverse, its purpose as unified as the one note that births it. I have never heard piano and electronics joined in such complete symbiosis and to such organically singular effect. Of course, an unsympathetic performer could bring even such an edifice as this crashing to the ground. R. Andrew Lee’s deep immersion in music of this ilk (he recorded Dennis Johnson’s huge and pioneering November for the same label) constitutes much of the reason for its success. All elements converge to create one of the most important contributions to recorded piano music of at least the past 20 years. ---Marc Medwin, dustedmagazine.tumblr.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):