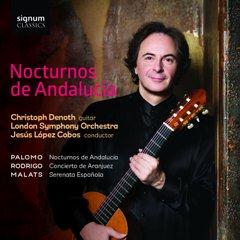

Palomo - Nocturnos de Andalucía Rodrigo - Concierto de Aranjuez (2016)

Palomo - Nocturnos de Andalucía Rodrigo - Concierto de Aranjuez (2016)

Lorenzo Palomo - Nocturnos de Andalucía[40'06] 1 Brindis a la noche 'A toast to the night'[8'02] 2 Sonrisa truncada de una estrella 'Shattered smile of a star'[4'22] 3 Danza de Marialuna 'Dance of Marialuna'[13'12] 4 Ráfaga 'Gust of wind'[2'03] 5 Nocturno de Córdoba 'Nocturne of Córdoba'[5'09] 6 El Tablao 'The flamenco stage'[7'18] Joaquín Rodrigo - Concierto de Aranjuez[23'09] 7 Allegro con spirito[6'18] 8 Adagio[11'28] 9 Allegro gentile[5'23] 10 Joaquín Malats - Serenata Española (Transcription from Impresiones de España)[4'22] arr. Christoph Denoth Christoph Denoth (guitar) London Symphony Orchestra Jesús López Cobos (conductor)

For all the great and deserved success of Joaquín Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez, there has not been a great outpouring of guitar concertos since. Part of the problem facing any composer who considers writing such a concerto is simply one of balance: rather like the harpsichord, the classical guitar has a modest volume of sound, and furthermore—when well played—a subtle range of tones which could be easily drowned by orchestral accompaniment. Which is precisely why Lorenzo Palomo’s Nocturnos de Andalucía (Andalusian Nocturnes), scored for a full symphony orchestra, rather than Rodrigo’s modest 39-piece ensemble, is such a remarkable achievement, and has been acclaimed wherever it has been performed since its 1996 premiere by guitarist Pepe Romero.

Lorenzo Palomo was born in 1938 in the southern Spanish province of Córdoba. His hometown, Pozoblanco, is rich with the heritage and influences of its historic Moorish occupation (which lasted from the 8th century until the 13th century), not least in the spicy harmonies and melismatic, improvisatory style of its music. All this may be heard in his Nocturnos de Andalucía (Andalusian Nocturnes), written at the behest of his friend Pepe Romero. Romero gave its first performance in Berlin on 27 January 1996, with Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos conducting the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra: on that occasion, the fifth movement, ‘Nocturno de Córdoba’, was so warmly applauded that it was encored.

Palomo’s concerto is a substantial 40-minute suite scored for a full-sized symphony orchestra: pairs of woodwind, four French horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and a rich array of percussion. Yet so skillful is Palomo’s orchestration that the soloist is never once overwhelmed by those forces, though they are heard on occasion in full tutti. As if to declare the symphonic scope of the work, the opening ‘Brindis a la noche’ (A toast to the night) launches with the orchestra in full voice. One can immediately hear in the boldly spicy harmonies both the untamed, fiery nature of Córdoba music and the fact this is a 20th-century work: following the example of Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, composers of that century no longer tamed such discordant harmonies as composers in the late-19th century would have, but embraced such discords as the genuine expression of indigenous folk music. With the solo guitarist’s entry, a more reflective mood is introduced. At the soloist’s initiative, the music again livens up, the orchestra responding like a receptive audience: elements of dance, reflective ‘cantilena’ and speech-like interjections all take their place in this dialogue between guitarist and orchestra. The next movement, ‘Sonrisa truncada de una estrella’ (Shattered smile of a star), starts in relative calm, though the soloist’s music becomes gradually disquieted until a ferocious orchestral outburst shatters any sense of tranquillity. The composer’s programme note describes the movement thus: “The firmament cries in a clear night. On the very same day, a brave young man saw his life shattered like the smile of a star. As if in a dreadful dream, five o’clock strikes: the time of the fiesta. The orchestra cracks like a whip in a fortissimo of horns and strings together.”

In altogether lighter mood, at least initially, is the third movement, ‘Danza de Marialuna’ (Dance of Marialuna). Here Palomo takes direct inspiration from Spanish poet Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881-1958), depicting the girl in the poem ‘La niña de blanco’ (previously set by Palomo in his song cycle Una primavera andaluza): the girl dresses herself in white in preparation for dancing before her beloved, hoping that he may join her in that dance. Her dance—as presented by Palomo—is clearly based on Flamenco, yet weaves in other sources familiar to the composer from his hometown, including Arabian melisma together with melodic inflections and harmonies from traditional Jewish music. Ultimately, as in the poem, hers is a tale of unrequited love.

The fourth movement, ‘Ráfaga’ (Gust of wind), is a short scherzo in which the restless music of guitarist and orchestra suggests the rising and ebbing wind heard during an Andalusian night. The fifth movement, ‘Nocturno de Córdoba’ (Nocturne of Córdoba), offers balm after all the anguish of the previous movements, the soloist picking out a melody as if in a gentle serenade, eventually taken up by high strings, then by the rest of the orchestra. As the composer’s programme note describes it, “In the fragrance of a Córdoba night we hear the guitar’s pearly tones like drops of dew on the leaves of orange trees and jasmine vines.”

The suite ends with the festive ‘El Tablao’ (The flamenco stage). As the composer recalls: “In his youth, Lorenzo Palomo used to go to the Zoco in his beloved Córdoba, where, in summer, there would be an improvised tablao Flamenco. It was there, in direct contact with the artists of Flamenco, that his great passion and feeling for this style of music was born, later providing a veritable fountain of inspiration from which spring the Andalusian Nocturnes.”

Lovers of Spanish guitar music need little introduction to Joaquín Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez, whose central slow movement has become a much-loved and imitated international hit. The concerto is named after the gardens at Palacio Real de Aranjuez, the spring resort palace and gardens originally built at the behest of Philip II in the late 16th century, then rebuilt in the mid-18th century by Ferdinand VI. The gardens were purposely designed to offer refuge from the dust and drought of the Spanish central plains.

Although Rodrigo composed Concierto de Aranjuez in 1939, well after Bartók had written his innovative works, it is an altogether more mellow work than Palomo’s suite—and not simply because it is scored for a smaller orchestra of just 39 players. The work’s character is surely a reflection not only of the gardens that inspired it, but also almost certainly the political situation in which Rodrigo composed his concerto: the Spanish Civil War had just ended, overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic and establishing Francisco Franco as Spain’s authoritarian leader. What was required by the new regime was music affirming order, and Rodrigo’s work, by celebrating the palace gardens of an 18th-century monarch, using elegant yet still recognisably Spanish rhythms and instrumental hues, harmonised with this requirement. Furthermore Rodrigo’s concerto is in the traditional 18th-century three-movement form familiar to Mozart, in which lively first and third movements sandwich a melodious slow movement. Here the concerto’s outer movements present something of the lively dance rhythms of Spanish music, spruced up as if for presentation in a royal court, while the central movement suggests a more subjective picture of the gardens, warm yet well-watered by the Tagus and Jarama rivers.

Joaquín Malats (1872-1912) was a Catalan pianist and composer, who studied piano at the conservatories of Barcelona and Paris. He became a friend of Isaac Albéniz, who much admired Malats’s performances of his own Iberia suite. Malats’s Serenata Española was originally the second movement of the four-movement orchestral suite Impresiones de España, dedicated to novelist Benito Perez Galdos, a leading member of the Spanish Realism movement. Serenata became so popular that Malats made a transcription for solo piano. Today, it is perhaps best known in various arrangements for guitar. Christoph Denoth, having recorded one such solo guitar arrangement in a previous album (Signum SIGCD404), now finishes this programme with his own arrangement of Serenata Española as a concertante work for guitar and orchestra. ---Daniel Jaffé, hyperion-records.co.uk

download (mp3 @320 kbs):