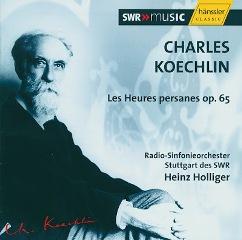

Charles Koechlin – The Persian Hours (2006)

Charles Koechlin – The Persian Hours (2006)

1. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 1. Sieste, avant le départ 2. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 2. La caravane (rêve pendant la seste) 3. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 3. L'escalade obscure 4. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 4. Matin frais, dans la haute vallée 5. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 5. En vue de la ville 6. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 6. À travers les rues 7. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 7. Chant du soir 8. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 8. Clair de lune sur les terrasses 9. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 9. Aubade 10. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 10. Roses au soleil de midi 11. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 11. À l'ombre, près de la fontaine de marbre 12. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 12. Arabesques 13. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 13. Les collines, au coucher du soleil 14. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 14. Le conteur 15. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 15. La paix du soir, au cimetière 16. Les heures persanes, Op. 65bis: 16. Derviches dans la nuit - Clair de lune sur la place deserte Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra Heinz Holliger – conductor Special thanks to THOMAS CIANNARELLA who's sent this album to us.

The Persian Hours is a suite of 16 short movements that exists both as a piano cycle and in this orchestral guise. It's a very special, atmospheric work, mostly very slow and dreamy, and except for three or four movements (À travers les rues; the mini-tone-poem Le Conteur; and the final Dervishes dans la nuit) is often extremely quiet. The orchestration is incredibly delicate and subtle, and it's entirely typical of Koechlin that although the piece is harmonically extremely audacious for its time (1913-19), the music is so subdued that you might not be aware of its frequent polytonal or atonal basis. In short, this is a very remarkable piece, but not one for casual listening.

It's also a terribly difficult work to record, and on the whole Heinz Holliger does a much better job than Leif Segerstam for Marco Polo. In the first place, Holliger has the better orchestra, but more importantly he knocks about 10 minutes off the timing of the entire cycle. Segerstam is entirely too static; Holliger manages to convey stillness without stasis, and that is the key that makes listening to the whole thing at a sitting possible (should you be so inclined). Pity the engineers, though. The dynamic range here is almost too wide, with soft bits incredibly quiet, making the few loud outbursts a bit too noisy. It's very good sound, as might be expected from the SWR team, but not quite ideal for the work. Still, if you're in the market for The Persian Hours, this is the way to go. -- David Hurwitz, ClassicsToday

"My dream has remained the same from the very beginning, a dream of imaginary far horizons - of the infinite, the mysteries of the night, and triumphant bursts of light."

So wrote the French composer Koechlin in 1947. Another Scriabin? Not quite. Koechlin seems to have had his dreams earthed and so avoided the perils of Messianic self-absorption. Nor did these dreams produce cerebral results. As late as 1933 and 1946 he produced major orchestral works such as Vers La Voûte Etoilée and Docteur Fabricius that pursue these arcana but steer clear of the voluptuary nature of Scriabin’s music.

The exoticism of the orient took a firm hold of European and others cultures throughout the period 1800-1950. Its forms were myriad from gimcrack salon to exalted inspiration. The Russians were particularly affected through Rimsky, Borodin and Ippolitov-Ivanov. The Americans succumbed as well with examples including Griffes Pleasure Dome and Farewell’s The Gods of the Mountains. In Belgium Biarent’s Contes’ d’Orient is a classic example - a very fine piece. In England Bantock wrote many oriental works including his philosophical masterpiece Omar Khayyam. Contemporary with the Koechlin work recorded here Delius wrote a magical score for Flecker’s play Hassan which in its final moonlit camel train departure comes close to Koechlin in Les Heures Persanes. In France there was an even long roster: Ravel (Sheherazade), Roussel (Padmavati, Evocations), Cras, Tomasi (some wonderful discoveries yet to be made there) and plenty of others.

Koechlin was not immune from this interest. His principal inspiration for Les Heures Persanes was the exotic travelogue by Pierre Loti, Vers Ispahan published in 1904. What we have here in sixteen movements is a study in atmosphere. The music is both subtle and refined. Sumptuous supercharged gestures are few and far between. Instead the music is often reflective and steadily paced. In each case the image is of a vista which has been internalised by the observer. The music concentrates on the thoughts rather than the scene.

If we ignore the two piano versions (Herbert Henck on Wergo and Kathryn Stott on Chandos) there are now two recordings of the Les Heures persanes. Around since 1993 is Segerstam’s Marco Polo (8.223504) recording with the Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz. Segerstam takes 68:56 to Holliger’s 58:03. I have compared the two. Holliger and Hänssler are businesslike yet despite the ten minute difference their reading rarely seems hasty. Segerstam favours a more languid approach and to my ears this works well with this dreamy vision of a work. In addition the Marco Polo team secured a very transparent and clear audio image in the Pfalzbau Hall in Ludwigshafen. The Sieste has a greater plangency with Marco Polo. In Caravane Holliger’s orchestral tone is hooded, less spot-lit while the Segerstam ostinato is bass deep and bitingly immediate. Travers la rue recalls Debussy’s La Mer and with Holliger is an urgent wild rumpus. On the other hand in the fleeting celebrations of Matin the Hänssler version is quicker and less mysterious. Marco Polo catches to perfection the shifting high harmonics and metallic majesty of the brass eruption. Honours are evenly divided in the shifting harmonics of Clair de lune but in Aubade Holliger is heart-easing in his evocation of bird-song while the Marco Polo is more earth-bound. Segerstam handles Le Conteur (tr. 14 - virtually a mini tone poem) with real tenderness but Holliger compensates with a much stronger presence for the gong and generally a better sense of fantasy. Swings and roundabouts.

I hope that Holliger will not stop and will go on to tackle Koechlin’s five movement Symphony of Hymns (1938: hymns to the sun, night, day, youth, life), La Cité nouvelle (1938, a fantasy tone poem after H.G. Wells - perhaps inspired by Things to Come - Koechlin was a keen cinema-goer), the First and Second Symphonies (1916, 1943-44), En Mer, La Nuit (a tone poem after Heine’s ‘North Sea’) and La Forêt (1896-1907) a further tone poem in two parts.

Across the Marco Polo-Hänssler divide my preference is for Segerstam, his plangent languor and superior recording transparency. If the work is at all important to you having both versions will provide rewards and revelations. ---Rob Barnett, musicweb-international.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega mediafire zalivalka cloudmailru uplea ge.tt