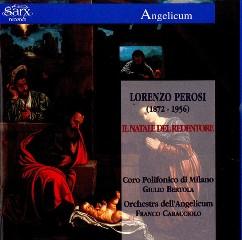

Lorenzo Perosi – Il Natale Del Redentore (1978/1997)

Lorenzo Perosi – Il Natale Del Redentore (1978/1997)

1 Parte Prima: L'Annunciazione 24:20 2 Parte Seconda: Il Natale 38:05 Maria - Mirella Freni (soprano) Storico - Claudio Strudthoff (baritone) Angeli - Giuseppe Nait (tenor), Jeda Valtriani (soprano), Ortensia Beggiato (mezzo) Coro Polifonico di Milano Orchestra Dell'Angelicum Di Milano Carlo Felice Cillario - conductor

Lorenzo Perosi (1872–1956) is hardly a household name. Even Grove Online can barely tease two paragraphs out of his biography. Yet, his oratorios seem to have enjoyed tremendous success at the turn of the century, attracting the attention of Romain Rolland and other notables. In addition to those 11 works, compressed into the years directly at the turn of the century (1897–1904), Perosi also wrote 33 masses, five concertos, 18 string quartets, and some other scattered items. But the church compositions have indeed continued to enjoy relatively frequent performances within their niche, including the active repertoire of the Sistine Chapel choir. Many of these works, including masses and several of the other oratorios, are obtainable on the Bongiovanni label. This, however, is my first encounter.

Perosi’s fifth oratorio, The Birth of the Redeemer , dates from 1899, the second year of his tenure as director of the Sistine Chapel choir, and plies a surprisingly avant-garde course, at least compared to what I knew of contemporary Italian music (restricted as it is to Puccini and the verismo opera composers). While the vocal parts tap into a highly wrought operatic vein, the shifting colors, pure instrumental groupings, and even the handling of the chorus may recall for some listeners the world of the early Mahler symphonies (especially the Second). Effects are spatial and antiphonal rather than explicitly dramatic or narrative. Elsewhere, the music eclectically draws from Palestrina-like Renaissance counterpoint formula (in a capella passages), or the world of 19th-century sacred music from Schubert to Parsifal . One is struck by occasionally adventurous, vagrant chromatic harmonies, as well as many sustained ninth and added-sixth chords. Extended, winding passages for horn choir lead into impressively ponderous episodes for brass alone. In addition to the Palestrina imitations, Perosi deploys other learned devices with a sure hand, including a throbbing, agitated fugue for strings near the beginning of part II that recalled for me the Berlioz of L’enfance du Christ , a work Perosi’s oratorio often resembles in atmosphere (even if it falls short in drama or subtlety).

The text is standard Nativity boilerplate, cobbled from scripture and standard Latin hymns (“Ave Maria,” “Ecce ancilla Domini”), but Perosi responds to it inventively. The extended instrumental interlude, “La notte tenebrosa,” employs oboes and flutes to suggest an appropriately pastoral mood, though the lush and often-chromatic string entrances suggest echoes of Wagner or, more directly, of Perosi’s older contemporary Pfitzner. Among the soloists, the most effective voice belongs to the most omnipresent, the baritone Historian (Storico), whose warm, covered timbre carries smoothly throughout his many speeches. However, even he evinces some strain in his upper register near the end of “La notte tenebrosa.” The other soloists blend well in ensembles, but fare far less well in their exposed moments. The Maria, soprano Emilia Bertoncello, waxes squally and shrill with her climactic “Ecce ancilla Domini” near the end of part I, though elsewhere her tone is more consistent and pleasant. The tenor finds himself overmatched by his high-lying “Spirito sancto” phrase at the opening of the same movement, his occasional choked entrances, shaky pitch, and bellowed high notes rendering some parts of the recording almost unlistenable.

For the most part, though, the provincial, North Italian ensemble forces play and sing the stuffing out of the piece, with only a few lapses in wind intonation and attack. In keeping with the usual practice of the Bongiovanni label, the recording is taken from a live broadcast (from October 2007). Latin texts are provided, along with translations in Italian and English. Although die-hard Elgar fans are likely to remain unimpressed by the work, it is still recommended for listeners curious about the byways of church music at the fin de siècle , particularly south of the Alps. And, countless little touches do stay in the mind, such as the woodwind bird calls accompanying the soaring angelic chorus “Gloria in altissimo Deo” in the middle of part II.

The second disc is filled out by a curious antiphonal piece for orchestra, recorded in 2000 in a notably more echoing space and with a less accomplished orchestra. Titled The Village Festival , this 1912 work has a roughly ABA structure and is driven by pulsing ostinatos. Much of the noisier material consists of banal rising and falling scale passages, not always executed accurately or in tune. I can’t imagine I will be returning often to this trifle, even when I listen to the oratorio. ---FANFARE: Christopher Williams, arkivmusic.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):