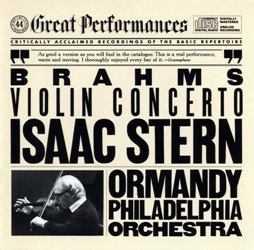

Brahms - Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra Op.77 (1973)

Brahms - Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra (1973)

I. Allegro non troppo II. Adagio III. Allegro grocioso ma non troppo vivace Isaac Stern – violin Philadelphia Orchestra Eugene Ormandy – conductor (CBS Masterworks – Great Performances 44)

If anyone - and I doubt they can still get away with it - wishes to claim that Eugene Ormandy had a "one size fits all" method of conducting, I entreat them to find a more Brahmsian, more Germanic, rendering of the third B's violin concerto than this recording. Eugene Ormandy's treatment of its opening phrases is at once so disciplined yet pliant - with the setup of the same sense of majestic forbearance and layered tonality he brings to his recordings of Brahms' symphonies. The tenuous overlapping of the strings with the winds alone is a textbook example of instrumental balance. Listeners can clearly understand why Ormandy was so renowned as a peerless colloborator. And this overwhelming tidal wave of sound comes even before Stern's violin has uttered a note!

Too often, I have heard other maestros conduct a concerto indifferently, on the mistaken assumption that it is, after all, the soloist's opportunity to shine -- not the orchestra's -- least of all, the conductor's. Such a passive approach runs counter to the composer's intentions; especially one such as Brahms, whose musical statements are of symphonic proportions, even in his concertos and sonatas (his First Piano Concerto was originally drafted as a symphony). Ormandy presents Stern with the proverbial "tough act to follow."

Isaac Stern's genius lies in the fact that with the singular voice of his violin he rises to the challenge -- and surpasses it. His violin cuts through the orchestra sharp as a stiletto, and never lets up in heightening the sense of drama.

Ormandy's genius lies in the fact that the orchestra's accompaniment never overwhelms Stern's violin, yet also never fades into the background, either; Ormandy's is a sympathetic and holistic approach, fluid in tempo and accommodating in dynamics in providing the perfect counter-balance to Stern's performance.

Stern and Ormandy performed and recorded many great concerti together while both were with Columbia: Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Mendelssohn, both of Prokofieff's. Stern always had the highest praise for Ormandy's uncanny ability to anticipate a solist's nuances. "Gene becomes an extension of your own phrasing and music making," Stern said in 1979. "It's almost as if he were taking part in your bowing as you play, because subtleties in pressure and phrasing -- if you're playing well you do them spontaneously -- he responds to instantly, even a millisecond ahead of time.

"I've often said," he joked, "that if you were going to catch cold and sneeze next week, Ormandy would already be there with a handkerchief -- you didn't know it was going to happen, but he did." Nowhere is this seamless melding of musical minds so apparent between the two than on this landmark performance.

Of all the recordings I've heard of this concerto, none can match Stern's and Ormandy's sense of tension-and-release, which is sustained from the introduction through the finale . It is, by far, the most intellectual performance I've heard -- yet so sanguine, so melodic. There is nothing sloppy or extraneous in Stern's playing: It is pure logic, an exacting rendition in which Stern is in command of every note. Like Heifetz' recording with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony (1958), this recording is very up-tempo. Yet, unlike Heifetz -- who sometimes dashes through a passage so quickly that he glosses over notes -- every note is endowed with purpose and intent.

The finale is breathtakingly bold, without ever being brash. It's one of the best examples of sustained and controlled passion I've heard on records -- akin to God holding a force of nature in his bare hands, unleashing it at the peak of its potency.

Both Stern and Ormandy thus have produced a musical document that speaks profoundly towards the respect and awe both men had before Brahms' oeuvre: I cannot tell the difference between Stern's approach towards the work and Ormandy's. Both musicians seem to be channeling the weighty and commanding German composer, but without getting bogged down in stale, scholarly, interpretation. Their passion for Brahms comes through with a clarity one usually associates with the iconoclastic composers, such as Mahler or Satie.

Recorded in 1959, this recording is one of the earliest stereophonic recordings in either Stern's or Ormandy's career. On the compact disc, though, you can't tell: The microphones catch every nuance every raspy bass and 'cello string, the ring of the brass, the rush of the wind as its passes through the flutes and the full range of Isaac Stern's virtuosic expression on his very dolce Guarnerius del Gesu.

This is a recording for the ages: It entertains, thrills and inspires. --- Interplanetary Funksmanship "Swift lippin', e... (Vanilla Suburbs, USA)

download: uploaded anonfiles yandex 4shared solidfiles mediafire mega filecloudio

Zmieniony (Poniedziałek, 02 Grudzień 2013 13:48)