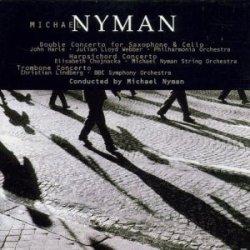

Michael Nyman - Three concertos (1997)

Michael Nyman - Three concertos (1997)

1. Concerto for saxophone, cello & orchestra: No. 1 2. Concerto for saxophone, cello & orchestra: No. 2 3. Concerto for saxophone, cello & orchestra: No. 3 play 4. Concerto for saxophone, cello & orchestra: No. 4 5. Concerto for saxophone, cello & orchestra: No. 5 6. Concerto for harpsichord & strings: No. 1 7. Concerto for harpsichord & strings: No. 2 8. Concerto for harpsichord & strings: No. 3 9. Concerto for harpsichord & strings: No. 4 10. Concerto for harpsichord & strings: No. 5 11. Concerto for harpsichord & strings: No. 6 12. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 1 13. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 2 14. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 3 play 15. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 4 16. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 5 17. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 6 18. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 7 19. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 8 20. Concerto for trombone & orchestra: No. 9 Double Concerto for Saxophone, Cello and Orchestra John Harle: soprano and alto saxophones Julian Lloyd Webber: Cello Philharmonia Orchestra Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings Elisabeth Chojnacka: harpsichord Michael Nyman String Orchestra Concerto for Trombone and Orchestra Christian Lindberg: trombone BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Nyman

Double Concerto for Saxophone, Cello and Orchestra. Commissioned by Mazda Cars (UK) Limited for John Harle, Julian Lloyd Webber and the Philharmonia, this Concerto was written in late 1996 and early 1997 and first performed at the Ropyal Festival Hall, London under James Judd on 8 March 1997. Though the individuality of each of the solo instruments is respected, there is a sanse in which a new combined single solo instrument is being created (at least for the first two thirds of the piece). Saxophone and cello constantly double each other in different octaves, play in each other’s characteristic registers, exchange material, shadow and decorate each other. Harmonically, the Concerto toys with the duality of the open (almost folk-like) and the sensual, the cleanly diatonic and the more muddily chromatic. It is only at that point in the work where a bitonal ‘sandwich’ is taken apart that the two soloistst briefly take on marginally separate identities.

The five connected sections of the Concerto are clearly defined but are sometmes broken up into subsections; some themes wander from section to section while others are ‘re-presented’ as (from quite early on) they recapitulate themselves and recombine with each other. The first three sections are each introduced by the soloists playing in unison or octaves. Sometimes the border between one section and another is marked by a lyrical, four-square waltz (presented in standard Q&A fashion).

Section 1: in two parts, both over a pedal D. The cello drags itself out of, and decorates, the sustained soprano sax line. The roles are the reversed before the violin section presents jagged rhythmic figures in a faster tempo. Section 2: led by the soloists with a decorated/diminutive version of what is subsequently discovered to be a slow C-minor (fake) waltz. Like Section 1, the second part is faster as the saxophone recomposes the jagged violin figure. Section 3: C-major, rustic irregular quaver theme first with soloists, later orchestrally. Section 4: slow, sustained music underpinned by a more ‘evolved’ harmonic lagnuage. Stretched chords, first decorated by alto sax, then cello (the reverse of Section 1). In a faster tempo the jagged violin figure from Section 1 is heard over a series of triads underpinned bitonally by an unrelated G-A-C chord. With a reminuscence on alto sax of the waltz diminution of Section 2 the soloists split apart—the alto plays in its lowest register with the upper part of the harmonic sandwich, while the cello plays in its lowest register a sustained melody with the lower part of the sandwich. A B-minor-ish sequence presents the only genuine solo, for cello, in the whole Concerto. Section 5, amongst other things, returns to the tempo and some of the material of the opening three sections and ends with a combination platter now featuring (for both doubling soloists) a more elaborate version of the high sustained cello tune of Section 4.

Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings. This Concerto was composed during the winter of 1994/95 for Elisabeth Chojnack, who gave the first performance with the Michael Nyman String Orchestra on 29 April 1995 in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, London. Its history is eccentric and cumulative. I had met Elisabeth in Paris about a year earlier while I was working on the soundtrack for Diane Kury’s film A la folie (Six Days, Six Nights). I was attempting to persuade her to play my solo piece The Convertibility of Lute Strings (1992) but she expressed a passion only for tangos. As luck would have it, one of the cues for the Kurys score was what I fondly called a tango. Elisabeth showed interest in this and I subsequently turned it into a harpsichord solo. Sadly, during the writing of the piece my friend the composer Tim Souster died tragically. Elisabeth’s enthusiasm for Tango for Tim encouraged me to write the Concerto for her.

The Concerto is shaped as a very simple ABA form—the outer sections, derived from The Convertibility of Lute Strings, enfold an elaborated version of Tango for Tim. After the first performance, Elisabeth decreed that thez true potential of the Concerto could only be fulfilled by the addition of a cadenza. This was duly composed in the summer of 1995—a toccata derived from harmonies first heard in the immediate post-Tango for Tim, Convertibility material. (Elisabeth subsequently ordained that the cadenza could also have a life outside the Concerto as a concert piece if it had a few extensions added. Hence—inevitably, the title of the piece—Elisabeth Gets Her Way.)

Concerto for Trombone and Orchestra Though the Trombone Concerto, which .I wrote for Christian Lindberg and the BBC Symphone Orchestra between February and September 1995, is the fourth in my Concerto Series—it follows Where the Bee Dances (for soprano saxophone, 1191), The Piano Concerto (1993) and Concerto for Harpsichord and Strings (1995)—it is the first where the releationship between soloist and orchestra is conceived as a dramatic narrative, even though it telles no specific story.

The background to the Concerto—apart from Christian Lindberg’s virtuosity and remarkable showmanship—is a text by the Marxist historian E.P. Thompson on ‘Rough Music’ which has been haunting me for years and which the Trombone Concerto has helped to exorcise. Thompson defined Rough Music as “the term which has been generally used in England since the end of the 17th century to denote a rude cacophony, with or without more elaborate ritual, which usually directed mockery against induviduals who offended against certain community norms”. This cacophony was usually produced by a “band of motley musicians, beating a fearsome tattoo on old buvkets, frying pans, kettles and tin cans”.

The Concerto draws on the imagery of such practices by confronting metal and wood with metal and wood: the trombone/offender has is constant support system of the brass and string sections which are persistently and vigorously opposed by metal percussions and woodwind, who always hunt in packs (apart from the rare occasions when the bassoons attempt to invade the trombonist’s space). Initially the metal percussion instruments are tuned and benign, but during the course of the piece become increasingly hostile. The percussion instruments constantly crowd out the soloist by means of noise, whereas the woodwind deny the trombonist space and contradict him harminically.

The Trombone Concerto proceeds though a series of short musical cul-de-sacs down which the soloist may get trapped or from which he may escape (and which lay down thematic, rhythmic or harmonic ‘trails’ that are followed erratically throughout the work) until the trombonist asserst his authority with a longer jig-like sequence (more in keeping with the ‘country’ rather than ‘city’ context of Rough Music).

This Concerto was commissioned by the BBC for the 300th anniversary of the death of Purcell. In homage to the composer whose music first found its way into my scores with the Draughtman’s Contract in 1983, it seemed appropriate in a concerto for trombone to quote from Purcell’s brass music. Accordingly, the five cadences from the Funeral Music for Queen Mary appear three times: first, backed by gongs and tamtams on pulsing woodwind ‘attacking’ a trombone solo; second, on trumpets and trombones whcih the pulsing woodwind attempt to (chromatically) annihilate, and finally as the backing to potent string scales over which the soloist is melodically triumphant. This mood of triumphalism is immediately broken by the three percussionists beating out a football-derived chant (QPR v Newcastle, 1994-95 season—“COME-ON-YOU-Rs”) on metal filing cabinets. This pulse (usually at odds rhythmically from the rest of the orchestra) drives the final minutes of the Concerto till the trombonist finds himself in the same sentimental corner he was in at the beginning—a brief moment of respite beofre another session of pursuit perhaps… but the woordwind are still stalking, and the steel drums have infiltrated his tune….--- michaelnyman.com

This CD contains three concerti written by Nyman in the late 1990s: his Double Concerto for Saxophone and Cello, his Concerto for Harpsichord and Orchestra, and his Concerto for Trombone and Orchestra. Of these, the outer two works are fine pieces, full of excitement, lyricism and interest; well worth repeated listening. The Harpsichord Concerto, however, is not nearly as successful a composition. The liner notes imply a certain friction between composer and the soloist he was writing for, Elizabeth Chojnacka. Phrases like "Elizabeth decreed that the true potential of the Concerto could only be fulfilled by the addition of a cadenza," "I was attempting to pursuade her to play my solo piece" and "Elizabeth subsequently ordained that the cadenza could also have a life oustide the Concerto as a concert piece." indicate to me a certain difficulty in the process of composition, perhaps even to the extent that the composer was not entirely convinced of the quality of the final product. I'm certainly not--there are good moments, particularly the final section, but overall the piece is annoyingly repetitious--and yes, I'm fully aware of the influence of minimalism on Nyman's style. The harpsichord contributes little melodically, being limited to the most part to tinny repeated chordal patterns and ostinati. My teenage daughter was driven to distraction by this, and while our tastes diverge on the Backstreet Boys, I had to agree when she said it sounded like a musicbox gone mad. In fact, Nyman's done that sort of effect before successfully, but for me this attempt is a failure.

Why then do I give the CD 5 stars? The trombone concerto is a fabulous thrill ride that does Christian Lindberg, arguably the greatest living trombone soloist, proud. Nyman has cast the piece as an arguement between two antagonists, and the BBC Orchestra gives Lindberg a run for his money. Nyman's orchestrations are both imaginative and delightful. The percussion, missing entirely from the Harpsichord Concerto, has an especially rich palate--at one point the players play metal filing cabinets! Wind writing too is thrilling, and the whole is a fun romp that ducks into some very unexpected corners. Lindberg's done a great job for trombone literature, and this is one of his best contributions.

The Double Concerto for Saxophone and Cello that opens the disc is also a winner. It's much more lyric overall than the trombone concerto, but almost equally fascinating. Nyman has orchestrated the piece for the most part so that the two soloists act as a single role, a sort of new super-instrument. The instrumentation puzzled me when I first heard the title and I couldn't really imagine how such a piece would work; but clearly Nyman didn't have the same difficulty. Saxophonist John Harle and cellist Julian Webber do a fine job with this lovely piece, and the Philharmonia Orchestra back them superbly. ---Dr. Christopher Coleman

download: uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire solidfiles mega filecloudio nornar ziddu

Zmieniony (Wtorek, 04 Marzec 2014 13:41)