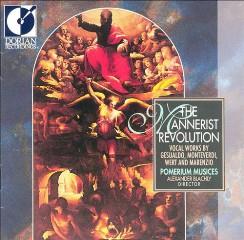

The Mannerist Revolution (1991)

The Mannerist Revolution (1991)

01 - Carlo GESUALDO. Tristis est anima mea [6:04] 02 - Claudio MONTEVERDI. Io mi son giovinetta [2:27] 03 - Claudio MONTEVERDI. Ohimè, se tanto amate [2:43] 04 - Carlo GESUALDO. Omnes amici mei [5:44] 05 - Giaches de WERT. Voi, nemico crudele [1:58] 06 - Giaches de WERT. Ahi, lass'ogn'or [2:15] 07 - Carlo GESUALDO. Tenebræ factæ sunt [6:47] 08 - Claudio MONTEVERDI. Cor mio mentre vi miro [2:08] 09 - Claudio MONTEVERDI. Piagn'e sospira [4:03] 10 - Claudio MONTEVERDI. Sì ch'io vorrei morire [2:44] 11 - Carlo GESUALDO. Velum templi scissum est [5:46] 12 - Carlo GESUALDO. Io tacerò [4:54] 13 - Carlo GESUALDO. Beltà, poi che t'assenti [3:21] 14 - Carlo GESUALDO. O vos omnes [4:04] 15 - Luca MARENZIO. Crudele acerba [2:48] 16 - Carlo GESUALDO. Solo e pensoso [5:23] Pomerium Musices: SOPRANOS - Rossana Bertini, Ruth Cunningham, Kathy Theil, Alessandra Visconti ALTOS - Karen Clark Young, Stephen Rosser TENORS - Peter Bannon, Gregory Carder, Michael Steinberger BASSES - Alexander Blachly, Tom Moore, Paul Shipper Alexander Blachly – director

The "mannerist" art of the late Renaissance stands worlds apart from the "Apollonian" art of the early Renaissance. Whereas the 15th century had sought power and beauty through integration, elegance and naturalism, the "avant-garde" in the later 16th century startled and provoked through the dynamic interaction of opposites. First in Italy, then elsewhere, the impulse we know as mannerism fueled a profound change in notions of what high art could and should strive to express. Maniera (literally, "style") was a term used in the 15th century in reference to "(good) manners"; but a century later, having evolved nearly diametrically, it was used in aesthetics with a meaning closer to "artificial," that is, what we now call "mannered." The hallmarks of mannerist art are disproportion, discontinuity, surprise, and, especially, novelty.

In literature, the revival of interest in Petrarch (d.1374) — many of whose works are charged with conflicting emotions — spurred several generations of 16th-century poets: Pietro Bembo, Lodovico Ariosto, Giovanni Battista Guarini, Torquato Tasso, Luigi Tansillo. Maria Rika Maniates has put in a nutshell Tansillo's more overt tendencies: "Violent descriptions and sharp conceits are piled one on top of the other in a paroxysm of anguish." In painting, mannerist artists such as Parmigianino, Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Salviati, and Giulio Romano set classical notions of high art on their head, portraying in exquisite detail elegant but skewed figures, often in conjunction with voluptuous nudity and other startling effects. In music, mannerism found expression in chromaticism, the unsettling quality of which, coupled with an increasingly direct musical rhetoric, enabled composers to "speak" through music the anguish, frustration, and sorrow of the poems they selected to set.

The primary musical arena for the developing mannerist style was the madrigal, a fundamental aspect of which is the use of four, five or more singers to express the thoughts and declarations of an individual, often in the first person. The history of the 16th-century madrigal is, in fact, a microcosm of the progress of mannerism itself. The musical language of the earliest madrigalists, who wrote in the 1520s and '30s, is heartfelt but gentle, responsive both to the inflection and the sense of the poetry, but more concerned with grazia (beauty) than with the effetto meraviglioso (marvellous or miraculous effect). Composers in the next generation, especially Cipriano de Rore (1516-1565) in the 1550s and '60s, wrote in a more intense style, incorporating into their music greater chromaticism, more outré devices, and increasing discontinuity. For Cipriano, Petrarch has become a favored poet.

Giaches de Wert (1535-1596) developed in his madrigals of the 1580s and '90s a new degree of musical pictorialism, capable of "representing" not just such natural phenomena as rivers, storms, and breezes, but also of capturing in music a spoken question — such as "Chi moi-rà, vita mia?" ("Who will die, mylife?"), in Voi, nemico crudele. Wert's younger contemporary, the native Italian Luca Marenzio (c.15531599), is so thoroughly at home in the madrigal idiom that for every poetic idea he finds an immediate musical equivalent. Marenzio is the master at creating wonderfully apt musical settings for the diverse images of "expressionistic" poems.

Carlo Gesualdo (c.1561-1613), focusing almost exclusively on texts of frustrated love, develops in his madrigals a language of uninhibited, outrageous, yet startlingly effective despair, carrying both chromaticism and musical rhetoric to a point previously unimagined. Indeed, Gesualdo's works, with their unending collisions of conflicting emotions, may be regarded as the pinnacle of musical mannerism — as the end of that particular road of artistic exploration. Interestingly, his works are marked by the very traits that Nikolaus Pevsner finds in the mannerist architecture of late-Renaissance Italy: " 'restlessness and discomfort,' the 'incongruous proximity of opposites,' the 'tendency to excess within rigid boundaries,' the 'intricate and conflicting pattern,' and above all 'no solution anywhere' " — to cite the summation by music historian Edward Lowinsky.

With Monteverdi (1567-1643), we are at the threshold of a new musical universe, one in which the a cappella madrigal will soon have no place. But Monteverdi's last essays in the form, his unaccompanied five-voice madrigals of Book IV (from which the five of his madrigals heard on this recording are drawn) and Book V, are the climax of the genre in their thematic continuity and virtuosic musical effects. These works are particularly brilliant in their integration of Netherlandish musical artifice — points of imitation, double and triple musical subjects, invertible counterpoint — with the emotional intensity of recited poetry.

We should not overlook the fact that the madrigalists' expression of despair and frustration is intimately connected with eroticism. Indeed, love, especially of the tormented and twisted varieties, is a subject from which the mannerist composers seem unable to escape. As the counterpart of the universally-understood erotic interpretation of the poets' "dying" and "resurrecting," the madrigalists after 1550 create an association of eroticism with chromaticism. Not surprisingly, it is in the works of the most morbidly erotic of all composers — Gesualdo — that chromaticism reaches its peak.

Regarding the ideal performance of mannerist music, we have a specific recommendation by a 16th-century critic who was also a theorist and composer. The following statement from Nicola Vicentino's L'Anticamusica ridotta alla moderna prattica (1555) should put to rest any claims for a "neutral" presentation of this repertory:

One must sing the words in accordance with the composer's intention, and express with the voice intonations accompanied by the words with their affects: now cheerful and now sad, now sweet and now cruel — and one must accompany the pronunciation of the words and the notes with expressive accents; and at times one uses a certain mode of proceeding in the performance of the compositions that cannot be written down, such as to sing piano and forte, fast and slow, and to change the tempo in accord with the text so as to express the effects of the passions and the music. . . . In secular music such a mode of performance will please the listeners more than an unchanging, even tempo, and the tempo must change according to the words, slower and faster . . and the experience of an orator is an example, for one can observe the orator's mode of speech, now with a loud, now with a soft voice, and slower and faster, and in this manner he moves the listeners more; this mode of changing the tempo stirs the soul.... ---Alexander Blachly, sonusantiqva.org

download (mp3 @320 kbs):