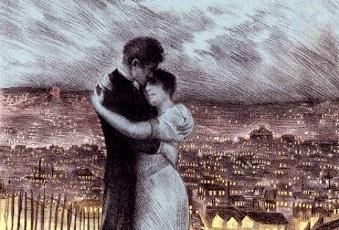

Gustave Charpentier - Louise (Paris 2007)

Gustave Charpentier - Louise (Paris 2007)

1. Act I 2. Act II A 3. Act II B 4. Act III 5. Act IV Louise: Mireille Delunsch Julien: Paul Groves Le père: José van Dam La mère: Jane Henschel Irma: Marie-Paule Dotti Camille: Natacha Constantin Gertrude: Anne Salvan L'apprentie/La plieuse/Une petite chiffonnière: Elisa Cenni Élise: Yun-Jung Choi Blanche: Adriana Simon Suzanne: Letitia Singleton Marguerite/La balayeuse: Cornelia Oncioiu Madeleine: Daniela Encheva Un noctambule/Pape des fous: Luca Lombardo Un chiffonnier: René Schirrer Un vieux bohème: Myoung-Chang Kwan Le chansonnier: Nicolas Marie Un bricoleur d'affiches/Gardien de la paix: Bartlomiej Misiuda Premier philosophe: Rodrigo Garcia Second philosophe: David Fernandez-Gainza Un peintre: Young Min Oh Un jeune poète: Shin Jae Kim L'étudiant: Hyun-Jong Roh Le sculpteur: Pascal Mesle Un apprenti: Caroline Bilbas La rempailleuse: Marie Cécile Chevassus La marchande d'artichauts: Joumana El Amiouni Le marchand de carottes: Fernando Velasquez Le marchand de chiffons: François Bidault Orchestre et chœurs de l'Opéra national de Paris Sylvain Cambreling - conductor Paris, Opéra Bastille - (15.IV.2007)

The plot of Louise will tax no one in its level of difficulty. Girl finds boy, girl runs away with boy over (unreasonable) parental objections, girl and boy are deliriously happy, parents fail to get girl to return home to stay, parents are miserable. Finis. No subplots.

Such simplicity in not necessarily a bad thing. Think of Madame Butterfly, which has almost as straightforward a story line. But Butterfly is one of the most popular operas, in constant play by opera houses all over the world. Louise, on the other hand, the only opera by Gustave Charpentier to survive in the repertory, is becoming a rarity onstage, largely perpetuated by French opera houses.

What Louise is really missing is not more plot, or even its absent narrative momentum, but deeper, more rounded character development. Each of the principals is a one dimensional embodiment of a small package of situation and feelings – Louise, the innocent, but adult, woman in love, restrained by possessive parents; Julien, the poor poet and ardent lover; the mean-spirited and rigid mother; and the loving father, selfishly unwilling to let his daughter go. None of them changes a whit during the course of the action and, when the final curtain comes down, you don’t know much more about them than you did at the beginning.

Butterfly sustains emotional involvement because through the accumulated detail of her simple story, an ever deeper understanding of her vulnerability and tragedy evolves. Then, too, Butterfly has a lot of gorgeous music to sing, while poor Louise gets only one great aria, Depuis le jour.

Charpentier’s lyrical paeans to Paris almost make the city a fifth principal here. He is also espousing his political convictions about freedom and self-determination and he throws in a bunch of even less fully drawn minor characters, none of whom serve as more than filler. ---Arthur Lazere, culturevulture.net

Once a highly popular opera, Louise, like Mignon, has fallen out of favor in the past half-century, and with that omission from the active repertoire many artists have lost touch with its performance tradition. The best recording is generally held to be the 1956 version with Berthe Monmart, Solange Michel, André Laroze, and Louis Musy (astonishingly, still available on Philips 442082), but the dry, tubby sound does not lend itself well to an opera in which both the richness of orchestration and theatrical atmosphere of each scene need more space around the performers.

Even in the tradition of French operas, the structure and pacing of Louise is highly unusual. It is not conventionally melodic like the operas of Massenet or Saint-Saëns; in fact it never really divides itself into aria-duet-ensemble-chorus in the traditional way, but rather unfolds like a dramatic play with incidental music. If you think even of the most famous extract, Louise’s aria “Depuis le jour,” you will realize that this is not Manon. Just to give one example among many, the daybreak scene at the beginning of act II unfolds slowly, with highly detailed orchestration, just like a real sunrise, the music only becoming gradually animated as more and more characters enter the stage. In fact, it is possibly because the opera is populated much like a real town or city—there are no fewer than 39 solo roles, of which onstage, because of who’s out there at the same time, only three can be doubled—that today’s cost-conscious opera houses shy away from it. Why stage an unpopular opera that requires such a huge cast? It is for this reason, in addition to unfair prejudice leveled at it by pro-Wagnerian critics over the past 130 years, that Les Huguenots is also seldom performed any more. --- Lynn René Bayley, arkivmusic.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega mediafire cloudmailru uplea ge.tt