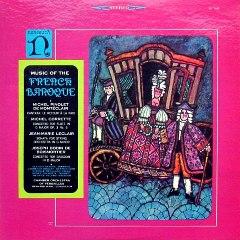

Music of the French Baroque (1965)

Music of the French Baroque (1965)

1 Michel Pignolet de Montéclair: Cantata: Le retour de la paix 17:36

1 air (vivement) - 2 air (tendrement) - 3 air (légèrement) - 4 récitatif - 5 air (lent)

- 6 air léger et doux) - 7 récitatif - 8 air (gai)

Claudie Saneva, soprano

Roger Delmotte, trumpet

Mireille Reculard, cello,

Laurence Boulay, harpsichord

2 Michel Corrette: Flute concerto in G op.3 no.6 9:28

allegro - adagio – allegro

Roger Bourdin, flute

3 Jean-Marie Leclair: Sonata for string orchestra in g 11:55

adagio - allegro ma non troppo - aria – allegro

4 Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Bassoon concerto in D 7:37

allegro - largo – allegro

Maurice Allard, bassoon

Orchestre de Chambre de Versailles

Bernard Wahl – conductor

Michel Pignolet de Montéclair was a French composer, theorist and teacher. He, along with Fedeli, introduced the double bass to The Opera Monteclair. He was a distinguished teacher who held the belief that learning must be fun in order to be effective. He co-founded a music shop in Paris, which became the most successful of its time. Monteclair remained a bachelor throughout his life. He did not produce a great body of work, although he wrote for nearly every genre of the 18th century except keyboard. He was influential in the development of the composer Rameau and was known as one of the most eclectic composers of the generation preceeding Rameau. His stage works are characterized by very clear directions for instruments and singers, perhaps as a result of his desire to control the dramatic color of these elements. His theoretical works are concerned for the most part with the practical application of theory. His ‘Principes de musique’ contains an important section of 18th-century French vocal ornamentation. --- Lynn Vought, All Music Guide

Michel Corrette was the son of an organist, Gaspard Corrette. Details of his life are sketchy and some authorities suggest he may have been born at a date later than that given and at St. Germain-en-Laye. His professional life appears to have begun in 1725 with an appointment as organist at the church in Rouen. Soon after that, he moved to Paris, where he married Marie-Catherine Morize on January 8, 1733.

Most of what is known about his life is a chronicle of his titles, positions, and publications. He was named Grand maître des Chevaliers du Pivots in 1734, became organist to the Grand Prior of France in 1737, and organist of the Jesuit College of Paris in 1750. He received the title Chevalier de l'Ordre de Christ in the same year. In 1759, he gained the position of organist for the Prince of Conti of the Church of St. Marie-Madeleine in 1760, and to the Duc d'Agoulême in 1780.

He was a popular teacher with numerous pupils. He composed motets and masses, secular vocal works, and operas and ballets. He also produced large numbers of arrangements of other music and it is said the music he arranged is much more interesting than the music he composed outright. His best-known works are the Concerts comiques. There are 25 such surviving works in his catalog, based on popular tunes of the day and arranged for three melody instruments and continuo. These are genuine concertos in the standard form of the day, but relatively simple and not musically deep. Other sets of concertos were written on well-known noëls. He wrote light music with programmatic content for amusement, with titles like The Taking of Jericho, The Seven-League Boots, and -- taking advantage of the French enthusiasm for the American Revolution

To musical scholars, he is counted as exceptionally important for leaving nearly 20 method books for various instruments, although they were not always viewed as valuable when Corrette wrote them. While these books are full of humorous stories, they relate to the position of musicians in French and English society and are full of observations about the proper performance of various styles of music. Thus, they aid in understanding the correct performance practices of music of a large part of the eighteenth century. – Joseph Stevenson, Rovi

Jean-Marie Leclair did not settle immediately into his true calling. Born in Lyon in 1697 to a family of lace-makers, he had mastered that craft by the age of nineteen; meanwhile he had met his wife-to-be while both were dancers in the Lyon Opera. In 1722 he was engaged as ballet-master and first dancer in Turin, but by the following year he was in Paris, where the publication of his first set of twelve sonatas for violin and continuo, Op. 1, confirmed his success as a composer and violinist. Apart from a few extended sojourns to patrons in Holland and Spain, Leclair spent the rest of his life in Paris.

The music of Jean-Marie Leclair exemplifies the values and aspirations of the Age of Enlightenment: clarity and rationality; balance, harmony and proportion; and avoidance of excess or exaggeration. From a portrait engraved in 1741, when he was in his mid-forties, Leclair looks out at us with a confident, open gaze; a smile plays about his firmly set mouth; his eyes glint with intelligence. Barring the period dress and the wig, he looks like someone you would gladly sit down with today for conversation, a meal, or a game of chess.

Leclair is generally credited as the founder of the French school of violin playing. He expanded the violin’s technique to include left-hand tremolo (which evolved into what we now call vibrato), double trills, and a meticulously notated variety of articulations; he was renowned for the sweetness of his sound, and for the purity and brilliance of his multiple stops. --- naxos.com

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier. Few eighteenth-century composers earned a personal fortune solely by writing music; Joseph Bodin de Boismortier did, and could claim to be the first Frenchman to sell his talents on the open market. By 1700, the spread of music printing and publishing in Europe, allied to the growth of amateur music-making, made substantial sales of new music possible, and Boismortier seized every opportunity for meeting the popular demand for tuneful, technically simple pieces for a wide variety of vocal and instrumental combinations.

Within a year of arriving in Paris in 1723, his first publications were on sale, and by 1747 had been followed by 102 works. This readiness to provide what the public wanted brought financial success and popularity, but a certain amount of envious comment from the French cultural establishment as well: composers were not supposed to be businessmen! In his Essay on Music, Early and Modern (1750) Jean-Benjamin de La Borde, a contemporary of Boismortier, commented Boismortier ability to turn composition into a lucrative enterprise. The composer's response to La Borde's remarks was brief and to the point: "I make money".

Following common practice of the time, Boismortier frequently scored for alternative instruments -- for example,. recorder, flute, oboe or violin -- thus increasing his sales potential. He was particularly industrious in writing for the flute, and also published a flute method. So fashionable was the instrument in France that the mere imprint "suitable for flute" virtually guaranteed a publishing success. Rustic instruments, such as the musette (bagpipes) and vielle (hurdy-gurdy), were also in vogue, and Boismortier swiftly obliged by providing them with something easy to play.

His output encompassed secular cantatas, motets, songs and four stage works, including an opera, Daphnis et Chloé. He was also an innovator. As the first French composer to adopt the Italian title concerto, he wrote the first French solo concerto for any instrument (in this case the 'cello), as well as a large number of flute sonatas and a set of unaccompanied concertos for three, four, and five flutes.

Boismortier was extremely prolific, but much of what he wrote, though pleasant enough, could hardly be considered significant. At its best it is tuneful, elegant, and by no means naïve. In his Essay on Music, La Borde wrote: "Although [his works] have long been forgotten anyone who desires to take the trouble to excavate them will find enough grains of gold dust there to make an ingot." Today he might have been less grudging, since many of Boismortier's works are still being published, and continue to appeal to players of both modern and period instruments. --- Roy Brewer, Rovi

download:

uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire mega solidfiles cloudmailru filecloudio oboom