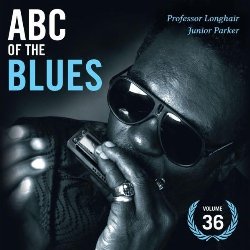

ABC Of The Blues CD36 (2010)

ABC of the Blues CD36 (2010)

CD 36 - Professor Longhair & Junior Parker 36-01 Professor Longhair – Go to the Mardi Gras 36-02 Professor Longhair – In the Night 36-03 Professor Longhair – Hey Little Girl 36-04 Professor Longhair – Walk Your Blues Away 36-05 Professor Longhair – Willie Mae 36-06 Professor Longhair – Professor Longhair Blues play 36-07 Professor Longhair – Misery 36-08 Professor Longhair – Looka, No Hair 36-09 Professor Longhair – Cuttin’ Out 36-10 Professor Longhair – Baby, Let Me Hold Your Hand 36-11 Junior Parker – Feelin’ Good 36-12 Junior Parker – Mystery Train 36-13 Junior Parker – Sittin’ at the Bar 36-14 Junior Parker – Sittin’ at the Window play 36-15 Junior Parker – Sittin’, Drinkin’ and Thinkin’ 36-16 Junior Parker – Dirty Friend Blues 36-17 Junior Parker – Backtracking 36-18 Junior Parker – I Wanna Ramble 36-19 Junior Parker – There Better Be No Feet 36-20 Junior Parker – Fussin’ and Fightin’ Blues

Justly worshipped a decade and a half after his death as a founding father of New Orleans R&B, Roy "Professor Longhair" Byrd was nevertheless so down-and-out at one point in his long career that he was reduced to sweeping the floors in a record shop that once could have moved his platters by the boxful.

That Longhair made such a marvelous comeback testifies to the resiliency of this late legend, whose Latin-tinged rhumba-rocking piano style and croaking, yodeling vocals were as singular and spicy as the second-line beats that power his hometown's musical heartbeat. Longhair brought an irresistible Caribbean feel to his playing, full of rolling flourishes that every Crescent City ivories man had to learn inside out (Fats Domino, Huey Smith, and Allen Toussaint all paid homage early and often).

Longhair grew up on the streets of the Big Easy, tap dancing for tips on Bourbon Street with his running partners. Local 88s aces Sullivan Rock, Kid Stormy Weather, and Tuts Washington all left their marks on the youngster, but he brought his own conception to the stool. A natural-born card shark and gambler, Longhair began to take his playing seriously in 1948, earning a gig at the Caldonia Club. Owner Mike Tessitore bestowed Longhair with his professorial nickname (due to Byrd's shaggy coiffure).

Longhair debuted on wax in 1949, laying down four tracks (including the first version of his signature "Mardi Gras in New Orleans," complete with whistled intro) for the Dallas-based Star Talent label. His band was called the Shuffling Hungarians, for reasons lost to time! Union problems forced those sides off the market, but Longhair's next date for Mercury the same year was strictly on the up-and-up. It produced his first and only national R&B hit in 1950, the hilarious "Bald Head" (credited to Roy Byrd & His Blues Jumpers).

The pianist made great records for Atlantic in 1949, Federal in 1951, Wasco in 1952, and Atlantic again in 1953 (producing the immortal "Tipitina," a romping "In the Night," and the lyrically impenetrable boogie "Ball the Wall"). After recuperating from a minor stroke, Longhair came back on Lee Rupe's Ebb logo in 1957 with a storming "No Buts - No Maybes." He revived his "Go to the Mardi Gras" for Joe Ruffino's Ron imprint in 1959; this is the version that surfaces every year at Mardi Gras in New Orleans.

Other than the ambitiously arranged "Big Chief" in 1964 for Watch Records, the '60s held little charm for Longhair. He hit the skids, abandoning his piano playing until a booking at the fledgling 1971 Jazz & Heritage Festival put him on the comeback trail. He made a slew of albums in the last decade of his life, topped off by a terrific set for Alligator, Crawfish Fiesta.

Longhair triumphantly appeared on the PBS-TV concert series Soundstage (with Dr. John, Earl King, and the Meters), co-starred in the documentary Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together (which became a memorial tribute when Longhair died in the middle of its filming; funeral footage was included), and saw a group of his admirers buy a local watering hole in 1977 and rechristen it Tipitina's after his famous song. He played there regularly when he wasn't on the road; it remains a thriving operation.

Longhair went to bed on January 30, 1980, and never woke up. A heart attack in the night stilled one of New Orleans' seminal R&B stars, but his music is played in his hometown so often and so reverently you'd swear he was still around. ---Bill Dahl, allmusic.com

His velvet-smooth vocal delivery to the contrary, Junior Parker was a product of the fertile postwar Memphis blues circuit whose wonderfully understated harp style was personally mentored by none other than regional icon Sonny Boy Williamson.

Herman Parker, Jr. only traveled in the best blues circles from the outset. He learned his initial licks from Williamson and gigged with the mighty Howlin' Wolf while still in his teens. Like so many young blues artists, Little Junior (as he was known then) got his first recording opportunity from talent scout Ike Turner, who brought him to Modern Records for his debut session as a leader in 1952. It produced the lone single "You're My Angel," with Turner pounding the 88s and Matt Murphy deftly handling guitar duties.

Parker and his band, the Blue Flames (including Floyd Murphy, Matt's brother, on guitar), landed at Sun Records in 1953 and promptly scored a hit with their rollicking "Feelin' Good" (something of a Memphis response to John Lee Hooker's primitive boogies). Later that year, Little Junior cut a fiery "Love My Baby" and a laid-back "Mystery Train" for Sun, thus contributing a pair of future rockabilly standards to the Sun publishing coffers (Hayden Thompson revived the former, Elvis Presley the latter).

Before 1953 was through, the polished Junior Parker had moved on to Don Robey's Duke imprint in Houston. It took a while for the harpist to regain his hitmaking momentum, but he scored big in 1957 with the smooth "Next Time You See Me," an accessible enough number to even garner some pop spins.

Criss-crossing the country as headliner with the Blues Consolidated package (his support act was labelmate Bobby Bland), Parker developed a breathtaking brass-powered sound (usually the work of trumpeter/Duke-house-bandleader Joe Scott) that pushed his honeyed vocals and intermittent harp solos with exceptional power. Parker's updated remake of Roosevelt Sykes's "Driving Wheel" was a huge R&B hit in 1961, as was the surging "In the Dark" (the R&B dance workout "Annie Get Your Yo-Yo" followed suit the next year). Parker was exceptionally versatile -- whether delivering "Mother-in-Law Blues" and "Sweet Home Chicago" in faithful down-home fashion, courting the teenage market with "Barefoot Rock," or tastefully howling Harold Burrage's "Crying for My Baby" (another hit for him in 1965) in front of a punchy horn section, Parker was the consummate modern blues artist, with one foot planted in Southern blues and the other in uptown R&B.

Once Parker split from Robey's employ in 1966, though, his hitmaking fortunes declined. His 1966-1968 output for Mercury and its Blue Rock subsidiary deserved a better reception than it got, but toward the end, he was covering the Beatles ("Taxman" and "Lady Madonna," for God's sake!) for Capitol. A brain tumor tragically silenced Junior Parker's magic-carpet voice in late 1971 before he reached his 40th birthday. In 2001, he was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. --- Bill Dahl, allmusic.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mediafire ulozto gett bayfiles

Zmieniony (Poniedziałek, 19 Sierpień 2019 21:24)