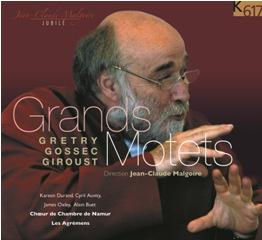

Grétry, Gossec, Giroust - Grands Motets (2006)

Grétry, Gossec, Giroust - Grands Motets (2006)

André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry (1741-1813) Confitebor 1 Confitebor tibi Domine 2’58 2 Magna opera Domini 3’24 3 Confessio et magnificentia 3’20 4 Memoriam 3’36 5 Memor erit 1’22 6 Ut det illis 3’30 7 Fidelia omnia mandata ejus 3’47 8 Redemptionem misit 3’00 9 Sanctum et terribile nomen ejus 4’05 10 Intellectus bonus omnibus 3’22 11 Gloria Patri 4’26 François-Joseph Gossec (1734-1829) Terribilis est locus iste 12 Terribilis est locus iste 1’21 13 Quam dilecta tabernacula tua 4’17 14 Et enim passer inventi 4’13 15 Beati qui habitant 6’38 François Giroust (1738-1799) Benedic anima mea 16 Benedic anima mea 3’20 17 Qui fundasti terram 4’27 18 Qui emittis fontes 3’58 19 Jucundum sit ei 2’49 20 Cantabo Domino 3’30 21 Sit gloria Domini 4’01 Kareen Durand, dessus Cyril Auvity, ténor James Oxley, ténor Alain Buet, basse Choeur de Chambre de Namur Les Agrémens Jean-Claude Malgoire, direction

François Giroust, André-Modeste Grétry and François-Joseph Gossec all belong to the same generation of artists: at the height of their activity between 1760 and 1780, they are among those who contemplated the final flowering of the ‘Baroque’ style in France – Rameau, Mondonville, Dauvergne were still composing – and who introduced to Paris and Versailles the modern inspiration of the ‘Classical’ era.

Yet their careers have little in common. Giroust, perhaps the most unassuming of the trio, was essentially interested in sacred music. Having become sous-maître at the Royal Chapel a year after the death of Louis XV (1775), he went on to compose the majority of his grands motets for that institution. Grétry and Gossec both enjoyed highly successful careers in Paris during the reign of Louis XVI: they made only episodic forays to Versailles, even though Grétry obtained the official post of maître de musique to the queen. He became known chiefly for his opéras comiques, which continued to be performed successfully until the late nineteenth century and were particularly appreciated by Marie-Antoinette. Gossec, for his part, was considered the true father of the French symphony, and was fêted at both the Concert des Amateurs of the Hôtel de Rohan and the celebrated Concert Spirituel. In 1795-6, all three were granted the ultimate accolade of appointment as members of the Music section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in the newly created Institut de France.

Three composers, three styles: if the works of Giroust, Grétry and Gossec flow from the same general aesthetic position – the Classicism of which Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven were to be the chief exponents – it is nonetheless true that their respective manners situate them as the heirs to the three dominant national tendencies of the period.

Giroust, first of all, fights to continue the aesthetic tradition of the French grand motet. Following on from Blanchard and Mondonville, he renewed the genre while still retaining the elements of the French style: his Benedic anima mea conserves rigorous, emphatic declamation, refined ornamentation, five-part choral textures, and a close relationship between the soloists and the choral forces (grand choeur), all features which are vestiges of the Baroque grand motet as conceived by Lalande at the end of Louis XIV’s reign.

Grétry, on the other hand, cannot conceal the Italian influence that was to dominate his output throughout his career: the Confitebor, composed during his period in Italy, owes everything to that country’s great masters, foremost among them Pergolesi whose famous Stabat Mater was then the most universally applauded composition. Thus it takes the form of a string of solo arias occasionally relieved by a chorus, and gives vocal virtuosity primacy over the learned complexities of counterpoint. The three-part string ensemble (first and second violins and bass, without wind instruments) is handled in brilliant and modern fashion: orchestral unisons, tremolos, rushing scales, arpeggios are among the mannerisms taken over from the emerging Mannheim school and abundantly exploited by the likes of Jommelli, Sacchini, and Piccinni in Rome, Naples, and Venice. In his Terribilis est locus iste, Gossec displays an art that has reached its full maturity. The ample formal schemes, skilful modulations and eloquently shaped melodies here evoke the grand German style of Haydn and Mozart as it became established in France in the 1770s.

Bringing together horizons as varied as those of Mondonville, Pergolesi and Haydn, the ‘French Classical style’ of Giroust, Grétry and Gossec is therefore the product of a harmonious synthesis, which took place all the more easily since, during the last twenty-five years of the eighteenth century, Paris became the artistic capital of Europe. In the course of their travels, Piccinni, Sacchini, Salieri, Gluck, Johann Christian Bach and Mozart mingled with each other in Paris and had their masterpieces performed there, speeding up the process which was to lead to the birth of an ‘international style’ around 1785.. ---Editorial Reviews

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega mediafire zalivalka cloudmailru uplea ge.tt