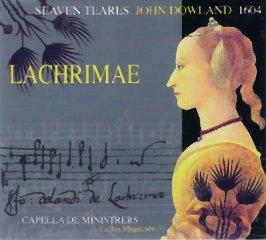

John Dowland - Lachrimae, Or Seven Teares (2006)

John Dowland - Lachrimae, Or Seven Teares (2006)

1. Lachrimae Antiquae 2. Sir John Souch His Galiard 3. Lachrimae Antiquae Novae 4. M. Henry Noell His Galiard 5. Lachrimae Gementes 6. The Earle Of Essex Galiard 7. Lachrimae Tristes 8. M. Nicho. Gryffith His Galiard 9. Lachrimae Coactae 10. M. Giles Hoby His Galiard 11. Lachrimae Amantis 12. M. Thomas Collier His Galiard 13. Lachrimae Verae 14. Capitaine Digorie Piper His Galiard 15. Semper Dowland semper Dolens 16. The King Of Denmarks Galiard 17. Sir Henry Vmptons Funerall 18. M. Bucton His Galiard 19. M. Iohn Langtons Pauan 20. Mrs. Nichols Almand 21. M. George Whitehead His Almand Capella de Ministrers: Carles Magraner - treble viol Jordi Comellas - treble viol, tenor viol Clara Hernández, Lixsania Fernández, Renée Bosch - bass viol Rafael Bonavita - lute Pau Ballester – percussion

If there is any music associated with John Dowland, it is his cycle of pavans which was published in 1604 under the title Lachrimae or Seaven Teares. They reflect the melancholy which seems to have been quite fasionable at the time. They are also thought to be characteristic of the composer himself, as this same publication contains a pavan called Semper Dowland semper dolens. But there is no firm evidence that Dowland himself was a specifically melancholic person. And, in fact, there is more to the Lachrimae than one may think.

It would be a mistake to consider the Lacrymae pavans to be exclusively gloomy. The sixth pavan, Lachrimae Amantis, for instance, "moves firmly away from grief and anger to the tears of love, not those of disappointed or thwarted love, but of blissful radiance", Brian Robins writes in his programme notes. In his preface Dowland himself indicates that the Lachrimae are not intended to revel in melancholy: "And though the title doth promise teares, unfit guests in these joyfull times, yet no doubt pleasant are the teares which musicke weepes, neither are teares shed alwayes in sorrowe, but sometime in joy and gladnesse". Dowland's Lachrymae find their counterparts in other compositions of the time, which also seem to express grief, but have the intention of transcending grief either through faith in God or through music, like these pavans by Dowland. Compositions like these not only expressed sadness, they were also meant to cure people from it. Brian Robins may be right in suggesting the much livelier galliards and almands which are included in this collection, are aiming at further uplifting the spirit of the player or the audience.

Meanwhile, the descending four-note figure with which every of the seven Lachrymae pavans begins, has become a trademark of Dowland, although he seems not to be its composer. Peter Holman has referred to a madrigal by Luca Marenzio from a collection of 1585 where this motif appears. Dowland was a great admirer of Marenzio and aimed at meeting him in Rome when he stayed in Italy, a meeting which never took place. Could this be a kind of tribute to the composer he admired? The motif must have had an immense appeal to Dowland as he used it twice before, first in a pavan for lute, Lachrimae, and then in the song Flow my tears from The Second Booke of Songes (1600).

The galliards and almands all have names which refer to people from Dowland's time, although it isn't always clear who they are or in what way Dowland was connected to them. Many of these are also reworkings of pre-existing pieces, either lute solos or songs.

There is certainly no shortage of recordings of the Lachrimae in the catalogue. But a new recording is welcome if it offers something new or original. As I don't know all recordings available I'm not sure whether the approach of the Capella de Ministrers is original, but I don't consider it a worthwhile addition to the catalogue anyway as it fails to convince me that it is doing Dowland's music any justice.

The trouble starts with the ordering of the pieces. The seven Lachrimae pavans are a cycle, and therefore it is rather unfortunate that in this performance every pavan is followed by a galliard. This way the character of the cycle is severely damaged and it never can have the effect the composer intended. The fact that in the galliards the ensemble is adding percussion does make things even worse. The tempo of the pavans is slowish, but that is something I could live with if the interpretation would do any justice to these pavans, but it doesn't. There is hardly any phrasing: the players go on and on without any breathing space or any interruption. In addition there is hardly any dynamic shading - the dynamics range mostly between mezzoforte and forte - and the sound of the ensemble is rather obtrusive and lacks clarity. The intimate character of Dowland's music is also damaged, probably due to the venue where the recording took place.

Apart from the fact that percussion is really not called for in the galliards and almands it is shocking to notice that the rhythm of many pieces is severely underexposed and sometimes hardly noticeable. A striking example is M. Henry Noel his Galiard, where there is no rhythm at all: it's just a sequence of sound without any structure or shape.

In short: this is simply a bad recording which doesn't do Dowland's music any justice. ---Johan van Veen, musica-dei-donum.org

download: uploaded yandex anonfiles 4shared solidfiles mediafire mega filecloudio nornar

Zmieniony (Wtorek, 11 Luty 2014 17:50)