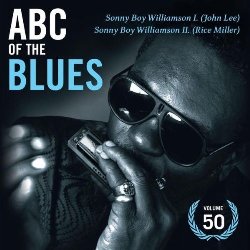

ABC Of The Blues CD50 (2010)

ABC Of The Blues CD 50 – Sonny Boy Williamson I & Sonny Boy Williamson II (2010)

CD 50 – Sonny Boy Williamson I & Sonny Boy Williamson II 50-01 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Black Gal Blues 50-02 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Bad Luck Blues 50-03 Sonny Boy Williamson I – My Black Name Blues 50-04 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Stop Breaking Down 50-05 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Train Fare Blues 50-06 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Check Up on My Baby Blues 50-07 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Ho Doo Hoo Doo play 50-08 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Shake the Boogie 50-09 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Welfare Store Blues 50-10 Sonny Boy Williamson I – Better Cut That Out 50-11 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Don’t Start Me to Talkin’ 50-12 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Keep It to Yourself 50-13 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Fattening Frogs for Snakes 50-14 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Wake Up Baby 50-15 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Your Funeral and My Trial 50-16 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Cross My Heart 50-17 Sonny Boy Williamson II – I Don’t Know 50-18 Sonny Boy Williamson II – All My Love in Vain play 50-19 Sonny Boy Williamson II – Dissatisfied 50-20 Sonny Boy Williamson II – 99 50-21 Sonny Boy Williamson II – The Key (To Your Door)

Easily the most important harmonica player of the prewar era, John Lee Williamson almost single-handedly made the humble mouth organ a worthy lead instrument for blues bands -- leading the way for the amazing innovations of Little Walter and a platoon of others to follow. If not for his tragic murder in 1948 while on his way home from a Chicago gin mill, Williamson would doubtless have been right there alongside them, exploring new and exciting directions.

It can safely be noted that Williamson made the most of his limited time on the planet. Already a harp virtuoso in his teens, the first Sonny Boy (Rice Miller would adopt the same moniker down in the Delta) learned from Hammie Nixon and Noah Lewis and rambled with Sleepy John Estes and Yank Rachell before settling in Chicago in 1934.

Williamson's extreme versatility and consistent ingenuity won him a Bluebird recording contract in 1937. Under the direction of the ubiquitous Lester Melrose, Sonny Boy Williamson recorded prolifically for Victor both as a leader and behind others in the vast Melrose stable (including Robert Lee McCoy and Big Joe Williams, who in turn played on some of Williamson's sides).

Williamson commenced his sensational recording career with a resounding bang. His first vocal offering on Bluebird was the seminal "Good Morning School Girl," covered countless times across the decades. That same auspicious date also produced "Sugar Mama Blues" and "Blue Bird Blues," both of them every bit as classic in their own right.

The next year brought more gems, including "Decoration Blues" and "Whiskey Headed Woman Blues." The output of 1939 included "T.B. Blues" and "Tell Me Baby," while Williamson cut "My Little Machine" and "Jivin' the Blues" in 1940. Jimmy Rogers apparently took note of Williamson's "Sloppy Drunk Blues," cut with pianist Blind John Davis and bassist Ransom Knowling in 1941; Rogers adapted the tune in storming fashion for Chess in 1954. The mother lode of 1941 also included "Ground Hog Blues" and "My Black Name," while the popular "Stop Breaking Down" (1945) found the harpist backed by guitarist Tampa Red and pianist Big Maceo.

Sonny Boy cut more than 120 sides in all for RCA from 1937 to 1947, many of them turning up in the postwar repertoires of various Chicago blues giants. His call-and-response style of alternating vocal passages with pungent harmonica blasts was a development of mammoth proportions that would be adopted across the board by virtually every blues harpist to follow in his wake.

But Sonny Boy Williamson wouldn't live to reap any appreciable rewards from his inventions. He died at the age of 34, while at the zenith of his popularity (his romping "Shake That Boogie" was a national R&B hit in 1947 on Victor), from a violent bludgeoning about the head that occurred during a strong-arm robbery on the South Side. "Better Cut That Out," another storming rocker later appropriated by Junior Wells, became a posthumous hit for Williamson in late 1948. It was the very last song he had committed to posterity. Wells was only one young harpist to display his enduring allegiance; a teenaged Billy Boy Arnold had recently summoned up the nerve to knock on his idol's door to ask for lessons. The accommodating Sonny Boy Williamson was only too happy to oblige, a kindness Arnold has never forgotten (nor does he fail to pay tribute to his eternal main man every chance he gets). Such is the lasting legacy of the blues' first great harmonicist. ---Bill Dahl, Rovi

Aleck “Rice” Miller (died May 25, 1965) was an American blues harmonica player, singer and songwriter. He was also known as Sonny Boy Williamson II, Willie Williamson, Willie Miller, Little Boy Blue, The Goat and Footsie.

Born as Aleck Ford on the Sara Jones Plantation in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, his date and year of birth are a matter of uncertainty. He claimed to have been born on December 5, 1899, but one researcher, David Evans, claims to have found census record evidence that he was born around 1912. His gravestone lists his date of birth as March 11, 1908.

He lived and worked with his sharecropper stepfather, Jim Miller, whose last name he soon adopted, and mother, Millie Ford, until the early 1930s. Beginning in the 1930s, he traveled around Mississippi and Arkansas and encountered Big Joe Williams, Elmore James and Robert Lockwood, Jr., also known as Robert Junior Lockwood, who would play guitar on his later Checker Records sides. He was also associated with Robert Johnson during this period. Miller developed his style and raffish stage persona during these years. Willie Dixon recalled seeing Lockwood and Miller playing for tips in Greenville, Mississippi in the 1930s. He entertained audiences with novelties such inserting one end of the harmonica into his mouth and playing with no hands.

In 1941 Miller was hired to play the King Biscuit Time show, advertising the King Biscuit brand of baking flour on radio station KFFA in Helena, Arkansas with Lockwood. It was at this point that the radio program’s sponsor, Max Moore, began billing Miller as Sonny Boy Williamson, apparently in an attempt to capitalize on the fame of the well known Chicago-based harmonica player and singer John Lee Williamson (Sonny Boy Williamson I). Although John Lee Williamson was a major blues star who had already released dozens of successful and widely influential records under the name “Sonny Boy Williamson” from 1937 onward, Aleck Miller would later claim to have been the first to use the name, and some blues scholars believe that Miller’s assertion he was born in 1899 was a ruse to convince audiences he was old enough to have used the name before John Lee Williamson, who was born in 1914 (this is made somewhat less likely, however, by the fact that Miller was certainly older than Williamson even if one does not accept the 1899 birthdate.) Whatever the methodology, Miller became commonly known as “Sonny Boy Williamson”, and Lockwood and the rest of his band were billed as the King Biscuit Boys.

In 1949 he relocated to West Memphis, Arkansas and lived with his sister and her husband, Howlin’ Wolf (later, for Checker Records, he did a parody of Howlin’ Wolf entitled “Like Wolf”). Sonny Boy started his own KWEM radio show from 1948 to 1950 selling the elixir Hadacol.

Sonny Boy also brought his King Biscuit musician friends to West Memphis: Elmore James, Houston Stackhouse, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, Robert Nighthawk and others, to perform on KWEM Radio.

In the 1940s Williamson married Mattie Gordon, who remained his wife until his death.

Williamson’s first recording session took place in 1951 for Lillian McMurry of Jackson, Mississippi’s Trumpet Records (three years after the death of John Lee Williamson, which for the first time allowed some legitimacy to Miller’s carefully worded claim to being “the one and only Sonny Boy Williamson”). McMurry later erected Williamson’s headstone, near Tutwiler, Mississippi, in 1977.

When Trumpet went bankrupt in 1955, Sonny Boy’s recording contract was yielded to its creditors, who sold it to Chess Records in Chicago, Illinois. Sonny Boy had begun developing a following in Chicago beginning in 1953, when he appeared there as a member of Elmore James’s band. It was during his Chess years that he enjoyed his greatest success and acclaim, recording about 70 songs for Chess subsidiary Checker Records from 1955 to 1964.

In the early 1960s he toured Europe several times during the height of the British blues craze, recording with The Yardbirds and The Animals, and appearing on several TV broadcasts throughout Europe. According to the Led Zeppelin biography ‘Hammer of the Gods’, while in England Sonny Boy set his hotel room on fire while trying to cook a rabbit in a coffee percolator. Robert Palmer’s “Deep Blues” mentions that during this tour he allegedly stabbed a man during a street fight and left the country abruptly.

Sonny Boy took a liking to the European fans, and while there had a custom-made, two-tone suit tailored personally for him, along with a bowler hat, matching umbrella, and an attaché case for his harmonicas. He appears credited as “Big Skol” on Roland Kirk’s live album ‘Kirk in Copenhagen’ (1963). One of his final recordings from England, in 1964, featured him singing “I’m Trying To Make London My Home” with Hubert Sumlin providing the guitar. Due to his many years of relating convoluted, highly fictionalized accounts of his life to friends and family, upon his return to the Delta, some expressed disbelief upon hearing of Sonny Boy’s touring across the Atlantic, visiting Europe, seeing the Eiffel Tower, Big Ben, and other landmarks, and recording there.

Upon his return to the U.S., he resumed playing the King Biscuit Time show on KFFA, and performed around Helena, Arkansas. As fellow musicians Houston Stackhouse and Peck Curtis waited at the KFFA studios for Williamson on May 25, 1965, the 12:15 broadcast time was closing in and Sonny Boy was nowhere in sight. Peck left the radio station and headed out to locate Williamson, and discovered his body in bed at the rooming house where he’d been staying, dead of an apparent heart attack suffered in his sleep the night before.

Williamson is buried on New Africa Rd. just outside Tutwiler, Mississippi at the site of the former Whitman Chapel cemetery. ---last.fm

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mediafire ulozto gett bayfiles

Zmieniony (Wtorek, 16 Lipiec 2019 20:38)