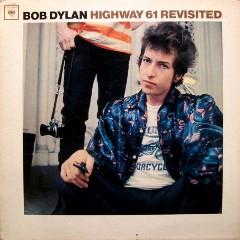

Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

A1 Like A Rolling Stone 5:59 A2 Tombstone Blues 5:53 A3 It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry 3:25 A4 From A Buick 6 3:06 A5 Ballad Of A Thin Man 5:48 B1 Queen Jane Approximately 4:57 B2 Highway 61 Revisited 3:15 B3 Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues 5:08 B4 Desolation Row 11:18 Bass – Harvey Goldstein, Russ Savakus Drums – Bobby Gregg Guitar – Charlie McCoy, Michael Bloomfield Guitar, Harmonica, Piano, Sounds [Police Car Sounds] – Bob Dylan Organ, Piano – Al Kooper Piano – Frank Owens Piano, Organ – Paul Griffin

I never “got” Bob Dylan. I never understood the appeal, and I didn’t know what the big deal was. He was just a guy with a raspy voice and an alright harmonica player. He had his signature voice thing, but besides that, I never knew what made him so revolutionary and worthy of recognition. Maybe living in today’s world, where everyone obsesses over fads and focuses on what’s “in” now, I couldn’t fathom the idea of a timeless artist. Or maybe I’m just not old enough to see any of the artists of my generation become timeless.

I’ve never called myself a Bob Dylan fan, but listening to Highway 61 Revisited for the first time, I liked it. I recognized the first and last songs, and I was surprised by how upbeat and rock-influenced the album sounded. His voice isn’t my usual taste, but it fits with his style and lyrics perfectly. I sensed a political theme in many of his lyrics, but I still didn’t quite understand any of the songs or why Bob Dylan was so celebrated.

Bob Dylan was, and still is, known for his acoustic folk protest songs. Songs such as “The Times They Are a-Changin” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” articulated the political climate of the sixties and voiced the disparity between the younger and older generations. He sang about the abundance of political changes during that time, such as the Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War. Highway 61 Revisited, released in 1965, was Bob Dylan’s first completely electronic album; this means he ditched the solo acoustic guitar and harmonica for a blues inspired rock and roll band on every song except the final “Desolation Row.” His previous album, Bringing It All Back Home, released the year before, contained half acoustic and half electronic songs, but Highway 61 Revisited was the first album where Dylan brought his band with him on tour.

People hated it. They were outraged Dylan would release anything besides his famous acoustic protest solo songs, and when he infamously played “Like a Rolling Stone” at the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965, people booed until they could barely hear the music. The album received many nasty reviews, and people felt he had betrayed his scene. That didn’t make sense to me. I always thought Bob Dylan was universally praised and was considered one of the greatest songwriters of all times; only bad opening bands got booed.

Highway 61 Revisited was Dylan’s first real rock and roll album, and it included direct influences from traditional blues musicians rather than his original folk sounds. The influences are obvious, and Dylan made them obvious. Michael Bloomfield, who played in Paul Butterfield Blues Band, played lead guitar on the album, and many of his lyrics allude to traditional blues artists and songs.

The title Highway 61 Revisited situates the album in America, and some claim that Highway 61 links Minnesota, Dylan’s birthplace, to New Orleans, the birthplace of the blues. Dylan has officially transitioned from folk to blues, at least for now, and he’s not holding back. When people boo, he will play louder and he won’t give in.

Learning about the opening track alone, “Like a Rolling Stone,” I started to understand what everyone was saying. It’s catchy and when Dylan asks, “How does it feel?” it’s no surprise it became a number one hit. However, for the time period, it was revolutionary. “Like a Rolling Stone” is over six minutes long, and its lyrics reject the materialism most of mainstream pop seems to embrace. It’s thought provoking, and although it includes very vivid and specific imagery, the vague and versatile chorus challenges people to question the meaning and satisfaction of their own lives. It’s no wonder The Rolling Stone named it number one on its list of Top 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

Beginning an album with a six minute song is risky, and can risk detracting listeners nowadays, but “Like a Rolling Stone” holds enough power and ferocity to entice the listener. It’s the hit, but the album doesn’t go downhill from there; each song brings something new, whether it’s the power of “Ballad of a Thin Man” or the cheek of “Queen Jane Approximately.” Similar to “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Ballad of a Thin Man” asks “Is this where it is?” He creates a character, unfulfilled and questioning the way he or she has chosen to live, but he obviously directs the questions to the listeners.

Highway 61 Revisited is a transitional album for Dylan, and he’s not apologizing. Musicians evolve and experiment, and for somebody whose career has spanned 50 years and is still continuing, it’s impossible not to change, no matter how much people love his folk music. The lyrics perfectly fit Dylan’s style, whether he plays on his acoustic guitar or with an electronic band. Although Bob Dylan isn’t the greatest vocalist, his voice works with his style, and a more polished vocalist wouldn’t give the lyrics their same validity. Never sounding too raucous and maintaining a laid back ease, Dylan’s lyrics give his songs their ferocity and controversiality rather relying on harsh instrumentals. The sound changed, but his songs still hold their meaning. His lyrics still speak to the ever changing political climate of the sixties, and they challenge people to find their own interpretation. His songs are rooted in their time period, but with themes such as the futility of materialism and superficiality, they are also timeless. ---Marissa Mykietyn, theodysseyonline.com

Bob Dylan:”Jeśli chodzi o to, co było dla mnie przełomem, to musiałbym powiedzieć, że „Like a Rolling Stone”, ponieważ napisałem ją po tym, jak rzuciłem, śpiewanie i granie, i wtedy nagle zorientowałem się, że piszę tę piosenkę, tę historię”. Dylan będąc pod wrażeniem brzmienia takich zespołów jak The Beatles, The Animals czy The Byrds szukał czegoś pełniejszego, rhythm and bluesowego brzmienia połączonego z folkową emocjonalnością. Potrzebne mu było ostrzejsze brzmienie, które nadawałoby znaczenie jego słowom. Wcześniejsza płyta nagrana była na poły akustycznie, teraz Dylan stworzył już cały album elektryczny.

Do studia zaprosił m.in. gitarzystę bluesowego Mike’a Bloomfielda, basistę Harveya Brookesa czy Ala Koopera. Sesja nagraniowa, która miała miejsce w studiu CBS 15 czerwca 1965 roku, przeszła już do legendy kultury pop. Głównym źródłem tej legendy jest wersja podana przez Ala Koopera w jego autobiografii zatytułowanej „Backstage Passes”. Kooper miał zagrać na gitarze, kiedy jednak Dylan przyprowadził ze sobą Bloomfielda zrozumiał, że na gitarze nie zagra. Jednakże w momencie rozpoczęcia nagrania nowej piosenki Dylan postanowił, że będzie potrzebować zarówno fortepianu jak i organów. Kooper zaproponował wtedy, że zagra na organach. Al opowiada, że zmieniał rejestry „jak małe dziecko po omacku szukające kontaktu w ciemnościach”. Dylanowi odpowiadało to brzmienie i bardziej wyeksponował organy. W ten sposób powstało to jedyne w swoim rodzaju połączenie organów i gitary, tak charakterystyczne dla wielu innych utworów Boba.

Nazwa albumu pochodzi od jednej z ważniejszych amerykańskich arterii komunikacyjnych, Autostrady 61. Autostrada ta łączy dom Dylana w Minnesocie z miastami na południu St.Louis, Memphis czy New Orleans, które słynną z muzycznego dziedzictwa. Dylan: ”Autostrada 61 to główna arteria country bluesa. To było moje miejsce we wszechświecie, zawsze czułem, że płynie w mojej krwi”. „Like a Rolling Stone” to otwierający ten album utwór, jest chaotycznym bluesem, pełnym impresjonizmu i intensywnej bezpośredniości. Piosenka odnosi się nie do jednej prawdziwej postaci ale raczej do tego typu kobiety z ówczesnego społeczeństwa, która potyka się, bez celu idzie, niepohamowana przez życie. „Kiedyś przed laty ubierałaś się ładnie/byłaś taka młoda, rzucałaś włóczęgom grosz, czyż nie? ”Wyśmiewałaś każdego kto nie mógł sobie znaleźć miejsca/Teraz nie mówisz już tak głośno/Teraz nie jesteś już tak dumna/I jak się czuje taki ktoś/Kto nie ma domu, nie znany nikomu, wałęsa się jak toczący się kamień”.

Kolejne utwory zostały przyporządkowane nowemu brzmieniu Dylana. I tak szybki, bluesowy „Tombstone Blues” urozmaicił Bloomfield strzelająca gitarą na tle, której kolorowa mieszanka postaci historycznych przechodzi przez słuchacza. „Geometria niewinności, istota życia/sprawia, ze notatnik Galileusza/zostaje rzucony w Dalilę, kusicielkę siedzącą tak bezczynnie samą”. „Król Filistyńczyków” to L.B. Johnson, wysyłający swoich niewolników do dżungli. Również bluesowym, dynamicznym miał być utwór „Phantom Engineer”. Jednakże po wykonaniu nagrania, kiedy zespół poszedł na lunch, Dylan usiadł przy fortepianie i zmienił utwór, tak, że powstała nieco wolniejsza i bardziej sentymentalna opowieść. W rezultacie narodziła się piękna wersja płytowa „It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”. „From A Buick 6” jest bluesem mocno osadzonym w Delcie, hołdem dla takich muzyków jak: Robert Johnson czy Big Joe Williams.

Diabelnie brzmiący fortepian i falujący Hammond opisane przez Koopera jako „muzycznie bardziej wyrafinowane niż cokolwiek innego na płycie”, to w najczystszej postaci protest song wszechczasów, to jedna linijka tekstu, która zmieniła oblicze świata. Przecież wokoło było nowe. Stary, zdegustowany świat wyparty został przez młodzieńcze Lato Miłości. Kontrkultura opanowała cały świat. „Wchodzisz do pokoju z ołówkiem w ręce/Widzisz kogoś nagiego i pytasz: ”Kim jest ten człowiek?”/Bardzo się starasz, ale nie rozumiesz/Co powiesz, kiedy wrócisz do domu/Ponieważ coś tu się dzieje, ale nie wiesz co to jest/Prawda Panie Jones?”. „Ballad Of a Thin Man” jest kolejnym przykładem jak daleko odszedł Dylan od swoich początków. Już nie wystarcza mu tylko gitara i harmonijka. Cały zespół akompaniujący tworzy potężną falę, która podobnie jak tekst utworu rozbija nadbrzeże.

„Rzekł Bóg do Abrahama „Zabij dla mnie syna”/Abraham na to „Człowieku, chyba ze mnie kpisz”/Bóg zaś „Nie”, Abraham „Jak to?”/Bóg „Możesz robić co chcesz Abrahamie”/Lecz następnym razem gdy mnie ujrzysz lepiej uciekaj/No więc, mówi Abraham „Gdzie chcesz, żebym to zrobił”/Bóg odpowiada „Tam na 61 autostradzie”. To historia drogi, slide gitara Bloomfielda daje jej odpowiedni napęd i tworzy bluesowe boogie jak dźwięk maszynki do mięsa.

Płytę Dylan kończy osobliwy akustycznym ponad jedenastominutowym numerem „Desolation Row”. To pełna surrealizmu opowieść, zawierająca aluzje do różnych znanych postaci kultury zachodniej. Niektórych historycznych jak Neron czy Einstein, niektórych biblijnych (Noe, Kain, Abel), niektórych fikcyjnych (Ophelia, Kopciuszek) i niektórych literackich (T.S. Elliot, Ezra Pond).

„Chwała Neptunowi Nerona, Tytanic wyrusza w morze o świcie/Wszyscy krzyczą „Po której jesteś stronie?”/A Ezra Pond i T.S.Elliot walczą na kapitańskim mostku/Między oknami morza, gdzie pływają śliczne rusałki/I nikt nie musi zbytnio rozmyślać o zaułku osamotnionych”. W tej pełnej pokrętnych aluzji piosence na gitarze akustycznej zagrał Charlie McCoy, legendarny muzyk z Nashville. Brzmienie jego gitary przypomina południowo-zachodnią muzykę amerykańską.

Płyta „Highway 61 Revisited” ponownie odkryła rock and rolla w jedyny sposób, który nie został osiągnięty przez następne lata. Nikt nie napisał wcześniej takich tekstów na longplay rock and rollowy. Jednak było jasne, że jest to album rock and rollowy – od łomotu werbla w „Like a Rolling Stone” czy szaleństwa gitary w „Highway 61 Revisited” po majestatyczne brzmienie „Ballad Of a Thin Man” i ekspresję śpiewu Dylana w „Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”.

Powstał wielki album, który przetrwa wszelkie zawieruchy i będzie tkwił na firmamencie wszechświata po wieki. ---Grzegorz Wiśniewski, artrock.pl

download (mp3 @320 kbs):