Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1

Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1

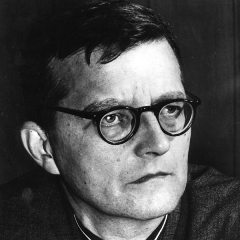

During his long career under the Communists, Dmitri Shostakovich seesawed between being the pride of Russian music and a pariah one step away from the Siberian Gulag. His lowest moments came in 1936, when he was denounced for his seamy opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” (he restored himself to favor with his famous Fifth Symphony), and again in 1948. In that year, Stalin, aging and crazier than ever, attacked musicians, writers, scientists, and scholars: denouncing the most prominent figures to cow the masses. A Party Resolution condemned composers for "formalistic distortions and anti-democratic tendencies alien to the Soviet people." Black lists were drawn up, and heading the composers' list were the names of Shostakovich and Prokofiev.

Dmitri Shostakovich - Violin Concerto No 1 in A Minor

In 1948, Shostakovich had just completed his First Violin Concerto, but locked it away in a desk drawer; this probing and sometimes sarcastic work might seal his doom with the Soviet authorities. With little warning, Shostakovich and other leading Soviet composers found that many of their works that were once praised were now banned. The rationales given were ludicrous; Shostakovich and other composers were forced to listen to long harangues from cultural apparatchiks laden with virtually meaningless terms like “formalism” and “socialist realism.” Despite having sincerely tried to understand these terms for the past two decades, many composers came to the conclusion that social realist works were simply the ones in favor at the moment and formalist ones were not. It would have been laughable if only so much had not been at stake.

Shostakovich and Stalin

After the death of Stalin in 1953, there was a gradual relaxation of the persecution of Soviet artists. By 1955 when the composer was 50, under the more relaxed regime of Nikita Khrushchev, compositions that had been hidden away for fear of disciplinary actions were beginning to emerge. One such was Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1. He revised the score a bit; the premiere was given in Leningrad on October 29 of that year by the illustrious violinist David Oistrakh with the Leningrad Philharmonic under Evgeny Mravinsky, and published as Op. 99.

Mravinsky, Oistrakh and Shostakovich

The Concerto is drawn to the broad proportions of such predecessors as the violin concertos of Beethoven and Brahms, but it is in four movements rather than the usual three (as Brahms had actually intended for his own concerto at first), resembling the form of a symphony more than a concerto, and quite specifically the somewhat unorthodox layout characteristic of Shostakovich's own symphonies.

Dmitri Shostakovich

The opening movement is not a heroic allegro, but a slowich Nocturne. Shostakovich presents us with a supremely beautiful movement, beginning Moderato and sustaining a quiet mood of meditation and memory for quite a long time. The upper registers of the violin are used to their full extent, lyrical and invading, lilting over adept orchestrations. This is profoundly melancholy, even anguished music: an aria for violin with the soloist as a lonely insomniac singing to a sleeping, indifferent world. Darkest woodwinds — clarinets with bass clarinet, bassoon with contrabassoon — paint deep shadows around her. The bleak ending, with tolling harp and celesta accompanying the soloist floating on a fragile high harmonic note, is unforgettable.

Opening movement - Nocturne

The savage second-movement Scherzo is a Fellini-esque circus of the absurd. “Scherzo” means "joke," and this is a harshly sarcastic joke indeed. The ensuing scherzo is a wild, frenetic dance. In this movement, Shostakovich introduces for the first time what would become his musical signature: the notes D-Eb-C-B (in German, these notes are called D-S-C-H, a cypher for Dmitri SCHostokowitsch, the German spelling of Shostakovich’s name). Technically, the first appearance of this figure is D#-E-C#-B, but it later morphs into the more usual form. The inclusion of this motif suggests an autobiographical intent. We cannot know what Shostakovich was thinking when he wrote this passage, but one of Shostakovich’s comments to his friend Maria Sabinina after being forced to read a speech at this time seems to resonate:

“And I got up on the tribune, and started to read out aloud this idiotic, disgusting nonsense concocted by some nobody. Yes, I humiliated myself, I read out what was taken to be ‘my own speech.’ I read like the most paltry wretch, a parasite, a cut-out paper doll on a string!!” This last phrase he shrieked out like a frenzied maniac, and then kept on repeating it.

Not long after the appearance of Shostakovich’s musical signature, the music arrives at a boisterous, klezmer-inspired central episode. The beleaguered soloist flies through a crazed, driven dance of exacting virtuosity.

Hilary Hahn plays Violin Concerto No. 1

As he would in other major works, Shostakovich turned to the Baroque passacaglia form for his powerful F-minor third movement, the Concerto's emotional center. The passacaglia is a repeating melodic-harmonic pattern, usually in the bass. The bass line in this case is a heavy, oppressive figure introduced by the cellos and basses, as horns play pulsing figures and arpeggios above it. Shostakovich's theme, which we hear is 17 measures long and broken into choppy two-measure phrases. Gradually this pattern travels through the orchestra; even the soloist eventually takes it up in fierce double-stopped octaves. After a quieter variation for winds, the soloist enters with an expressive melody. An increasingly tense series of variations follows, until the solo violin takes up the bass line itself before returning to its original melody. The movement concludes with one of the longest and most taxing (both physically and emotionally) cadenzas ever written for a violinist; it is almost a movement in itself and constitutes the soloist's commentary on the entire concerto.

Passacaglia theme

In the concertos of the previous century, cadenzas were normally placed just before the end or at the climax of the first movement. Instead, Shostakovich places his cadenza between movements, making it seem untethered, as if we have passed into some netherworld that is neither here nor there. Suspended in this liminal space, the soloist seems even more alone and isolated. The cadenza becomes faster and more intense as it progresses, recalling ideas from the previous movements, including the DSCH motif. Climaxing with the return of the klezmer theme in the violin’s highest register, the cadenza then accelerates into the finale.

Nicola Benedetti plays Violin Concerto No. 1

Shostakovich titled the last movement “Burlesca,” (Allegro con brio) an indication that fits the music’s darkly comic atmosphere. Its mad, virtuoso fiddle music brings the concerto to an unsettling, but thrilling conclusion. But here the mood seems less bitter than earlier: more a wild folk dance over a driving rhythmic ostinato. Midway, the passacaglia theme makes a brief, mocking appearance in clarinet, horn, and the hard-edged clatter of xylophone. Again, shrill woodwinds dominate this finale, while the soloist hurtles through a non-stop display of virtuosity, culminating in a final acceleration to Presto.

Leonidas Kavakos plays Violin Concerto No. 1

Composed in four movements of symphonic weight, this is a true "iron man" concerto, calling on everything in the violinist's technical arsenal as well as vast physical and emotional stamina. Even the redoubtable Oistrakh begged the composer to give the opening of the finale to the orchestra so that "at least I can wipe the sweat off my brow" after the daunting solo cadenza that concludes the third movement.

Shostakovich and Oistrakh

Because of the delay before its premiere, it is unknown whether or not the concerto was composed before the Tenth Symphony (1953). While the Symphony is generally thought to have been the first work that introduces Shostakovich's famous DSCH motif, it is possible that the First Violin Concerto was actually the first instance of the motif. Shostakovich uses this theme in many of his works to represent himself.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich - Violin Concerto No 1 - David Oistrakh

Last Updated (Tuesday, 07 August 2018 22:16)