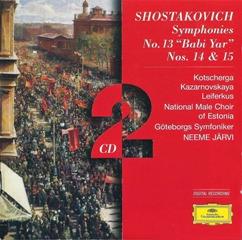

Dmitri Shostakovich - Symphonies Nos.13, 14 & 15 (Neeme Järvi) [1996]

Dmitri Shostakovich - Symphonies Nos.13, 14 & 15 (Neeme Järvi) [1996]

Disc: 1 1. Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141: 1. Allegretto 2. Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141: 2. Adagio - Largo - Adagio (attacca:) 3. Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141: 3. Allegretto 4. Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141: 4. Adagio - Allegretto - Adagio - Allegretto 5. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 1. De profundis 6. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 2. Malagueña 7. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 3. Loreley 8. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 4. The Suicide 9. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 5. On Watch 10. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 6. Madam, look! Disc: 2 1. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 7. At the Sante Jail 2. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 8. Zaporozhye Cossacks' Reply to the Sultan of Constantinople 3. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 9. O Delvig, Delvig! 4. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 10. The Poet's Death 5. Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135: 11. Conclusion 6. Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113 (Babi Yar): 1. Babi Yar 7. Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113 (Babi Yar): 2. Humour 8. Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113 (Babi Yar): 3. At the Store 9. Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113 (Babi Yar): 4. Fears 10. Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113 (Babi Yar): 5. Career Ljuba Kazarnovskaya – soprano Anatolij Kotscherga – bass Sergei Leiferkus - bass Estonian National Male Choir Goteborgs Symfoniker Neeme Järvi – conductor

Symphony No. 13 "Babi Yar". The death of Josef Stalin on March 5, 1953, ushered in an era of freedom for Soviet artists. But, oddly enough, for nearly a decade following the dictator's passing, Shostakovich, one of the chief targets of Soviet censors in the past, wrote nothing of a radical or adventurous nature. In 1962, however, he broke out of his conservative shell and composed his Symphony No. 13, whose expressive language is deeper and more uncompromising than any of his then-recent compositions. Only the unwieldy Symphony No. 4, whose belated premiere took place in 1961, 25 years after its completion, is as challenging and substantive.

Even before the Symphony No. 13's premiere, Shostakovich was in trouble with the Khrushchev regime over it, though not, however, because of his music, but rather because of the texts he chose to set. The work uses five poems by Evgeny Yevtushenko, and it was the first of these in particular, "Babi Yar," from which the symphony derives its subtitle, that created the controversy. It tells of oppression of the Jews in Russia, an injustice Soviets felt the need to deny.

Over the objections of government officials, the premiere of the symphony took place in December 1962. It was a success, but pressures mounted to suppress or modify the work and a second performance had to be canceled. Bowing at last to the wishes of authorities, Yevtushenko and Shostakovich allowed the texts to be attenuated. Another performance took place, with the textual changes, after which the work disappeared from Soviet concert halls for nearly three years.

The Symphony No. 13 is made up of five movements, each having a subtitle pertaining to a Yevtushenko poem: Adagio ("Babi Yar"), Allegretto ("Humor"), Adagio ("In the store"), Largo ("Fears"), and Allegretto ("A career"). The chorus sings in unison or octaves throughout, except for a passage near the end of the third movement. The orchestral forces are sizeable, but Shostakovich's scoring tends to be sparing throughout, although there are outbursts of considerable power in several places.

The first movement is dark and dramatic, morbid and harsh. This bleak panel, with the bass soloist prominent throughout much of its duration, is an atmospheric and powerful setting of Yevtushenko's texts. The second movement is a Scherzo, and its "Humor" is often tart and brash.

The last three movements are continuous. The text of "In the store" praises the ordinary working woman. Shostakovich's music is subdued and dark throughout most of the movement, painting a bleak picture of life (which Soviet officials also could not have found much to their liking). The riveting climax in this section comes when the chorus sings (about women), "To shortchange them is shameful...." The austere and dark fourth movement deals with fears, as the chorus starts off whispering the word, effectively summoning a fearful atmosphere. The last movement, which offers text praising those with integrity in their careers, begins with an attractive, slightly sad waltz, although the mood throughout is brighter than in any previous panel. The ending is quiet, with the waltz turning gossamer, almost mystical.

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, this symphony gained considerable popularity both in the concert hall and on recordings. A typical performance of it lasts from about an hour to nearly 70 minutes. --- Robert Cummings, Rovi

Symphony No. 14 for soprano, bass, strings & percussion, Op. 135. In Testimony, by Solomon Volkov, Shostakovich is quoted, "Fear of death may be the most intense emotion of all....[However], death is not considered an appropriate theme for Soviet art, and writing about death is tantamount to wiping your nose on your sleeve in company....I wrote a number of works reflecting my understanding of the question, and as it seems to me, they're not particularly optimistic works. The most important of them, I feel, is the Fourteenth Symphony; I have special feelings for it....[People] read this idea in the Fourteenth: 'Death is all-powerful.' They want the finale to be comforting, to say that death is only the beginning. But it's not a beginning, it's the real end, there will be nothing afterward, nothing...."

The musical vocabulary is his most advanced since two early and cacophonous cantata-symphonies: No. 2 (To October) and No. 3 (The First of May). He himself chose texts in Russian translations. It is scored for vocalists, strings, and percussion. Although basically diatonic and texturally transparent, the writing in No. 14 is recurringly atonal, with violent outbursts, and an implicit repudiation of "socialist realism." The vocal line suggests accompanied recitative or declamation, even Sprechstimme.

"De Profundis" (García Lorca) for bass. In memory of "the hundred lovers" who died in the Spanish Civil War, a bleak theme winds, while the voice declaims over a contrabass drone.

"Malagueña" (García Lorca) for soprano. A fast and frightening depiction of Death's coming and going. Castanets and a whip-crack lead without pause to --

"Loreley" (Apollinaire, "after Clemens Brentano") for soprano and baritone. A dialogue between the legendary nymph and a smitten Bishop, who seeks to save her soul, but loses it to the Rhine.

"The Suicide" (Apollinaire) for soprano. Repetitions in the text engender music that doubles back on itself hypnotically.

"Les Attentives One" (Apollinaire) for soprano. About incest and imminent death, with a macabre rhythm on tom-toms and xylophone that creates hysteria, leading to --

"Les Attentives Two" (Apollinaire) for soprano and bass. "Madame, you've lost something." "My heart, nothing important." An ostinato on xylophone accompanies the words "It is here I snap my fingers...."

"In the Santé Prison" (Apollinaire) for bass. The solitary despair of "Lazarus entering the tomb instead of coming forth as he did," with a long, eerie, pizzicato interlude.

"Reply of the Zaporozhean Cossacks to the Sultan of Constantinople" (Apollinaire) for bass. They revile a monarch "more criminal than Barabbas...fed on garbage and dirt...."

"O Delvig! Delvig!" (Küchelbecker) for bass. Addressed to poet-comrade Anton Delvig, this touchingly lyrical lament from prison contains the only ray of light in the work. There is a string epilogue before --

"The Poet's Death" (Rilke) for soprano. A winding musical line recalls "De Profundis" while the singer contemplates the corpse.

"Conclusion" (Rilke) for soprano and bass. In unison, the soloists sing over castanets and string pizzicatos of Death's immensity. It ends on a densely dissonant chord. --- Roger Dettmer, Rovi

Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141 Shostakovich's Symphony No. 15 differs in several substantial ways from his other late symphonies. The Eleventh (1957), subtitled "The Year 1905," and Twelfth (1960), subtitled "The Year 1917," are both programmatic and relate to the political and historical events associated with the year in the title. The next two symphonies have sung texts, with the Thirteenth (1962), for bass, chorus, and orchestra, carrying the subtitle "Babiy Yar" (texts by Yevtushenko), and the Symphony No. 14 (1969), for soprano and bass soloists and chamber orchestra, not really a symphony but a collection of songs based on texts by Lorca, Apollinaire, Küchelbecker, and Rilke.

With the Symphony No. 15, Shostakovich's last foray in the genre, the composer at last returned to the purely instrumental and non-programmatic realm, which, one could argue, he had not revisited since the 1939 Symphony No. 6. While it is true that the Symphonies 8, 9, and 10 carry no official program, the first two are clearly associated with the war (the Ninth is a victory celebration), and the Tenth allegedly contains a portrait of Stalin in its second movement. But the Symphony No. 15 inhabits a purely emotional and intellectual plane, quite removed -- as far as we know -- from the world of politics and history. Yet it is generally agreed that the work is autobiographical, not in the sense that it depicts specific events, but rather that it expresses reflections on the past.

The Fifteenth is also unique in that it is lightly scored throughout, certainly the leanest of the composer's purely instrumental symphonies. Shostakovich had moved in this direction with the Symphony No. 14 and had found increasing difficulty in writing in the late 1960s, owing to a nervous-system disorder -- brittle-bone poliomyelitis -- that gradually crippled his right hand, making simple tasks problematic and rendering the process of scoring complicated orchestral works an extremely grueling task. The Symphony No. 15 was premiered on January 8, 1972, with the composer's son Maxim conducting. A typical performance of the work lasts from 40 to 45 minutes.

The work is divided into four movements: 1) Allegretto, 2) Adagio - Largo - Adagio, 3) Allegretto, and 4) Adagio - Allegretto. It stands apart from the composer's other symphonies in its quotations and near-quotations from compositions by others and by Shostakovich himself. The symphony is, in fact, chock full of these quotations. The first movement, for example, quotes the famous (Lone Ranger) theme from Rossini's William Tell overture. The Fate motif from Wagner's Ring cycle and themes from Siegfried and Tristan und Isolde appear in the finale. There are near-quotations from Tchaikovsky and Mahler, and Shostakovich alludes to themes in some of his earlier symphonies.

The first movement, originally subtitled "The Toyshop," has a childlike atmosphere to its playfulness, yet at times sounds under the spell of dark and cynical forces. The second movement is long and enigmatic, having a funereal mood for much of its duration and climaxing in an outburst of what is clearly anger or frustration. The third movement is the shortest in the work (about four minutes) and is bitingly satirical, even nose-thumbing. The finale contains the most cryptic and perhaps most profound music in the work. Because it, too, appears to express the composer's thoughts on death, many have concluded that the autobiographical elements in the work are expressed in a sort of cradle-to-grave story, the first movement representing childhood and the finale the composer's final years and imminent passing. --- Robert Cummings, Rovi

download: uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire solidfiles mega zalivalka filecloudio anonfiles oboom

Last Updated (Friday, 09 May 2014 10:35)