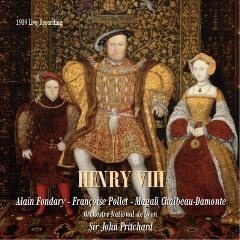

Camille Saint-Saëns - Henry VIII (1989)

Camille Saint-Saëns - Henry VIII (1989)

Disc One [1] Overture [2] - [7] Act One - Scenes 1 - 6 [8] Entr'acte [9] - [15] Act Two - Scenes 1 - 7 (begin.) Disc Two [1] Act Two - Scene 7 (concl.) [2] Act Three [3] Act Four - 1st Tableau [4] Act Four - 2nd Tableau Introductions: [5] to Act One [6] to Act Two [7] to Act Three [8] to Act Four Henry VIII, roi d'Angleterre - Alain Fondary Anne de Boleyn - Magali Chalbeau-Damonte Catherine d'Aragon - Francoise Pollet Le duc de Norfolk - Patrick Meroni Don Gomez de Feria - Christian Lara Earl de Surrey - Daniel Gomez Vallejo Lady Clarence - Franasoise Viran Garter Freddie Bense - Michel Denonfoux Chœurs des Opéras du Rhin et de Montpellier Orchestre philharmonique de Montpellier Sir John Pritchard – conductor

When, in his ''Letter from France'' in the December issue, Andre Tubeuf mentioned the production in Compiegne of Saint-Saens's Henry VIII, I pricked up my ears and wondered whether a recording would be forthcoming—for this work, though very rarely heard, is not only written with outstanding skill (there are several big ensembles with anything up to 14 vocal parts) and some thematic distinction, but has a strong dramatic libretto with firm characterization. Unlike many operas, it doesn't play ducks and drakes with historical events (though it telescopes them a bit), even if it superimposes on them a story of Anne Boleyn having had an affair abroad with the Spanish ambassador at Henry's court; and having been designed for the Paris Opera, it includes a ballet and a big spectacular scene of Catherine of Aragon's trial and Henry's proclamation of himself, after his excommunication, as head of the Anglican Church.

Henry VIII was very well received at its premiere in 1883 and was widely taken up in several countries to the end of the century, and its revival now is much to be welcomed. With fine moments such as the duet between Henry and Anne and that between Anne and Gomez, Catherine's trial scene and her dying lament, and a quartet right at the end, this is still, despite the weaknesses in the performance outlined above, an opera to savour.' --- Lionel Salter, gramophone.co.uk

Although it remained a somewhat marginal work in the operatic repertoire for most of the twentieth century, Camille Saint-Saëns' operatic version of Shakespeare's Henry VIII enjoyed considerable success in the years following its premiere in March 1883. Despite the work's respectable runs in international venues, however, Saint-Saëns felt that the opera deserved a better reception. "How a work like this is not in the repertory everywhere," Saint-Saëns wrote to his publisher in 1909, "that is what I refuse to understand." The composer would have been pleased to observe the handful of revivals the work enjoyed in the 1980s and 1990s; likewise, contemporary audiences would find much to enjoy in this work, in which a powerfully dramatic narrative provides a suitable vehicle for Saint-Saëns' sophisticated compositional voice. The opera, on a libretto by Pierre Léonce Détroyat and Paul Armand Silvestre (with several alterations and a few extensive additions by the composer), tells the story of Henry VIII's infamous rise to power in the beginning of the sixteenth century: his abandonment of Queen Catherine d'Aragon for Anne Boleyn, his subsequent confrontation with the Pope and the Roman Church, and finally, his (and his country's) rejection of Rome's authority. In an effort to evoke the story's historical context, Saint-Saëns researched English music from the period and incorporated several tunes into his score. The Prelude, for example, contains a number of English, Scottish, and Irish folk melodies, while the nationalistic bent of Henry's triumphant tirade against the Pope at the end of Act III is underscored by a forgotten air Saint-Saëns discovered in the library at Buckingham Palace. Still, it is drama rather than historical authenticity that drives the work. Cast in four acts, the work unfolds at a careful pace, with the various intertwining strands of the drama -- romantic, religious, political -- maintaining a constant tension until the ominous conclusion. Saint-Saëns repeatedly stated that he valued emotion and expression above all, and took particular pride in such emotionally charged scenes as the love duet between Henry and Anne in Act II and the quartet at the end of the opera's last act, in which Henry confronts the dying Queen Catherine, her replacement Anne (whose loyalty the king has begun to question), and Anne's former suitor Don Gomez. In the end, all succumb to the king's heavy hand. --- Jeremy Grimshaw, Rovi

download (mp3 @320 kbs):