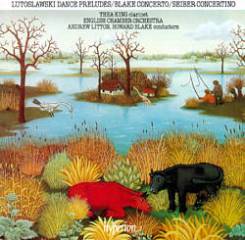

Lutoslawski Seiber Black – Clarinet Concertos

Lutoslawski Seiber Black – Clarinet Concertos

Dance preludes [9'17] Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994) 1 Allegro molto [1'01] 2 Andantino [2'27] 3 Allegro giocoso [1'11] 4 Andante [3'06] 5 Allegro molto [1'32] Concertino for clarinet and string orchestra [15'11] Mátyás Seiber (1905-1960) 6 Toccata (Allegro) [2'38] 7 Variazioni semplici (Andante) [3'39] 8 Scherzo (Allegro) [2'45] 9 Recitativo (Introduzione) (Rubato) [2'55] 10 Finale (Allegro) [3'14] Clarinet Concerto [21'31] Howard Blake (b.1938) 11 Invocation: Recitativo - Moderato, molto deciso [7'51] 12 Ceremony: Recitativo - Lento serioso [7'12] 13 Round dance: Vivace [6'28] Thea King - clarinet English Chamber Orchestra Andrew Litton – conductor (1-10) Howard Blake – conductor (11-13)

In the years immediately following the end of the Second World War, Poland’s musicians and film-makers suddenly blossomed in a remarkable resurgence of artistic independence. But the Communist regime demanded music that was ‘accessible’ and folkloristic, requirements that many Polish composers, Witold Lutoslawski prominent among them, found restrictive, though they managed to conform without compromising their principles. The Dance Preludes are a product of that difficult period and they remain one of Lutoslawski’s most popular works.

Originally written in 1954 for clarinet and piano, Lutoslawski subsequently made two orchestral versions. One closely adheres to the original with the clarinet as soloist; the other, made in 1959 for a larger group, breaks up the solo line and shares it between several instruments. The earlier of these two orchestral versions, the one recorded here, dates from 1955 and was premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1963 with Gervase de Payer as soloist and Benjamin Britten conducting the English Chamber Orchestra. In addition to the strings, harp, piano and percussion were added to the orchestra.

All five movements are based on Polish folk dance rhythms if not actual folk tunes. Lutoslawski has not identified them but they follow the general dictum that ‘the tempo of Polish folksongs changes almost from bar to bar’. The first, led in with a downward arpeggio in crotchets on the clarinet, is a jerky dance, almost wholly staccato. It centres round E flat and varies between 2/4 and 3/4. The second, a flowing Andantino alternating between 9/8 and 6/8, is based on B flat minor tonality with a quicker central section heralded by the quiet rattle of the tambourine.

No. 3, a kind of scherzo, alternates between 2/4 and 3/4 with 4/4 making an appearance near the end. Jagged acciaccaturas give the music a wild, abandoned character, and fast, high-register passages for the soloist suggest the sharp tone of the E flat clarinet favoured by many Polish folk musicians.

No. 4, another reflective piece, this time in 3/4 and 3/2, is introduced by a quiet pizzicato on the doublebass punctuated by a few low flourishes from the piano. The melody, concentrated within the interval of a fifth, is relatively simple and makes much use of repeated notes.

The last movement, a strongly accented dance centring round E flat, is the most complex metrically speaking – a combination of 2/4, 5/4, 3/4, 4/4, and finally 6/4 signatures, with the clarinet being offered alternative passages that run counter to the rhythm of the orchestra. There are hints of bagpipes, and the jolly atmosphere, rising to a wild climax, perhaps suggests a village wedding.

Mátyás Seiber was one of that distinguished group of European composers (others were Roberto Gerhard and Egon Wellesz) who sought refuge in Britain from Nazi tyranny. Seiber, a pupil of Kodály in Budapest, brought with him his Hungarian heritage and a love of jazz as well as an awareness of the music of his most distinguished contemporaries, Bartók and Hindemith – and, to a lesser degree, Schoenberg. All these influences eventually became distilled into a personal style whose further development was cruelly cut short on 24 September 1960 by a fatal car crash in the Kruger National Park during a visit to South Africa.

I am indebted to Thea King for the information that the Concertino was sketched during a train journey from Frankfurt to Budapest in 1926. The work began life as a quintet titled Divertimento for clarinet and string quartet. Its composition occupied Seiber on and off until 1928 and was his only major composition during that period. The present version for clarinet and string orchestra dates from 1951.

In common with many of his contemporaries at the time, Seiber became converted to neoclassicism, but Hindemith’s version of it rather than Stravinsky’s, and the Concertino reflects this preoccupation. It is possible to find in the opening Toccata some of the rhythmic elements associated with trains – running quavers punctuated by octave interjections suggesting wheels, rails and points, but the simile ought not to be taken too far. The Toccata develops into a lively contrapuntal exchange between soloist and orchestra in a modified sonata form with a brief development and the first subject reappearing in reverse order in the recapitulation.

The ‘Variazioni semplici’ is, as its title implies, a brief set of variations on a simple but endearing melody whose outlines evoke Hungary. The Scherzo, a witty but slightly acidic ‘joke’, obliquely reminds us of Seiber’s long-term interest in jazz, though the slap-tonguing demanded of the clarinettist has little to do with that beloved by the Ted Lewises and Wilton Crawleys in the New York of the 1920s. The Recitativo, subtitled ‘Introduzione’ (presumably to the finale) is another folky piece, full of atmosphere and coloured by rapid arpeggios on the clarinet, reminiscent of Bartók’s ‘night music’. Bartók, with Kodály, again comes to mind in the rapid finale, a dance whose outlines call up many such in the works of those two great collector-composers. A coda, pierced by shrill exclamations from the clarinet, again hints at that train journey, or at least its arrival at the Keleti terminus in the Hungarian capital.

Howard Blake was born in London in 1938, but grew up in Brighton. At eighteen he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music in London where he studied piano with Harold Craxton and composition with Howard Ferguson. Then, during the next ten years, he proved himself a highly versatile, all-round musician, working in London as a pianist, conductor and orchestrator, but especially as a composer. In 1971 he left London to live in a watermill in Sussex, and started to forge a personal style of composition – rhythmic, contrapuntal, and above all melodic. Since then there has been a steady stream of works in many different forms: a Divertimento for cello and orchestra, the Clarinet Concerto, a Piano Quartet, Sinfonietta for brass, song cycles, a comic opera, piano music, and the large-scale choral and orchestral work Benedictus which has been given many major performances including the Three Choirs Festival 1987, Westminster and Canterbury Cathedrals, and Kings College, Cambridge, in 1988.

Howard Blake’s Barbican concerts for children enjoyed a huge success, featuring his music for The Snowman with its much-loved song ‘Walking in the Air’. Howard Blake has also composed widely for ballet, television, the cinema and the theatre. He lives once again in London and most of his music is now published by Faber Music.

The Clarinet Concerto was commissioned by Thea King and first performed by her at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London in June 1985, with the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by the composer. A nine-bar recitative leads to the first movement, ‘Invocation’, which develops a mysterious, syncopated theme in G minor. A horn note dies away to a second recitative which leads to the slow movement, ‘Ceremony’, a hushed cantilena using the clarinet’s capacity for sustained lyricism. The third movement uses its capacity for rapid passagework in the form of a restless but exuberant ‘Round Dance’ – an accompanied cadenza returning to the recitative material from the beginning of the work and confirming the strong feeling of the piece as being in one movement.

download: uploaded 4shared ziddu mediafire hostuje anonfiles gett