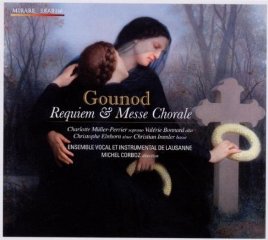

Gounod - Requiem & Messe Chorale (Corboz) [2011]

Gounod - Requiem & Messe Chorale (Corboz) [2011]

Messe de Requiem en ut Majeur, pour 4 solistes, chœur mixte et orchestre 1. Introït & kyrie 6:11 2. Dies Irae 15:13 3. Sanctus 0:47 4. Benedictus 4:12 5. Pie Jesu 3:43 6. Agnus Dei 6:18 Messe Chorale en Sol mineur, avec orgue d'accompagnement et grand orgue 7. Introït 1:15 8. Kyrie 3:27 9. Gloria 5:30 10. Credo 7:38 11. Sanctus 2:00 12. Benedictus 2:14 13. Agnus Dei 4:31 Charlotte Müller-Perrier – soprano Valérie Bonnard – alto Christophe Einhorn – tenor Christian Immler – bass Marcelo Giannini – organ Ensemble Instrumental de Lausanne Michel Corboz - conductor

At first blush, it seems almost as improbable that Gounod should have written a Requiem as it does that Saint-Saëns should have written one. But Gounod did, and so did Saint-Saëns. On record, at least, both have fared poorly in both number and performance.

André Charlet, conductor and note author of the only other recording of Gounod’s Requiem I have (Claves 50-9326), paints a melodramatically macabre picture of the composer’s final hours: “On the morning of 15 October 1893, Gounod, although feeling fatigued, went to church with his faithful companion Henri Büsser. After lunch he sat down to put the finishing touches on the piano arrangement of the exquisite Benedictus. His wife found him with his head ‘held up by his pipe resting on the table,’ bent over the open score of the Requiem. Gounod never regained consciousness; he died three days later on the morning of 18 October with a crucifix in his hands.”

The notes to this new version of Gounod’s Requiem partially contradict Charlet’s notes, and the discrepancy is no small matter. Michel Daudin, who authored the current album’s notes, states that Gounod began work on the Requiem in 1889 in response to the devastating death of his five-year-old grandson, Maurice, and that he put the word “fin” to the foot of his manuscript on Palm Sunday, 1891. That’s two years before Charlet dates the incident of Gounod falling unconscious over his uncompleted score.

The two accounts do manage to jibe in the end, however, for Daudin notes that Gounod continued revising the Requiem up until the October 15, 1893, date reported by Charlet. But Daudin, with even more melodramatic flair than Charlet, adds his own embellishment to the story: “On October 15, Gounod was playing and singing passages of his Requiem at the piano when he had a fit of apoplexy. Though out of breath, he still tried to continue singing the duet from the Benedictus with his daughter, then he carefully put the manuscript away. In the afternoon he was felled by a stroke and lost consciousness. He never emerged from the ensuing coma and died in the small hours of 18 October.”

There’s nothing in Daudin’s telling of the story about Gounod’s wife finding him slumped unconscious over his manuscript, his head resting on his pipe. And there’s nothing in Charlet’s story about Gounod having a stroke while duetting with his daughter and rising up to put his manuscript away before slipping into a coma. So I’m inclined to believe that both stories are rather fanciful imaginings of actual events, and that we shall never know the exact details because, as I’m fond of saying, “CNN wasn’t there.”

Let me say straight away that if you have the Claves recording of the Requiem with Charlet, this new one duplicates it in using the same arrangement of the piece prepared by Henri Büsser for vocal soloists, mixed chorus, and an instrumental ensemble of string quartet, double bass, harp, and organ. Gounod’s original score called for full orchestra, but the composer made a number of his own arrangements for various combinations of singers and instruments. Büsser’s version, chosen by both Charlet and Corboz, seems by general agreement to be the best of the lot. Lest there be any confusion between the two recordings, however, I should also add that each pairs the Requiem with a different Mass. Charlet includes Gounod’s early Mass No. 2 in G Major, op. 1, of 1846; while Corboz gives us the Gregorian chant-based Choral Mass in G Minor, circa 1880, but of firm date uncertain.

Though Gounod is today linked almost exclusively to opera, thanks mainly to Roméo et Juliette and Faust , he was in fact a deeply religious man who, like Liszt, came very close to joining the priesthood and taking holy orders. He immersed himself in the study of 16th-century polyphony, with special attention paid to the masses of Palestrina; unusual perhaps for a 19th-century French composer, he came to revere the keyboard works of Bach, proclaiming the Well-Tempered Clavier “the law to pianoforte study … the unquestioned textbook of musical composition.” Who has not heard Gounod’s meltingly beautiful Ave Maria , a descant set over the C-Major Prelude from Book 1 of Bach’s WTC ? In fact, it wasn’t an opera but a Mass that brought Gounod his first public acclaim in 1855, the Messe Solennelle , aka Saint Cecilia Mass , and throughout his life, he continued to write music based on religious subjects.

Today, the extent of Gounod’s sacred works is little appreciated, their having been eclipsed by his operatic efforts. But this was not always the case. Saint-Saëns declared that Gounod would be remembered principally for his religious music; indeed, his masses, sacred oratorios, and motets far outnumber his operas. Daudin’s note even claims that there are three more Requiem masses in addition to the one on this CD.

Mostly avoiding the theatrical drama of sinners facing their Maker and souls condemned to the eternal fires of Hell—there’s no Berlioz or Verdi here—Gounod’s Requiem is often compared to that of the very popular, almost exactly contemporaneous setting by Fauré in its comforting and non-judgmental tone. No deity could fail to be moved, for example, by Gounod’s exquisitely beautiful Benedictus, which sets a duet for solo soprano and tenor against the chorus. But I’d have to say that in terms of musical style and vocabulary Gounod’s Requiem is closer to Saint-Saëns’s setting of the text, if you’re familiar with that score, than it is to Fauré’s.

Overall, Corboz is a bit slower than Charlet, and his soloists and choristers sound somewhat more devotional, or perhaps beatific is the word I’m looking for. Corboz also benefits from a more pitch-perfect vocal quartet and a better recording, made at La Ferme de Villefavard, a hall constructed in 2002 in the Limousin region of France. I had occasion to mention the exceptional acoustics of this venue in a review of a Brahms piano recital by Adam Laloum, also on Mirare.

Before rejecting Charlet in favor of Corboz out of hand, however, I would remind the reader that the coupling is not the same. Charlet leads a Mass in G Major for male chorus and organ; Corboz leads a Mass in G Minor for mixed chorus with organ accompaniment based on plainchants he heard at the Benedictine monastery in Solesmes. It’s an interesting work, if not a very even or consistent one, with some movements transporting one back to the 16th-century Flemish school of sacred polyphony, while other movements alternate between a 17th-century Italian madrigal style and an 18th-century Bach-like motet style. It’s as if Gounod was trying out all of the crayons in his box.

If you’re a collector of Requiem masses, you will find none more appealing than Gounod’s, and this wonderful new performance and recording of it is most enthusiastically recommended. ---Jerry Dubins, arkivmusic.com

download: uploaded anonfiles yandex 4shared solidfiles mediafire mega filecloudio