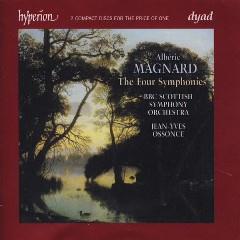

Albéric Magnard – The Four Symphonies (2009)

Albéric Magnard – The Four Symphonies (2009)

Symphony No 1 In C Minor Op 4 31:07 1-1 Strepitoso 10:03 1-2 Religioso, Largo - Andante 9:04 1-3 Presto 3:37 1-4 Molto Energico 8:23 Symphony No 2 In E Major Op 6 36:04 1-5 Ouverture: Assez Animé 9:59 1-6 Danses: Vif 5:26 1-7 Chant Varié: Très Nuancé 12:11 1-8 Final: Vif Et Gai 8:28 Symphony No 3 In B Flat Minor Op 11 37:33 2-1 Introduction Et Ouverture: Modéré - Vif 12:23 2-2 Danses: Très Vif 6:08 2-3 Pastorale: Modéré 8:21 2-4 Final: Vif 10:41 Symphony No 4 In C Sharp Minor 35:40 2-5 Modéré 10:44 2-6 Vif 4:48 2-7 Sans Lenteur Et Nuancé 12:21 2-8 Animé 7:47 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Jean-Yves Ossonce - conductor

Though they are relative rarities in the concert hall the symphonies of Albéric Magnard have been represented quite reasonably in the recording studio. I seem to recall a complete cycle for EMI by Michel Plasson and the Toulouse Capitole Orchestra a good few years ago. More recently Thomas Sanderling set down the symphonies for BIS, coupling the Second and Fourth, in performances that attracted a mixed reception on MusicWeb International: see review by Peter Graham Woolf and a second appraisal by Reg Williamson. Sanderling’s BIS pairing of the First and Fourth Symphonies (50097) does not appear to have been reviewed here. The complete cycle has recently been reissued by Brilliant Classics, which was noted by Patrick Waller.

Rob Barnett reviewed the present recordings on their original appearance as a pair of separate discs and he was impressed. I haven’t had the time yet to listen in any detail to my own recently-acquired copy of the Sanderling cycle on Brilliant Classics, though I have done a very limited amount of dip testing. I would in no way claim to have made a detailed comparison between the Sanderling and Ossonce versions. Issues of interpretation aside, one can point to three overall presentational differences between the respective cycles. The generally longer durations of Sanderling’s recordings mean that his cycle spills over onto three CDs, with Symphonies 2 and 4 each occupying a single disc. However, at the Brilliant Classics price there’s probably little to choose between the rival versions in terms of cost. The recorded sound for each set is very pleasing though I’d say that the Sanderling versions are a bit more closely recorded and Ossonce’s recordings give a bit more space around the orchestra. One thing that’s definitely in favour of this Hyperion reissue is the excellent notes by composer Francis Pott, whose own music I’ve come to admire greatly. The note accompanying the Sanderling set, which may be an edited version of the original BIS notes, is a perfectly serviceable general introduction to the composer and to the works but Pott’s essay is on a very different plane, offering depth of knowledge and analysis and much perceptive comment.

Magnard, who began his formal musical studies only in his twenties, became a close associate of Guy-Ropartz, who introduced him to d’Indy, whose pupil he became, and to Franck. Magnard’s own music is clearly influenced by that school of composition, as you’d expect, and his four symphonies are firmly in the late nineteenth-century French romantic tradition.

Writing of the first movement of the First Symphony, Francis Pott comments that it “arguably suffers from an excess both of alternatives to follow up and of orchestral colours in which to dress them.” One cannot but agree though I’d suggest that the comment could fairly apply to the whole work. It seems to me that much of Ossonce’s success in this symphony lies in keeping the music moving forward and in achieving clarity of balance within the rich orchestration. He brings excellent drive to the first movement and the second, marked “Religioso” is deeply felt. The BBC Scottish players, who acquit themselves admirably throughout the work, play the vivacious scherzo with panache. The finale has energetic passages though Magnard is frequently unable to resist the temptation to dawdle in pleasant by-ways. On the evidence of the limited comparisons I’ve been able to make I’d say there’s little to choose between Ossonce and Sanderling in this symphony.

The Second, Francis Pott avers, “marks a considerable advance (on its predecessor)”. He describes the first movement as “mercurially restless” and though there’s still a tendency to discursiveness it seems to me that Magnard is now writing with greater assurance – and he certainly handles the orchestra with increased discernment and confidence. I find Ossonce brings a bit more life to the music of I - Sanderling’s tempo is steadier though it’s convincing in isolation. The third movement is a rich, warm creation, which rises to an opulent, ardent climax. Ossonce is very convincing. This is one of the movements where the differences between him and Sanderling are most marked. Sanderling takes 15:11, compared with Ossonce’s 12:11. That’s quite a difference. Sanderling invests the music with an almost Brucknerian breadth, especially at the start. Ossonce certainly doesn’t short change the listener but his reading has more forward movement, I feel. The finale lives up to its marking, ‘Vif et gai’, in Ossonce’s often bustling and sparkling reading and he ensures that the symphony ends in a mood of joyous affirmation.

The Third was recorded a good many years ago by Ernest Ansermet and his version has recently been reissued (see review). I’d agree with Ian Lace’s assessment that the symphony is “very approachable and has memorable, melodious material.” In fact, while the Fourth may outrank it in terms of ambition, there are good grounds for regarding the Third as the best of the canon. The solemn, mysterious opening to I is very ear-catching and it’s very well rendered by Ossonce and his team. Sanderling shapes the introduction very atmospherically but I wonder if he draws it out too much – he takes 3:19 over the passage while Ossonce requires 2:08. The main allegro arrives abruptly – Sanderling just a fraction steadier than Ossonce – and as Pott puts it “there is a consistent sense that the more unbridled passions of the second symphony are here under the iron control of formal academicism”. By this I’m sure he doesn’t mean that the music is academic – it certainly is not – but that it has more rigour and discipline than one has encountered previously. There’s plenty of vitality in this movement and the prevailing character is positive. There’s a lovely, pensive second subject, which exhibits Magnard’s lyric gifts. All in all this is a fine movement. The scherzo is exhilaratingly nimble with the playing being quite delightful and with a gentler, more reflective central episode. The third movement opens with a ruminative cor anglais solo but the strings are generally to the fore in this rather intense movement. The BBC Scottish players acquit themselves extremely well once again. This is another movement where there is a substantial difference between the two rival versions. Where Ossonce takes 8:21 Sanderling draws the music out to 11:44. The opening cor anglais theme is a case in point. It’s lovely and highly expressive in the Sanderling version but one senses that the more flowing tempo adopted by Ossonce may be the better course, though I need to get to grips more with Sanderling’s version to be sure. The finale has much good humour and the music is often bustling though, characteristically, Magnard can’t resist lyrical dalliances along the way. Ossonce leads a performance full of life and character.

To judge from his comments Francis Pott sees the Fourth as Magnard’s most important symphony. It’s certainly his most ambitious. Pott describes it as being on a “formidably expansive scale - Mahlerian in breadth if not in actual length.” The first movement, in which Magnard seems to me to reach out to new horizons, begins most unusually with an upward swirling figure on the woodwind choir. To quote Pott once more: “This is turbulent music of a splendid orchestral virtuosity.” As so often in the earlier symphonies, the playing of the BBC Scottish orchestra is first class; it’s ardent and sonorous but also agile when required. This is the biggest music we’ve yet encountered in the cycle and it also seems to me to be some of the tightest. The brief scherzo is lighter on its feet but even here the music still has purpose. The extended slow movement is a soulful utterance, rising to a passionate climax where the orchestration is particularly richly hued, before quite quickly subsiding to a peaceful close. I admire the way in which Ossonce and the orchestra maintain the tension throughout this movement. To round off the symphony there’s a finale, which is often urgent and animated. At its heart there’s a massive chorale-like climax. In his notes Francis Pott draws several points of comparison with Mahler. I have to say that I don’t really get the connection yet, though I may well do so with repeated listening. However, at this juncture I do feel a kinship with Mahler’s Fifth. The work ends with a surprisingly brief, pacific coda.

In the early months of World War I Albéric Magnard met a tragic and untimely end at the hands of German soldiers. Who knows what he might have achieved had he lived longer? On the evidence of these performances I’d hesitate to call him a major symphonist but his four symphonies are far from inconsiderable achievements and show him to have been evolving his symphonic language and his use of the orchestra very impressively. He certainly had something original to say and his symphonies are well worth hearing. Sadly, it’s unlikely that they’ll ever achieve much more than the most tenuous of toeholds in the symphonic repertoire, even in his native France. That’s the value of recordings.

Jean-Yves Ossonce and the BBC Scottish prove to be committed, persuasive and skilful advocates for these works. Particular credit must go to the orchestra for these works will have been unfamiliar to them. They sound to include many technical difficulties yet the orchestral playing is first class throughout. I should repeat that such comparisons as I’ve been able to make with the Sanderling set have been limited and I wouldn’t have the temerity to express a preference at this stage. However, the two conductors seem to have quite differing views of the music at times and it’s great to have the opportunity to hear this unfamiliar repertoire in contrasting versions. From what I’ve heard of them Sanderling’s performances are well recorded and very well played and I look forward to appreciating them properly in due course.

For now, however, these Ossonce performances will do very nicely indeed as an introduction to this neglected composer and his symphonies. The performances are consistently excellent and persuasive. Hyperion have provided rich, detailed recorded sound and Francis Pott’s notes are out of the top drawer. Now reissued at a most attractive price, this set is a compelling proposition. ---John Quinn, musicweb-international.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex mediafire uloz.to cloud.mail.ru