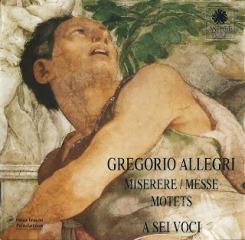

Allegri – Miserere, Messe, Motets (A Sei Voci) [1994]

Allegri – Miserere, Messe, Motets (A Sei Voci) [1994]

1 Misere (à Neuf Voix, Version avec Ornements Baroques) 14:25 Messe Vidi Turbam Magnam (Messe à Six Voix) 2 Introït : Statuit Ei Dominum (Plain-chant) 2:49 3 Kyrie 2:40 4 Gloria 3:20 5 Graduel : Exaltent Eum (Plain-chant) 3:04 6 Credo 6:33 7 Sanctus 3:20 8 Agnus Dei 3:10 Motets 9 De Ore Prudentis (Motet à Trois Voix et Continuo) 1:52 10 Repleti Sunt Omnes (Motet à Trois Voix et Continuo) 1:39 11 Cantate Domino (Motet à Quatre Voix et Continuo) 3:02 12 Miserere (à Neuf Voix) 15:12 Dominique Ferran – Organ A Sei Voci - Vocal Ensemble Bernard Fabre-Garrus - Director

This 1994 disc is something of a classic of the new strain of the historical-performance movement, which is characterized by a certain amount of license to speculate in the reconstruction of lost works. The Miserere mei Deus of Gregorio Allegri is, of course, not a lost work, but one with an unbroken performance tradition stretching back to its composition in the early seventeenth century (before 1638). It was sung for centuries at the Sistine Chapel, where the singers were enjoined from circulating the music beyond Vatican walls. That prohibition wasn't enough to stop the 12-year-old Mozart, who wrote most of it down by ear as a tourist in Rome and filled in the gaps on a quick return visit; soon after that, British music writer Charles Burney got hold of either Mozart's copy (which hasn't survived) or another one and published the work. But by that time the Miserere had itself changed from what Allegri might have imagined. The work, which stood in a tradition of similar, earlier pieces, had an improvisational component, drawing on a centuries-old process of elaboration and harmony singing known as falsobordone (fauxbourdon in French, faburden in English). The Vatican singers, as the booklet explains and illustrates with contemporary quotations, gradually lost the skill to execute these improvisations, and the work took on the vivid but fixed contrasts between two choirs that are known today. French conductor Bernard Fabre-Garrus and his small choir A Sei Voci try, in the first track on the album, to reconstruct the work as Allegri might have heard it. The singers add a mostly upper line of counterpoint and elaborate it floridly, creating music that's completely different in effect, more spectacular and extroverted, than the Miserere. Fabre-Garrus exaggerates the contrast by calling for a sharp, coruscating sound from the singers and the initial Miserere, but then reining them in for the later version, performed at the end of the disc. The pairing offers a crash course in how much our understanding of seventeenth century music has been shaped by performance traditions. In between comes other music by Allegri, almost completely unknown but highly listenable and relevant in various ways to the mystery of the Miserere. The Missa vidi turbam magnam is a good example of what happened when composers tried to adapt the intrinsically conservative form of the mass to the new musical language of the seventeenth century; it is outwardly a work in the polyphonic stile antico of the Renaissance, but it is full of sunny major harmonies and direct harmonic moves that show the influence of modern styles. The three motets that follow (tracks 9-11) are in the new, continuo-accompanied manner; they are for three or four solo voices, in lush, close harmonies, and are accompanied here by a small organ. Altogether this was a disc that did much to illuminate a work whose connection to the extreme tendencies of the seventeenth century had mostly been forgotten, and it has inspired tribute in the form of various further attempts to refine performance of the Miserere mei Deus. ---James Manheim, Rovi

Gregorio Allegri (1582-1652) surpassed himself in the composition of the "Miserere". He was a very fine composer, the successor to Palestrina and Nanino among the corps of singer/composers who made up the Pope's own chapel choir. His "Missa Vidi Turbam Magnam" - performed superbly on this CD - is a candidate in my estimation for the best post-Counterreformation liturgically acceptable mass, during the several centuries when the Catholic musical world was bifurcated between the "excesses" of the Baroque and the frozen purity of the Palestrina legacy. In other words, Allegri was the consummate musical conservative, writing 16th C polyphony for performance in the secret depths of the 17th C Vatican.

But as I said, the "Miserere" earned a distinction beyond anything else Allegri wrote. It was the private, closely guarded masterpiece of the Papal choir, performed only once a year, every year, during Holy Week in the Sistine Chapel. The very finest singers - including the castrati of the Vatican - sang the "Miserere" at the end of the Tenebrae service; while the Pope and cardinals knelt, the candles in the chapel were extinguished one by one. The singers were expected to improvise embellishments in the precise tradition of the Renaissance. By the end of the 18th C, when the child Mozart was one of the invited guests present at the Tenebrae, the skills of the Papal Choir were no longer sufficient for such improvisation, and a standard version of the Miserere was committed to paper, with embellishments concentrated in the soprano line, memorized by the castrati. That's the version of the Miserere which has been performed ever since, and recorded by various choirs in our times.

A Sei Voce performs the Miserere twice on this CD. The final track represents the late 17th C written version. The first track represents an effort to recreate the Miserere as it might have been sung in Allegri's own lifetime, with complex cadential ornamentation in all voices, not improvised but based on the research of Jean Lionner, a musicologist. Both versions are sung exquisitely, with women's voices taking the castrati roles. I imagine that some listeners will prefer the chaste simplicity of the later version. Myself, I find the ornamented reconstruction very interesting but perhaps a bit forced and formalized. I wonder whether the singers of A Sei Voci mightn't have done better to trust their own extempore skills at embellishment, in order to sound freely natural.

Those singers of A Sei Voci, by the way, can sing up a storm! They are good! A mixed chorus of women and men, they nonetheless produce a balanced and blended timbre, a spectrum of voices without an obvious break in color between the higher and lower voices. On the basis of this performance, I'd rank them with The Clerks' Group and the Binchois Consort at the apex of ensemble singing today. Bernard Fabre-Garrus, the director of the ensemble, deserves special accolades for his orotund yet flexible bass voice. ---Gio, amazon.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega mediafire cloudmailru uplea