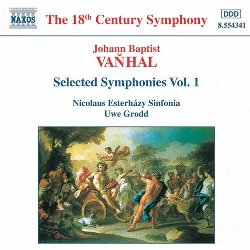

Johann Baptist Vanhal - Selected Symphonies Vol.1 (1999)

Johann Baptist Vanhal - Selected Symphonies Vol.1 (1999)

Sinfonia in A major, Bryan A9 1. I. Allegro moderato - 4:34 2. II. Andante molto - 3:58 3. III. Tempo di primo - 4:31 Sinfonia in C major, Bryan C3 4. I. Allegro con spirito - 5:09 5. II. Andante - 3:01 6. III. Presto - 2:37 play Sinfonia in D major, Bryan D17 7. I. Andante molto - Allegro moderato - 7:45 8. II. Adagio molto - 4:31 play 9. III. Finale: Allegro - 5:54 Symphony in C major, Bryan C11, "Il comista" 10. I. Allegro con brio - 4:14 11. II. Andante cantabile - 6:44 12. III. Finale: Adagio piu andante - Allegro - 3:04 Budapest Nicolaus Esterhazy Sinfonia Uwe Grodd - conductor

Johann Baptist Vaňhal was one of the most popular Viennese composers during his lifetime. History has, however, been unkind to his reputation, the result of irresponsible statements that were made by imaginative authors who were not acquainted with him or his circumstances. The general impression is that he was melancholy and depressed when, in truth, he appears to have been basically happy and personable. Wild claims have also been made that early in his career he was so overcome by madness caused by religious fervour that he burned some of his music. After that, the story goes, the quality of compositions deteriorated so much that he never realised the promise of his early works. The lie to this assertion is given by the splendid symphonies included on this CD. It contains the Sinfonia in C major, C3, one of his earliest works, along with three of his later ones, including the Sinfonia in D major, D17, which I believe to be one of his last. His vitality and inventiveness are evident in all of them.

One part of Vaňhal's reputation is, however, true. He was the first major composer of the time who was strong enough to renounce the offer of a 'good' - and terribly demanding position - and to live comfortably until he died in Vienna at the age of seventy-four. His success was possible because of his other personal characteristics. He was humble and deeply religious - not ambitious for fame, high position, or fortune. He was also shrewd, hard-working and sensitive to changing economic and social conditions. As a result he decided to cease composing symphonies and chamber music when the market in Vienna was drying up in about 1780, and began to explore other possibilities.

The results were spectacular. He composed, for example, more than 247 works (mostly unpublished), large and small, for the church. He also wrote a huge number of pieces all of which centred around the keyboard. His compositions included serious works, such as the keyboard Capriccios, and songs and cantatas for voice with keyboard accompaniment. He also published many pieces for instruction and entertainment which became very popular, including imaginative pieces with descriptive titles such as The Battle of Trafalgar. In all he produced more than 1300 compositions in a wide variety of genres. To the present, only the symphonies and string quartets have been sufficiently studied to ascertain his complete contribution.

The four symphonies included here provide a good introduction to Vaňhal's symphonic style and illustrate why he was considered such an important exponent of the genre. The Sinfonia in A major, A9, was probably composed ca 1775-78, at about the same time as the Sinfonia in C major, C11. That it was written by Vaňhal is not confirmed by any of the usual eighteenth-century catalogues or references; however, there are no contra-attributions. Its claim for legitimacy is confirmed by its stylistic factors, especially by similarities with other accepted works of the same period. The clearly established authenticity of the Sinfonia, C11, which in some respects it resembles, therefore serves as a touchstone for the A major work, especially in view of Vaňhal's long-demonstrated creativity, innovative ability and interest in experimenting with approaches to composing symphonies.

The most striking feature of the Sinfonia is its overall construction as a multi-tempo one-movement symphony. The outer movements, brilliantly scored with oboes and clarini (in D), enclose a captivating central 'movement' in which Vaňhal makes magical use of a solo cello doubled at the upper octave by the first violins. This exuberant and powerful symphony has one further surprise to spring: the Finale concludes with a hushed quotation of the opening measures of the symphony thus emphasizing its unique structure in the most dramatic way possible.

I believe that the Sinfonia in C major, C3 was one of the earliest of Vaňhal's symphonies and that it was probably composed in 1760-62. The "No.1" inscribed on the title-page of the copy from the Doksy collection, now preserved in the Narodni Museum in Prague, helps to confirm that it is one of Vaňhal's earliest symphonies and that he might even have written it before he came to Vienna. The Sinfonia is in three-movement Overture style with segue indicated between the movements in several versions. The basic instrumentation probably called for strings with a wind choir of two oboes, two horns, two trumpets (clarini) and timpani.

However, some versions call only for clarini and others for horns only; some call for both and omit the timpani, as is the case in this recording. Regardless, it is a brilliant and exciting symphony which must have caught the attention of soiree audiences during Vaňhal's first years in Vienna. The Finale (Presto) opens with a 'stomping' rhythm which permeates the entire movement; one wonders if the movement was ever danced to. The Sinfonia in D major, D17 is one of three symphonies published in 1780 as Op.10 by J.J. Hummel in Berlin. They were the last of Vaňhal's symphonies to be newly published and I estimate that they were composed ca 1779.

All the evidence suggests that these symphonies were commissioned by Hummel and that the extant manuscript sets of parts in various archives were copied direct from Op.10 rather than from an earlier source. The Sinfonia is a fine work; I believe that it is one of Vaňhal's best. From the haunting D minor introduction scored for strings (with muted violins) to the dashing and brilliantly composed finale, the work is uniformly strong and quite the equal of any of Haydn's symphonies of the period. At first glance it appears to be in three movements, but the Andante molto opening has a life of its own - much the same as the Adagio openings to Mozart's 'Linz' Symphony No.

36 in C major, K. 425, composed in 1783 and to Symphony No. 38 in D, K. 504, composed in 1786. Mozart's prominent use of the chromatic rising figure in the introductions to both symphonies is similar to that found in bars 33-35 of Vaňhal's introductory movement. Further, his use of Vaňhal's opening motif from the introductory movement as the basic ingredient for the Poco Adagio second movement of K. 425 suggests that Mozart may have been impressed with Vaňhal's Sinfonia at some point before he composed K. 425. Certainly the critic C.F. Cramer was impressed. Writing in the Magazin der Musik in Hamburg in 1783 he said: "may Herr Vaňhal not be prevented ... from giving us more such symphonies".

One of Vaňhal's late symphonies, the Sinfonia in C major, C11, was most likely composed during the period 1775-78. One contemporary copy of the work is styled Sinfonia comista / con per la sorte diversa on the title-page. The headings for the individual movements are marked, I. Sinfonia la Speranza / Allegro con Brio, II. Andante cantabile / il sospirare e Languire, and III. at the beginning: Finale: la Lamentazione / Adagio piu Andante and after 17 bars L'Allegrezza / Allegro. The symphony is, therefore, a programmatic work, whose individual movements are supposed to portray varied moods: I. 'Hope', II. 'Sighingly and Languidly' and III.

'Lamentation', followed by 'Gaiety, Cheerfully and Festive'. It must have been composed for an imaginative patron who would have appreciated being informed by the titles and intent of each movement. The upbeat mood (hope) established by the busy and active opening movement in C major sets up expectations that the happy tone will continue. The expectation is, however, dashed by the lengthy slow movement in C minor and the dark mood created by its scoring with parts for divided violas, horns in E-flat and, in some sources, two bassoons. The solo introduction (also in C minor) to the Finale movement would also have surprised contemporary listeners and the musically astute among them would have been pleased to recognise that the Adagio introduction contains a figure that foreshadows both of the main motifs from which the following Allegro is constructed. The final outcome caused by the triumphant C major finale must surely have delighted audiences of the time. ---Paul Bryan, naxosdirect.com

download: uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire solidfiles mega zalivalka filecloudio anonfiles oboom

Last Updated (Thursday, 12 June 2014 09:02)