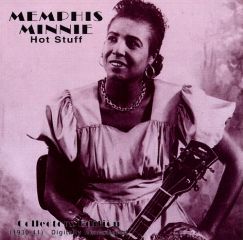

Memphis Minnie - Hot Stuff 1930-1941 (1996)

Memphis Minnie - Hot Stuff 1930-1941 (1996)

1 Hot Stuff, 3:02 2 I Hate to See the Sun Go Down, 2:43 3 Memphis Minnie-Jitis Blues, 3:20 4 Frankie Jean (That Trottin' Fool), 2:49 5 She Put Me Outdoors, 2:47 6 I Don't Want That Junk Outta You, 2:22 7 Biting Bug Blues, 3:19 8 Moonshine, 2:46 9 Chickasaw Train Blues (Low Down Dirty Thing), 3:14 10 Down by the Riverside, 2:31 11 I Called You This Morning, 2:58 12 Man, You Won't Give Me No Money, 2:56 13 Keep on Sailing, 3:01 14 It's Hard to Be Mistreated, 3:05 15 New Bumble Bee, 2:50 16 Me and My Chauffeur Blues, 2:44 17 Good Morning, 2:57 18 Ice Man (Come on Up), 2:58 Memphis Minnie - Banjo, Composer, Guitar, Vocals Blind John Davis - Piano Little Son Joe – Guitar Ransom Knowling – Bass Fred Williams – Drums + Unknown Artists

Memphis Minnie began performing with Joe McCoy, her second husband, in 1929. They were discovered by a talent scout for Columbia Records, in front of a barber shop, where they were playing for dimes. She and McCoy went to record in New York City and were given the names Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie by a Columbia A&R man. Over the next few years she and McCoy released a series of records, performing as a duet. In February 1930 they recorded the song "Bumble Bee" for the Vocalion label, which they had already recorded for Columbia but which had not yet been released. It became one of Minnie's most popular songs; she eventually recorded five versions of it. Minnie and McCoy continued to record for Vocalion until August 1934, when they recorded a few sessions for Decca Records. Their last session together was for Decca, in September. They divorced in 1935.

An anecdote from Big Bill Broonzy's autobiography, Big Bill Blues, recounts a cutting contest between Minnie and Broonzy in a Chicago nightclub on June 26, 1933, for the prize of a bottle of whiskey and a bottle of gin. Each singer was to sing two songs; after Broonzy sang "Just a Dream" and "Make My Getaway," Minnie won the prize with "Me and My Chauffeur Blues" and "Looking the World Over". Paul and Beth Garon, in their biography Woman with Guitar: Memphis Minnie's Blues, suggested that Broonzy's account may have combined various contests at different dates, as these songs of Minnie's date from the 1940s rather than the 1930s.

By 1935 Minnie was established in Chicago and had become one of a group of musicians who worked regularly for the record producer and talent scout Lester Melrose. Back on her own after her divorce from McCoy, Minnie began to experiment with different styles and sounds. She recorded four sides for Bluebird Records in July 1935, returned to the Vocalion label in August, and then recorded another session for Bluebird in October, this time accompanied by Casey Bill Weldon. By the end of the 1930s, in addition to her output for Vocalion, she had recorded nearly 20 sides for Decca and eight sides for Bluebird. She also toured extensively in the 1930s, mainly in the South.

In 1938 Minnie returned to recording for the Vocalion label, this time accompanied by Charlie McCoy, Kansas Joe's brother, on mandolin. Around this time she married the guitarist and singer Ernest Lawlars, known as Little Son Joe. They began recording together in 1939, with Son adding a more rhythmic backing to Minnie's guitar. They recorded for Okeh Records in the 1940s and continued to record together through the decade. By 1941 Minnie had started playing electric guitar, and in May of that year she recorded her biggest hit, "Me and My Chauffeur Blues". A follow-up date produced two more blues standards, "Looking the World Over" and Lawlars's "Black Rat Swing" (issued under the name "Mr. Memphis Minnie"). In the 1940s Minnie and Lawlars continued to work at their "home club," Chicago's popular 708 Club, where they were often joined by Broonzy, Sunnyland Slim, or Snooky Pryor, and also played at many of the other better-known Chicago nightclubs. During the 1940s Minnie and Lawlars performed together and separately in the Chicago and Indiana areas. Minnie often played at "Blue Monday" parties at Ruby Lee Gatewood's, on Lake Street. The poet Langston Hughes, who saw her perform at the 230 Club on New Year's Eve, 1942, wrote of her "hard and strong voice" being made harder and stronger by amplification and described the sound of her electric guitar as "a musical version of electric welders plus a rolling mill." ---revolvy.com

download (mp3 @64 kbs):