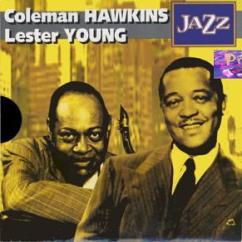

Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young (2000)

Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young (2000)

01 - Coleman Hawkins - Hello Lola - 1929 02 - Coleman Hawkins - One hour - 1929 03 - Coleman Hawkins - Jamaica shout - 1933 04 - Coleman Hawkins - Star dust - 1935 05 - Coleman Hawkins - Out of nowhere - 1937 06 - Coleman Hawkins - She's funny that way - 1939 07 - Coleman Hawkins - Body And Soul [1939] 08 - Coleman Hawkins - My ideal - 1943 09 - Coleman Hawkins - The man i love - 1943 10 - Coleman Hawkins - Yesterdays - 1944 11 - Coleman Hawkins - Rainbow mist - 1944 12 - Lester Young - Them there eyes - 1938 13 - Lester Young - Lester leaps in - 1939 14 - Lester Young - Just you, just me - 1943 15 - Lester Young - Afternoon of a Basie-ite - 1943 16 - Lester Young - Sometimes i'm happy - 1943 17 - Lester Young - I can't get started - 1942 18 - Lester Young - Blue Lester - 1944 19 - Lester Young - Ghost of a chance - 1944 20 - Lester Young - D.B. blues - 1945 21 - Lester Young - Lester blows again - 1945 22 - Lester Young - These foolish things - 1945 23 - Lester Young - I cover the waterfront - 1946

By the end of the swing era, Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young exemplified the two main approaches to playing tenor sax. Throughout his career, the soft-spoken and distinguished Coleman Hawkins always took pride in his ability to be modern and open to newer ideas. He had emerged in 1921 with Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds and joined Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra in 1923 as the first tenor saxophone jazz soloist, but although technically skilled, his style was rhythmically awkward. After playing next to Louis Armstrong on a nightly basis, he smoothed out his style, discarded his reliance on effects, and learned to create meaningful improvisations. A master at chordal improvising, Hawkins was never bothered by later developments; he was usually ahead of the game. While with Henderson from 1923 to 1934, he easily dominated other tenor players with his large, thick tone. Frustrated by the Henderson band’s lack of progress compared to that of Duke Ellington, he left the orchestra after eleven years to spend five years in Europe, playing with local orchestras on the Continent and in England.

With Hawkins gone, other tenor players, most notably Lester Young, Ben Webster, and Chu Berry, emerged as rivals. When he returned in 1939 and played in jam sessions, Hawkins showed that he was still the king of tenors, and that he had not stood still while overseas. That year, apparently as a last minute throwaway at a record date, he recorded a famous version of “Body and Soul” that has two choruses in which he barely hints at the melody, creating new ideas of his own.

In 1940 Hawkins led a big band, but it never caught on and soon broke up. Instead, he led a series of combos that often performed at Fifty-second Street. Between 1943 and 1946 he recorded one gem after another, including a classic version of “The Man I Love” and sets in which he welcomed such younger bebop musicians as drummer Max Roach, trombonist J. J. Johnson, trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro, and Miles Davis, and pianist Thelonious Monk, who made his recording debut with Hawkins. Although most tenors now had a lighter sound than Hawkins, harmonically he was keeping up with the next generation. With his rhythms considered old-fashioned, he was a bit overlooked during the first half of the 1950s but was an early influence on the young tenor Sonny Rollins. By 1957 his longevity and consistent greatness was being recognized, and Hawkins recorded everything from Dixieland and swing to bop, and a date led by his former pianist Monk that found him holding his own alongside John Coltrane. Hawkins continued to be a major force until 1966 when bad health caused his rapid decline and death three years later.

Lester Young was always an individualist, a quiet revolutionary who blazed his own musical path. As a child he played trumpet, violin, drums, and alto with his father in the Young Family Band. Lester settled on alto but switched to tenor when he worked with Art Bronson’s Bostonians in 1928 and 1929. After playing with the Original Blue Devils in 1932and 1933, Count Basie in 1934, Bennie Moten, and King Oliver, he got his big break as Coleman Hawkins’ replacement with Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra. His radical style was too different to suit the Henderson sidemen, and he was reluctantly let go after three months. Young sounded like he was playing a new instrument altogether. His tone was very light, he floated over bar lines, and he always sounded relaxed, even when the tempos were fast. He was the epitome of “cool.”

After Young rejoined the Count Basie band in 1936, he was a major part of their success during the next four years, traveling to New York and being its top soloist. On the very first record date in late 1936, Young emerged fully formed, taking a perfect solo on “Lady Be Good.” He recorded frequently with Basie, and starting in 1937 often with Billie Holiday, a close friend. He named her “Lady Day” and she called him “Pres.”

For some reason, maybe because he did not want to record on Friday the thirteenth, Lester Young left the Basie band in December 1940. The next two years were largely uneventful; he made relatively few recordings, and his own band did not catch on. In October 1943 he rejoined Basie, and although the recording strike kept the full orchestra off records, Young made some classic small-group records and appeared in the Academy Award-winning short film Jammin’ the Blues .

In the summer of 1944, Young was drafted. The military was the wrong place for the introverted and sensitive saxophonist, and he experienced a horrible year, including time in a military prison. Young was unsuited for military life and the institutional racism of the period. The experience left him emotionally scarred and depressed. After his discharge, Young at first played at his peak. He led combos during the next decade, toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic, and was well paid. He was greatly respected by the younger musicians; many copied his sound and approach. But his drinking increased and his state of mind gradually deteriorated during the 1950s. By then he had invented a language of his own, full of eccentric slang that was only understood by his closest friends, shielding himself as best he could from the world. Although he rallied on several occasions and often played quite well, Lester Young eventually drank himself to death, passing away in 1959 at the age of forty-nine. ---encyclopedia.jrank.org

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

uploaded yandex 4shared mega solidfiles cloudmailru filecloudio oboom

Last Updated (Friday, 16 January 2015 20:30)