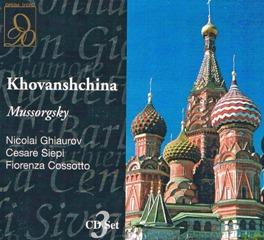

Mussorgsky - Khovanshchina (1973)

Mussorgsky - Khovanshchina (1973)

1. CD1 - Prologue - Act I - Act II 2. CD2 - Act II (Cont’d) - Act III 3. CD3 - Act IV - Act V Ivan Khovansky - Nicolai Ghiaurov Andrey Khovansky - Veriano Luchetti Vasily Golitsyn - Ludovic Spiess Shaklovity - Siegmund Nimsgern Dosifey - Cesare Siepi Marfa - Fiorenza Cossotto Susanna - Elena Souliotis Scribe - Franz Handlos Emma - Mietta Sighele Kuzka - Angelo Marchiandi Streshniev - Claudio Strudthoff Pastor - Giovanni Sciarpeletti Varsonofiev - Ubaldo Carosi Strelets I - Teodoro Rovetta Strelets II - Carlo Del Bosco RAI Roma Orchestra and Chorus Bogo Leskovich – conductor

Khovanshchina (The Khovansky Affair) was Modest Mussorgsky's final opera, left unfinished at the time of this death in March of 1881. Inconsistencies among the variety of completed editions makes pinning down its essential nature difficult. Ironically, this dramatic and musical malleability is perhaps what best suits Khovanshchina to its subject matter, namely the ascension of Tsar Peter I ("The Great"). Depending on one's perspective, the changes he wrought were either the most beneficial or most tragic in Russia's history, and, depending on which version of Khovanshchina one encounters in performance, one either leaves with a sense of emerging optimism or a sense of desperate resignation.

Khovanshchina takes its name from the two Khovansky princes, Ivan and Andrey, whose Strel'tsï musketeers rose up against the new Tsar in 1689. However, the adoption of their family name for the work's title is potentially misleading; while the drama is related through the eyes of the three principle groups that opposed Peter's reign (the Khovanskys, the schismatics ["Old Believers"], and the family of Peter's older brother), the Tsar himself and his historical legacy are clearly the focus of the opera. Had censorship not explicitly proscribed the depiction of Russian royalty on stage, Khovanshchina would have taken a very different shape, and most likely a different name.

Vladimir Vasil'yevich Stasov compiled the libretto from various historical documents, and the resulting text remains truthful, in the broad sense, to history. However, there is no attempt to recreate the specific events therein; rather, the various figures and events are used as raw material for the invention of appropriately operatic scenes. The most conspicuous liberty was the character of Marfa, who is a member of the schismatic sect, the lover of Andrey Khovansky, and a fortune teller with influence over Ivan's chief agent, Prince Golitsïn. Completely a work of fiction, she is the only character in the opera who has ties to all three factions, and as such she takes on a unique dramatic importance. Stasov most likely invented her to compensate for his inability to depict the Tsar himself -- the work's only true common thread -- on stage.

Mussorgsky conceived of Khovanshchina in six scenes, the last two of which only survive as sketches; they form matched pairs, so that each of the three opposition factions receives two -- one in which they are seen plotting against Peter, and one in which they meet their demise. For its 1886 premiere, Rimsky-Korsakov completed and orchestrated the work, and cast it into the five-act form that has become standard; this edition was subsequently used for its 1911 revival and Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky's own 1913 revision. In his completion, Rimsky-Korsakov recycled some of the more uplifting passages from the orchestral prelude for use in the final scene, in which the "Old Believers" -- those who advocated the return to a church-based government -- leave to commit ritual suicide in protest of Peter's ascension. By doing this, Rimsky-Korsakov gave the ending a philosophical "shot in the arm" by suggesting that, despite the upheaval that accompanied Peter's reign, the resulting "modern era" of Russian society was worth the price. There is evidence from Mussorgsky's correspondence that he never intended this, but rather wanted the disenfranchised believers' sacrifice to speak to a greater sense of national loss. In 1952, Dmitri Shostakovich fashioned an entirely new version of the score for use in a film version. This new score was published in 1963, and has been used for a number of modern performances; it is arguably more representative of Mussorgsky's dramatic intentions. ---Allen Schrott, Rovi

download: uploaded yandex 4shared mediafire solidfiles mega filecloudio nornar

Last Updated (Saturday, 01 March 2014 16:02)