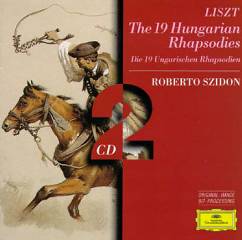

Franz Liszt - The 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies (1996)

Franz Liszt - The 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies (1996)

1-01 Rhapsody No. 1 14:16 1-02 Rhapsody No. 2 9:14 1-03 Rhapsody No. 3 4:17 1-04 Rhapsody No. 4 4:40 1-05 Rhapsody No. 5 10:18 1-06 Rhapsody No. 6 6:27 1-07 Rhapsody No. 7 5:40 1-08 Rhapsody No. 8 5:59 1-09 Rhapsody No. 9 10:46 1-10 Rhapsody No. 10 5:23 2-01 Rhapsody No. 11 5:38 2-02 Rhapsody No. 12 9:40 2-03 Rhapsody No. 13 9:06 2-04 Rhapsody No. 14 11:49 2-05 Rhapsody No. 15 6:01 2-06 Rhapsody No. 16 5:25 2-07 Rhapsody No. 17 3:21 2-08 Rhapsody No. 18 3:03 2-09 Rhapsody No. 19 11:47 2-10 Rhapsody Espagnole 13:20 Roberto Szidon – piano

According to Charles Rosen, the Hungarian Rhapsodies represent "the least respectable side of Liszt." Their charm lies not in their musical invention, but in their dazzling expansion of the range of expression possible on the piano, or, as Rosen puts it, "the various noises that can be made with a piano."

When Liszt visited Hungary in 1839, he had been away from the country for 13 years. This visit, plus another in 1840, prompted the production of ten volumes of piano pieces between 1840 and 1847 based on Hungarian themes. In 1851-1853, Liszt published 15 of these works as the Hungarian Rhapsodies, composing and publishing four more in 1882-1886.

While in Hungary, Liszt transcribed numerous melodies performed by indigenous gypsy bands. By using these "ancient" melodies in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, Liszt saw himself as immortalizing the Hungarian race. Actually, many of the tunes Liszt rhapsodized were written by contemporary Hungarian composers and had become popular outside the cities. Like most tourists, Liszt didn't care. He also didn't care that the blatantly flashy, non-musical piano passages in all of the Rhapsodies prompted the contempt of Schumann and Chopin.

The large-scale organization of Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsodies derives from the multi-sectional nineteenth century verbunkos. The Verbunkos is a Hungarian dance style derived from the method of recruiting troops in Hungary in the eighteenth century. It features at least two contrasting sections: the slow lassu, or lassan, and the fast friss, or friska. Liszt varies the number and order of these in the various Rhapsodies, in some cases linking the sections, in others, creating a stream of unrelated ideas in the traditional fashion of a rhapsody.

In the second of Liszt's Rhapsodies, we hear one lassu followed by one lengthy friss, all prefaced by a brief introduction. Typically, the sudden changes of material interrupt what would otherwise be a constant race to the end. While the lassu maintains the opening key of C sharp minor until its very close, the friss is generally in the major mode, closing on F sharp major.

Liszt's approach to the lassu/friss structure is somewhat different in Rhapsody No. 13, in A minor. In the opening lassu, he puts two motives from the second melody through developmental treatment. This leads to a climax, a concept far removed from the gypsy style of music performance. Liszt makes conspicuous use of one Hungarian scale, with a raised fourth degree, while other Hungarian scales appear in Nos. 16 and 17, both beginning in minor keys.

Western art music also permeates Rhapsody No. 14, in F minor. The piece begins with a somber melody with a distinctive rhythmic pattern. In the friss, the same tune and rhythm appear in thick chords, smoothing over the sudden changes that are typical of the traditional verbunkos.

The eleventh Rhapsody adheres more closely to the "gypsy style." Opening with a lento a capriccio, the piece gradually accelerates through three sections, the first of which is a typical verbunkos, the next two evoking the style of the Hungarian csárdás. ---John Palmer, Rovi

download: uploaded yandex anonfiles 4shared solidfiles mediafire mega filecloudio nornar

Last Updated (Friday, 31 January 2014 20:26)