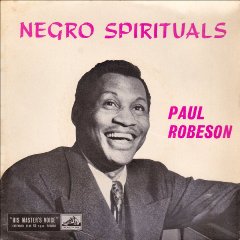

Paul Robeson – Negro Spirituals (1982)

Paul Robeson – Negro Spirituals (1982)

A1 Hammer Song 2:05 A2 Water Me From The Lime Rock 1:35 A3 Scandalize My Name 1:55 A4 Jacob´s Ladder 2:55 A5 Wittness 2:10 A6 Stand Still, Jordan 3:20 A7 Takin´ Names 2:25 A8 Swing Low, Sweet Chariot 2:08 B1 No More Auction 2:10 B2 Some Day He´ll Make It Plain To Me 3:30 B3 Didn´t Me Lord Deliver Daniel 1:20 B4 Bear The Burden In The Heat Of Day 3:14 B5 Mount Zion: "On My Journey" 2:19 B6 I´m Gonna Let It Shine 2:27 B7 Let Us Break Together On Knees 1:55 B8 Amazing Grace 3:30 Paul Robeson – vocals Alan Booth – piano Brownie McGhee – guitar (A1) Sonny Terry – harmonica (A1) Lawrence Brown – vocals, piano (A5)

The tunes and the beats of negro spirituals and Gospel songs are highly influenced by the music of their actual cultural environment. It means that their styles are continuously changing.

The very first negro spirituals were inspired by African music even if the tunes were not far from those of hymns. Some of them, which were called "shouts" were accompanied with typical dancing including hand clapping and foot tapping. Some African American religious singing at this time was referred as a "moan" (or a "groan"). Moaning (or groaning) does not imply pain. It is a kind of blissful rendition of a song, often mixed with humming and spontaneous melodic variation. In the early nineteenth century, African Americans were involved in the "Second Awakening". They met in camp meetings and sang without any hymnbook. Spontaneous songs were composed on the spot. They were called "spiritual songs and the term "sperichil" (spiritual) appeared for the first time in the book "Slave Songs of The United States" (by Allen, Ware, Garrison, 1867).

As negro spirituals are Christian songs, most of them concern what the Bible says and how to live with the Spirit of God. For example, the "dark days of bondage" were enlightened by the hope and faith that God will not leave slaves alone.

By the way, African Americans used to sing outside of churches. During slavery and afterwards, slaves and workers who were working at fields or elsewhere outdoors, were allowed to sing "work songs". This was the case, when they had to coordinate their efforts for hauling a fallen tree or any heavy load. Even prisoners used to sing "chain gang" songs when they worked on the road or on some construction project.

But some "drivers" also allowed slaves to sing "quiet" songs, if they were not apparently against slaveholders. Such songs could be sung either by only one soloist or by several slaves. They were used for expressing personal feeling and for cheering one another. So, even at work, slaves could sing "secret messages". This was the case of negro spirituals, which were sung at church, in meetings, at work and at home.

The meaning of these songs was most often covert. Therefore, only Christian slaves understood them, and even when ordinary words were used, they reflected personal relationship between the slave singer and God.

The codes of the first negro spirituals are often related with an escape to a free country. For example, a "home" is a safe place where everyone can live free. So, a "home" can mean Heaven, but it covertly means a sweet and free country, a haven for slaves. The ways used by fugitives running to a free country were riding a "chariot or a "train". The negro spirituals "The Gospel Train" and "Swing low, sweet chariot" which directly refer to the Underground Railroad, an informal organization who helped many slaves to flee.

The lyrics of "The Gospel train" are "She is coming... Get onboard... There's room for many more..." This is a direct call to go way, by riding a "train" which stops at "stations". Then, "Swing low, sweet chariot" refers to Ripley, a "station" of the Underground Railroad, where fugitive slaves were welcome. This town is atop a hill, by Ohio River, which is not easy to cross. So, to reach this place, fugitives had to wait for help coming from the hill. The words of this spirituals say, "I looked over Jordan and what did I see/ Coming for to carry me home/ A band of angels coming after me".

Spirituals were sung at churches with an active participation of the congregation (as it is usual in a Pentecostal church). Their lyrics mainly remain similar to those of the first negro spirituals. They were often embellished and they were also called either "church songs" or "jubilees" or "holy roller songs". But some hymns were changed by African American and became "Dr Watts".

The particular feature of this kind of singing was its surging, melismatic melody, punctuated after each praise by the leader's intoning of the next line of the hymn. The male voices doubled the female voices an octave below and with the thirds and the fifths occurring when individuals left the melody to sing in a more comfortable range. The quality of the singing was distinctive for its hard, full-throated and/or nasal tones with frequent exploitation of falsetto, growling, and moaning.

The beats of Dr Watt's songs were slow, while there are other types of spirituals. These beats are usually classed in three groups:

- the "call and response chant", - the slow, sustained, long-phrase melody, - and the syncopated, segmented melody, - "Call and response"

For a "call and response chant", the preacher (leader) sings one verse and the congregation (chorus) answers him with another verse. An example of such songs is "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot"

As traditional negro spirituals continued to be sung, new Gospel songs were created. The lyrics of these new songs dealt with praising the Lord, with personal improvement and with brotherly community life. Many of them were inspired by social problems: segregation, lack of love, drugs, etc. For the struggle for Civil Rights, in the 1960s, negro spirituals like "We shall overcome", "Oh Freedom" and "This Little Light of Mine" used to be sung.

Sometimes the words of traditional negro spirituals were slightly changed and adapted to special events. For example, the words of "Joshua Fought the Battle of Jericho (and the walls came tumbling down)" were changed into "Marching 'round Selma". During this period, some Gospel songs were more secular. They were included in shows like "Tambourine to Glory" (by Langston Hughes). In the 1970s, mainly Edwin Hawkins ("Oh Happy Day") created the "pop-gospel"». This type of singing needs several instruments to accompany the singers who are often assembled in choirs.

Between 1925 and 1985, negro spirituals were sung in local communities. Some scientists, such as Alan Lomax and John Lomax, collected them, as they were spontaneous performed. At the same time, composers, such as John W. Work, arranged their tunes. Some of these composers , such as Jester Hairston, were influenced by the Black Renaissance. This means that their arrangements were influenced by the European classic music. After 1925, artists created Gospel songs, which were either "soul" or "hard beat". The number of instruments accompanying singers increased. Some composers, such as Moses Hogan, arranged traditional negro spirituals.

The new Gospel songs created after 1985 are of two types. The first type concerns songs, which are for either worship services or special events in churches. The second type includes songs, which are for concerts. They are more or less secular even when they speak of Christian life. --- negrospirituals.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega mediafire zalivalka cloudmailru uplea