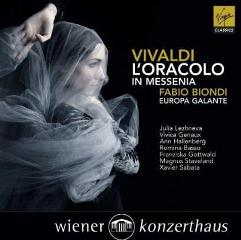

Vivaldi – L’Oracolo in Messenia (Wien 2012)

Vivaldi – L’Oracolo in Messenia (Wien 2012)

1. Part I 2. Part II 3. Part III Broascast of Programme 2 on Polish Radio Cast: Polifonte, king of Messenia - Magnus Staveland, tenor Merope, queen of Messenia, widow of Cresfonte - Ann Hallenberg, mezzo-soprano Epitide, son of Merope, disguised under the name of Cleon - Vivica Genaux, mezzo soprano Elmira, princess of Etolia - Romina Basso, mezzo-soprano Trasimede, chief minister of Messenia - Julia Lezhneva, soprano Licisco, ambassador from Etolia - Franziska Gottwald, mezzo-soprano Anassandro, confidant of Polifonte - Xavier Sabata, countertenor Europa Galante (three violins, viola, cello, double bass, oboe, bassoon, horn, theorbo, and harpsichord) Fabio Biondi – conductor

This recording is an admirable work. The score for Vivaldi's opera L'Oracolo in Messenia is lost. The libretto, however, survived, and Fabio Biondi reconstructed the opera as a pastiche, transplanting onto the words music from Giacomelli's opera La Merope, which is clever because there are hints that Vivaldi did just that, since his L'Oracolo in Messenia was a readaptation of Giacomelli's La Merope and may have had music directly borrowed from it - it was actually a pastiche as well. This practice of borrowing arias from other composers wasn't uncommon at the time, and there are numerous other examples of such in Vivaldi's works. Fabio Biondi also used music from Vivaldi's own operas, including Griselda, Catone in Utica, Motezuma, Dorilla in Tempe, Farnace (Ferrara version), and Semiramide. Two outstanding additional numbers come from Broschi's Artaserse, and Hasse's Siroe, re di Persia.

Vivaldi wrote a first version of this opera for Venice (in very short notice, to savage his season after his Siroe, re di Persia fell apart in Ferrara thanks to the archbishop refusing to allow the composer into the city due to suspecting him of sinful relations with the singer Anna Girò), and it was greatly successful. The score for it is lost. It was received with "tumultuous applause" and "firm approval" according to the papers. In need for something guaranteed to be successful thanks to the financial difficulties brought about by the Ferrara fiasco, Vivaldi relied on Giacomelli's La Merope, given that it was a smashing triumph (in part, thanks to the casting of the two best castrati in town, Farinelli and Caffarelli).

When Vivaldi decided to quit Venice (the circumstances are well explained in the insert) and move to Vienna, he thought he should take this particular opera with him, due to the fact that Zeno, the librettist, was a former poet laureate to the imperial court in Vienna. Besides, this was arguably Zeno's best libretto, described by the poet as "the least bad of my dramas." Vivaldi wanted to make an even better impression, and added three ballets and seven new arias, dropping three of the old ones (Fabio Biondi does conserve one of them - "S'in campo armato" - which only existed in the Venetian version). He also changed the name of one character - the princess Argia became Elmira.

Vivaldi evidently hoped for the same success achieved in Venice for his Viennese version, since he wanted to impress the emperor. But fate decided otherwise: on 20 October 1740, before Vivaldi's premiere, Charles VI suddenly died, allegedly after eating poisonous mushrooms. All theaters in Vienna were closed down for one year, in sign of grieving for the emperor. Vivaldi made unsuccessful attempts to obtain a commission from the emperor's successor (Prince Anton Ulrich von Saxe-Meiningen). Without a sponsor, the composer plunged into financial turmoil, sold his scores at rock-bottom prices, and died himself shortly thereafter, receiving a pauper's funeral.

Still, after the theaters reopened, Vivaldi's L'Oracolo in Messenia, Viennese version, did see the light of day. Apparently Prince Anton was remorseful for having brushed off Vivaldi, and Anna Girò, Vivaldi's loyal friend, also insisted that the opera should be staged (she sang the role of Merope). This posthumous production allowed the Viennese public to hear a moving postscript to the great composer's operatic career. And now, Fabio Biondi brings us what is likely to be a rather close approximation, because while the score for the second version is also lost, in the surviving libretto Vivaldi did give indications of what music he was planning to borrow for his pastiche. --- Almaviva, amazon.com

download: