Shostakovich - Symphony No. 5 in D Minor

| Classical Notes |

Shostakovich - Symphony No. 5 in D Minor

On the eve of Jan. 26, 1936 Joseph Stalin and his entourage attended a performance of Shostakovich's “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District” but they left the theater before the last act. The opera had been playing to acclaim for two years in Moscow and its 29-year-old composer was hailed a Russian musical genius, beloved by his fellow countrymen.

Shostakovich - Symphony No. 5 in D Minor

A few days after Stalin's ominous attendance, a vociferous and damning editorial called "Muddle Instead of Music" appeared anonymously in “Pravda,” the official Communist Party newspaper. The editorial denounced Shostakovich as a "formalist" and petty bourgeois composer whose "intentionally unharmonious muddled flow of sounds" was a danger to the Soviet people.

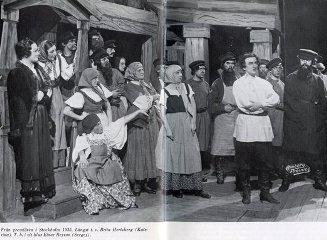

Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk - premiere, poster 1934

The next morning the state newspaper “Pravda” condemned the work, saying it corrupted the Soviet spirit. The opera disappeared overnight and every publication and political organization in the country heaped personal attacks on its composer. This was no small matter; most who drew the dictator's wrath soon died in a labor camp. Shostakovich lived in fear, sleeping in the stairwell outside his apartment to spare his family the experience of his imminent arrest.

Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk - Stockholm 1935

Shostakovich was luckier, perhaps because the young composer had already achieved some international recognition, but the attacks in “Pravda” turned him into a pariah who began keeping a packed suitcase beside his bed in case he were arrested in the night.

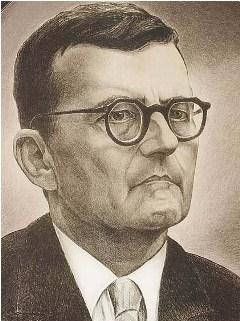

Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich's next misstep came with the Fourth Symphony, which he had been composing in his mind for some time. Despite the risk of associating with an “enemy of the people,” Evegeny Mravinsky (conductor) and the Leningrad Philharmonic agreed to premiere it, but the rehearsals went badly, and it became clear to Shostakovich that a performance of such a forward-looking work would be dangerous to his life. In December of 1936, he announced that it was a failure and withdrew it, ostensibly to work on the finale. The Fourth was lost during the war, and it was only in 1961 that it was reconstructed and premiered exactly as written.

Dmitri Shostakovich

In such an atmosphere, and with a wife and two young children to worry about, it was only natural that Shostakovich would pull his head back into his shell and try to please the authorities. And so he did, at least on the surface: the Fifth Symphony's subtitle is ``A Soviet Artist's Practical Creative Reply to Just Criticism.''

Dmitri Shostakovich

Meanwhile, Stalin and his officials awaited the debut of his Fifth Symphony to see if a chastened Shostakovich had "reformed" and written music according to their dictates.

Joseph Stalin and his entourage

Against this backdrop of pervasive political terror and personal attack, Shostakovich had to find a way to write his Symphony No. 5, scheduled to premiere Nov. 21, 1937. Fearing arrest, torture and even death, the composer, with sly brilliance and a remarkable spirit, found a way to compose music which appeared to adhere to Stalin's directives while subtly weaving a deeper and sardonic musical truth, bearing testimony to the despair and terror that reigned over the nation.

Evgeny Mravinsky & Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich slimmed down his musical style considerably from the superabundance of the Fourth, with less orchestral color and a smaller breadth of scope. With this scaling down also came a refinement of his pithiness and a deepening of ambiguity. More importantly, Shostakovich found a language through which he could speak with power and eloquence over the following three decades. It is the power to weld an audience together, uplifting and moving them in a single emotion-controlled wave, sweeping aside all intellectual reservations.

Dmitri Shostakovich

The Symphony quotes Shostakovich's song “Vozrozhdenije” (Op. 46 No. 1, composed in 1936–37), most notably in the last movement, which uses a poem by Alexander Pushkin that deals with the matter of rebirth. This song is by some considered to be a vital clue to the interpretation and understanding of the whole symphony. In addition, commentators have noted that Shostakovich incorporated a motif from the "Habanera" from Bizet's Carmen into the first movement, a reference to Shostakovich's earlier infatuation with a woman who refused his offer of marriage, and subsequently moved to Spain and married a man named Roman Carmen.

Shostakovich - Symphony No.5, cond. Mravinsky

The first movement begins with a cry of despair, a tragic lament that goes on for some time before suddenly being interrupted by a goose-stepping march led by a two-note tympani theme, a motive that musicologist Ian MacDonald calls the “Stalin theme.”' The third movement is one of the most despairing pieces of music ever written, a memorial for Mother Russia and all those sent to the labor camps. And of the finale, Shostakovich wrote in his memoirs (smuggled out of Russia after the composer's death):

“ What exultation could there be? I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat... It's as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying ``Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,'' and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ``Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.'' What kind of apotheosis is that? You have to be a complete oaf not to hear that.”

Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5 reflected his situation as an artist who would be judged by politics as much as by talent. Although some audiences heard condemnation of the government through inflections of despair, Stalin found the politics of the music acceptable and Shostakovich won a reprieve – at least for another decade.

Shostakovich - Symphony No.5, score (beginning)

The Fifth was hugely successful. The government was pleased that the rebel had knuckled under, while the Russian in the street saw the truth behind the facade. Western listeners, generally unaware of what was going on behind Stalin's mask, took the work at face value, yet were still overwhelmed by its grandeur and beauty. The symphony has become Shostakovich's most popular work, and the relatively recent revelation of its true meaning can only enhance our enjoyment of this testament to one man's struggle to express his people's anguish under a brutal tyrant.

Dmitri Shostakovich